WITH Nero the line of the Caesars became extinct. Among the many prophetic indications of this event two outstanding ones, are mentioned by historians. As Livia was returning to her home at Veii after marrying Augustus [38 B.C.], an eagle flew by and dropped into her lap a white pullet which it had just pounced upon. Noticing a laurel twig in its beak she decided to keep the pullet for breeding and to plant the twig. Soon the pullet raised such a brood of chickens that the house is still known as 'The Poultry'; moreover the twig took root and grew so luxuriously that the Caesars always plucked laurels from it to wear at their triumphs. It also became an imperial custom to cut new slips and plant these close by. Remarkably enough, the death of each Emperor was anticipated by the premonitory wilting of his laurel; and in the last year of Nero's reign not only did every tree wither at the root, but the whole flock of poultry died. And, as if that were insufficient warning, a thunderbolt presently struck the Temple of the Caesars, decapitated all the statues at a stroke and dashed Augustus's sceptre from his hands.

2. Galba succeeded Nero. Though not directly related to the Julians, he came from a very ancient aristocratic house, and used to amplify the inscriptions on his own statues with the statement that Quintus Catulus Capitolinus was his great-grandfather; and even had a tablet set up in the Palace forecourt, tracing his ancestry back to Jupiter on the male, and to Pasiphaë, Minos's wife, on the female side.

3. It would be tiresome to reproduce this pedigree here in all its glory; but I shall touch briefly on Galba's immediate family. Why the surname 'Galba' was first assumed by a Sulpician, and where it originated, must remain moot points. One suggestion is that after a tediously protracted siege of some Spanish town the Sulpicius in question set fire to it, using torches smeared with resin (galbanum). Another is that he resorted to galbeum, a kind of poultice, during a long illness. Others are that he was very fat, the Gallic word for which is galba; or that, on the contrary, he was very small — like the galba, a creature which breeds in oak trees. The Sulpicians acquired a certain lustre during the consulship of Servius Galba, described as the most eloquent speaker of his time, and preserve a tradition that, while governing Spain as pro-Praetor, he massacred 30,000 Lusitanians — an act which provoked the war with Viriathus. Servius Galba's grandson, enraged when Julius Caesar, whose lieutenant he had been in Gaul, passed him over for the consulship, joined the assassins Brutus and Cassius, and was subsequently sentenced to death under the Pedian Law. The Emperor Galba's father and grandfather were descended from this personage. The grandfather had a far higher reputation as a scholar than as a statesman, never rising above the rank of praetor but publishing a monumental, and not negligible, historical work. The father, however, won a consulship; and although so squat as to be almost a hunch-back, and a poor speaker into the bargain, he proved indefatigable in public business. He married, first Mummia Achaica, grand-daughter of Catulus and great-grand-daughter of the Lucius Mummius who sacked Corinth; and then Livia Ocellina, a rich and beautiful woman, whose affections are said to have originally been stirred by his rank, but afterwards even more by his frankness — in reply to her bold advances he furtively stripped to the waist and revealed his hump as a proof that he wished to hide nothing from her. Achaica bore him two sons: Gaius and Servius. Gaius, the elder, left Rome owing to financial embarrassment; and, because Tiberius crossed him off the list of proconsuls, when he became due for a province, committed suicide.

4. On 24 December 3 B.C., while Messala and Lentulus were Consuls, Servius Galba, the Emperor-to-be, was born in a hillside house beside the road which links Terracina with Fundi. To please his stepmother Livia Ocellina, who had adopted him, he took the name Livius, the surname Ocellus, and even the forename Lucius, until becoming Emperor. According to some writers Augustus once singled Galba out from a group of small boys and chucked him under the chin, saying in Greek: 'You too will taste a little of my glory, child'; and Tiberius, hearing that he would be Emperor when an old man, grunted:

'Very well, let him live in peace; the news does not concern me in the least.'

One day, as Galba's grandfather was invoking sacrificial lightning, an eagle suddenly snatched the victim's intestines out of his hands and carried them off to an oak-tree laden with acorns. A bystander suggested that this sign portended great honour for the family. 'Yes, yes, perhaps so,' the old man agreed, smiling, 'on the day that a mule foals.' When Galba later launched his rebellion, what encouraged him most was the news that a mule had, in fact, foaled. Although everyone else considered this a disastrous omen, Galba remembered the sacrifice and his grandfather's quip, and interpreted it in precisely the opposite sense.

He had already dreamed that the Goddess Fortune visited him to announce that she was tired of waiting outside his door and would he please let her in quickly or she would be fair game for the next passer-by. He awoke, opened the door, and found on the, landing a bronze image of the Goddess, more than a cubit tall. This he carried lovingly to Tusculum, his summer home, and consecrated a private chapel to Fortune; worshipping her with monthly sacrifices and an annual vigil.

Even as a young man he faithfully observed the national custom, already obsolescent, of summoning his household slaves twice a day to wish him good-morning and good-night, one after the other.

5. Galba was a conscientious student of public affairs, and particularly skilled in law. He took marriage seriously but, on losing his wife Livia and the two sons she had borne him, remained single for the rest of his life. Nobody could interest him in a second match, not even Agrippina who, when her husband Domitius died, made such shameless advances to him — though he had not yet become a widower — that his mother-in-law gave her a public reprimand, going so far as to slap her in front of a whole bevy of married women.

Galba always behaved most graciously to Livia Augusta, who showed him considerable favour while she lived, and then left him half a million gold pieces, the largest bequest of all. But, because the amount was expressed in figures, not words, Tiberius, as her executor, reduced it to a mere 5,000; and Galba never handled even that modest sum.

6. He won his first public appointment while still under age. As praetor in charge of the Floral Games he introduced the spectacular novelty of tightrope-walking elephants. Then he governed the province of Aquitania for nearly a year, and next held a consulship for six months. Curiously enough, Galba succeeded Nero's father, Gnaeus Domitius, and preceded Salvius Otho, father of Otho — a foreshadowing of the time when he should reign between these two Consuls' sons. At Caligula's orders Galba replaced Gaetulicus as Governor-general of Greater Germany. The day after taking up his command he put a stop to manual applause at a religious festival, by posting a notice to the effect that 'hands will be kept inside uniform cloaks on all occasions.' Very soon the following doggerel went the rounds:

Soldier, soldier, on parade,

You should learn the soldier's trade,

Galba's now commanding us —

Galba, not Gaetulicus!

Galba came down just as severely on requests for leave. In gruelling manoeuvres he toughened old campaigners as well as raw recruits, and sharply checked a barbarian raid into Gaul. Altogether, he and. his army made so favourable an impression when Caligula came to inspect them, that they won more praise and prize money than any other troops in the field. Galba scored a personal success by doubling for twenty miles, shield on shoulder, beside the Emperor's chariot, while continuing to direct manoeuvres.

7. Although strongly urged to proclaim himself Emperor after Caligula's murder, Galba held back, thus earning Claudius's heartfelt gratitude. Claudius, indeed, considered Galba so close a friend that,. when a slight indisposition overtook him, the British expedition was postponed on his account. Later, Galba became proconsul in Africa for two years, with instructions to suppress the disturbance caused there by domestic rivalries and a native revolt. He executed his commission somewhat ruthlessly, it is true, but showed scrupulous attention to justice. Discovering, for instance, that while rations were short, a certain legionary had sold a peck of surplus wheat for a gold piece, he forbade all ranks to feed the fellow when his stores were exhausted; and let him starve to death. At a court of inquiry into the ownership of a transport animal, Galba found both the evidence and the pleadings unsatisfactory and, since the truth seemed to be anybody's guess, gave orders:

'Lead the beast blindfold to its usual trough and let it drink. Then uncover its eyes and watch to whom it goes of its own accord. That man will be the owner.'

8. For these achievements in Africa and his previous successes in Germany, Galba won triumphal decorations and a triple priesthood, and was elected both to the Fellowship of the Fifteen, and to the Titian and Augustan Guilds. But from then onwards, until the middle years of Nero's reign, he lived almost exclusively in retirement, never going anywhere, even for a country drive, without the escort of a second carriage containing 10,000 gold pieces. At last, while living at Fundi, he was offered the governorship of Tarragonian Spain; where, soon after his arrival, as he sacrificed in a temple, the incense-carrying acolyte went white-haired before his eyes — a sign shrewdly read as portending the succession of a young Emperor by an old one. And presently, when a thunderbolt struck a Cantabrian lake, twelve axes, unmistakable emblems of high authority, were recovered from it.

9. He ruled Tarragonian Spain for eight years, beginning with great enthusiasm and energy, and even going a little too far in his punishment of crime. He sentenced a money-changer of questionable honesty to have both hands cut off and nailed to the counter; and crucified a man who had poisoned his ward to inherit the property. When this murderer begged for justice, protesting that he was a Roman citizen, Galba recognized his status and ironically consoled him with:

'Let this citizen hang higher than the rest, and have his cross whitewashed.'

As time wore on, however, he grew lazy and inactive; but this was done purposely to deny Nero any pretext for disciplining him. In his own words:

'Nobody can be forced to give an account of how he spends his leisure hours.'

Galba was holding assizes at New Carthage when news reached him of the revolt in Celtic Gaul. It came in the form of an appeal for help sent by the Roman Governor-general of Aquitaine, which was followed by another from Gaius Julius Vindex asking, would he take the lead in rescuing humanity from Nero? He accepted the suggestion, half hopefully, half fearfully, but without much delay, having accidentally come across Nero's secret orders for his own assassination; and took heart from certain very favourable signs and portents especially the predictions of a nobly-born girl which (according to Jupiter's priest at Clunia) matched the prophecies spoken in a trance by another girl two centuries before — the priest had just found a record of these in the Temple vault, following directions given him in a dream. The gist of these prophecies was that the lord and master of the world would some day arise in Spain.

10. Accordingly, Galba took his place on the Tribunal, as though going about the business of freeing slaves, but before him were ranged statues and pictures of Nero's prominent victims. A young aristocrat, recalled from exile in the near-by Balearic Islands for this occasion, stood near while Galba deplored the present state of the Empire. Galba was at once hailed as Commander-in-Chief, and accepted the honour; announcing that he would now govern all Spain in the name of the Roman Senate and people. He closed the courts, and began raising regular troops and militia from the native population to increase his existing command of one legion, two squadrons of cavalry, and three unattached infantry battalions. Next, he chose the most distinguished and intelligent Spaniards available as members of a provincial senate, to which matters of State importance could always be referred. He also picked certain young knights, instead of ordinary troops to guard his sleeping quarters, and although these ranked as volunteer infantrymen they still wore the gold rings proper to their condition. Then he called upon all Spanish provincials to unite energetically in the common cause of rebellion. At about this time a ring of ancient design was discovered in the fortifications of the city that he had chosen as his headquarters; the engraved gem represented Victory raising a trophy. Soon afterwards an Alexandrian ship drifted into Tortosa, loaded with arms, but neither helmsman, crew, nor passengers were found aboard her — which left no doubt in anyone's mind that this must be a just and righteous war, favoured by the gods.

Suddenly, however, without the least warning, Galba's rebellion nearly collapsed. As he approached the station where one of his cavalry troops was quartered, the men felt a little ashamed of their defection and tried to go back on it; Galba kept them at their posts only by a great effort. Again, he was nearly murdered on his way to the baths: he had to pass down a narrow corridor lined by a company of slaves whom an Imperial freedman had presented to him — obviously with some treachery in view. But while they plucked up their courage by urging one another 'not to miss this opportunity', someone took the trouble to ask: 'What opportunity?' Later they confessed under torture.

11. Galba's embarrassments were increased by the death of Vindex, a blow so heavy that it almost turned him to despair and suicide. Presently, however, messengers arrived from Rome with the news that Nero, too, was dead, and that the citizens had all sworn obedience to himself; so he dropped the title of Governor-general and assumed that of Caesar. He now wore an imperial cloak, with a dagger hanging from his neck, and did not put on a gown again until he had accounted first for Nymphidius Sabinus, Commander of the City Guards, and then for Fonteius Capito and Clodius Macer, who commanded respectively in Germany and Africa, and were plotting further trouble.

12. Stories of Galba's cruelty and greed preceded him; he was said to have punished townships that had been slow to receive him by levying huge taxes and even dismantling their fortifications; to have executed not only local officials and administrators, but their families too; and, when the Tarragonians offered him a golden crown from the ancient Temple of Jupiter described as weighing 15lb, to have melted this down and made them supply the three ounces needed to tip the scales at the advertised weight. Galba more than confirmed this reputation on his entry into Rome. He sent back to rowing duty some sailors whom Nero had turned into marines; and when they stubbornly insisted on their right to the Imperial Eagle and appropriate badges, ordered his cavalry to charge them; then had them lined up against a wall, and every tenth man cut down. Galba also disbanded Nero's German guards, who had served several previous emperors and proved consistently loyal; repatriating them without a bounty on the grounds that they had shown excessive devotion to Dolabella by camping close to his estate. Other anecdotes to his discredit, possibly true, possibly false, went the rounds: when an especially lavish dinner was set before him he had groaned aloud; when presented with the usual abstract of Treasury accounts, he had rewarded the Treasurer's scrupulous labours with a bowlful of beans; and, delighted by Canus's performance on the flute, he had drawn the magnificent sum of five denarii from his purse and pressed them on him.

13. Galba's accession was not entirely popular, as became obvious at the first theatrical show he attended. This was an Atellan farce, in which occurred the well-known song 'Here comes Onesimus, down from the farm...' The whole audience took up the chorus with fervour, repeating that particular line over and over again.

14. His power and prestige were far greater while he was assuming control of the Empire than, afterwards: though affording ample proof of his capacity to rule, he won less praise for his good acts than blame for his mistakes. Three Palace officials, nicknamed 'the Imperial nurse-maids', always hovered around Galba; he seemed to be tied to their apron-strings. These were the greedy Titus Vinius, his late superior in Spain; the intolerably arrogant and stupid Cornelius Laco, an ex-assessor and Commander of the Guards; and his own freedman Icelus who, having recently acquired the surname of Marcianus and the right to wear a gold ring, now had his eye on the highest appointment available to a man of his rank, namely Laco's. Galba let himself be so continuously guided by these experts in vice that he was far less consistent in his behaviour — at one time meaner and more bitter, at another more wasteful and indulgent — than an elected leader had any right to be in the circumstances.

He sentenced men of all ranks to death without trial on the scantiest evidence, and seldom granted applications for Roman citizenship. Nor would he concede the prerogatives which could, in law, be enjoyed by every father of three children, except to an occasional claimant; and then for a limited period only. When the judges recommended the formation of a sixth judicial division, Galba was not content simply to turn this down, but cancelled the privilege, which Claudius had allowed them, of being excused court duties in the winter months or during the April New Year celebrations.

15. It was generally believed that he intended to restrict all official appointment, both for knights and senators, to two-year periods, and choose only men who either did not want them or could be counted on to refuse. He annulled all Nero's awards, letting the beneficiaries keep no more than a tenth part, enlisting the help of fifty knights to ensure that his order was obeyed, and ruling that if any actor or other performer had sold one of Nero's gifts, spent the money, and was unable to refund it, the missing sum must be recovered from the buyers. Yet he denied his friends and freedmen nothing, with or without payment — immunity from taxes, an innocent party sentenced here, a culprit excused there. Moreover, when a popular demand arose for the punishment of Halotus and Tigellinus, undoubtedly the vilest of all Nero's assistants, Galba not only protected their lives but gave Halotus a lucrative post and published an imperial edict charging the people with undeserved hostility towards Tigellinus.

16. Thus he outraged all classes at Rome; but the most virulent hatred of him smouldered in the Army. Though a larger bonus than usual had been promised soldiers who had pledged their swords to Galba before his arrival in the City, he would not honour this commitment, but announced: 'It is my custom to levy troops, not to buy them.' This remark infuriated the troops everywhere; and he earned the Guards' particular resentment by his dismissal of a number of them suspected of being in Nymphidius's pay. The loudest grumbling came from camps in Greater Germany, where the men claimed that they had not been rewarded for their share in Virginius Rufus's operations against Vindex. These, the first Roman troops bold enough to withhold their allegiance, refused on January 1st to take any oath except in the name of the Senate; informing the Guards, by messenger, that they were thoroughly at odds with this Spanish appointed Emperor, and would the Guards please choose one who deserved the approval of the Army as a whole?

17. Galba heard about this message and, thinking that he was being criticized for his childlessness rather than his senility, singled out from a group of his courtiers a handsome and well-bred young man, Piso Frugi Lucianus, to whom he had already shown great favour, and appointed him perpetual heir to his name and property. Calling him 'my son', he led Piso into the Guards' camp, and there formally and publicly adopted him — without, however, mentioning the word 'bounty', and thus giving Otho an excellent opportunity for his coup d'etat five days later.

18. A succession of signs had been portending Galba's end in accurate detail. During his march on Rome people were being slaughtered right and left whenever he passed through a town; and once an ill-timed axe blow made a frenzied ox break its harness and charge Galba's chariot, rearing up and drenching him with blood. Then, as he climbed out, one of his runners, pushed by the mob, nearly wounded him with a spear. When Galba first entered the City, and again when he took over the Palace, a slight earthquake shock was felt, and a sound arose as of bulls bellowing. Clearer presages followed. Galba had set aside from his treasures a pearl-mounted collar and certain other jewels, which were to decorate the Goddess Fortune's shrine at Tusculum. But, impulsively deciding that they were too good for her, he consecrated them to Capitoline Venus instead. The very next night Fortune complained to him in a dream that she had been robbed of a gift intended for herself, and threatened to take back what she had already given him. At dawn, Galba hurried in terror towards Tusculum to expiate the fault revealed by his dream, having sent outriders ahead to prepare sacrifices; but when he arrived, found only warm ashes on the altar and an old black-cloaked fellow offering incense in a glass bowl, and wine in an earthenware cup — whereas decency called for a white-robed boy with a chalice and thurible of precious metal. It was noticed, too, that while he was sacrificing on the Kalends of January his garland fell off, and that the sacred chickens flew away when he went to read the auspices. Again, before Galba addressed the troops on the subject of Piso's adoption, his aide forgot to set a camp chair on the Tribunal; and in the Senate House his curule seat was discovered to be facing the wall.

19.When attending an early morning sacrifice, Galba was now repeatedly warned by a soothsayer to expect danger — murderers were about. Soon afterwards news came that Otho had seized the Guards' camp. Though urged to hurry there in person, because his rank and presence could carry the day, Galba stayed where he was, bent on rallying to his standard the legionaries scattered throughout the City. He did, indeed, put on a linen corselet, but remarked that it would afford small protection against so many swords. Meanwhile, some of his supporters rashly assured him that peace had been made and the rebels arrested — their troops were on the way to surrender and pledge loyal allegiance. Completely deceived, Galba went forward to meet them in the utmost confidence. When a soldier claimed with pride to have killed Otho, he snapped: 'On whose authority?' and hurried on to the Forum. There a party of cavalrymen, clattering through the City streets and dispersing the mob, recognized him. These were his appointed assassins. They reined in for a moment, then charged at the solitary figure and cut him down.

20. Just before his death Galba is said to have shouted out: 'What is all this, comrades? I am yours, you are mute!' and gone so far as to promise the bounty; but, according to the more usual account, he realized the soldiers' intention, bared his neck and encouraged them to kill him. Oddly enough, no one present made any attempt at rescue, and all the Guards summoned to rally around him turned a deaf ear. A single company of Germans alone rushed to his assistance because he had once treated them with kindness while they were convalescents; not knowing the City well, however, they took a wrong turning, and arrived too late.

Galba was murdered beside the Cutian pool, and left lying just as he fell. A private soldier returning from the grain issue set down his load and decapitated Galba's body. He could not carry the head by the hair — this will be explained shortly — but stuffed it in his cloak; and presently brought it to Otho with his thumb thrust into the mouth. Otho handed the trophy to a crowd of servants and camp-boys, who stuck it on a spear and carried it scornfully round the camp. chanting at intervals:

'Galba, Galba, Cupid Galba,

Please enjoy your vigour still!'

Apparently Galba had enraged them by quoting Homer to someone who congratulated him on his robust appearance:

So far my vigour undiminished is.

A former freedman of Patrobius Neronianus bought the head for 100 gold pieces, but only to hurl it to the ground exactly where Patrobius had been murdered at Galba's orders. In the end the Imperial steward Argivus removed it, with the trunk, to the tomb in Galba's private gardens which lay beside the Aurelian Way.

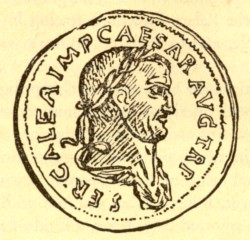

21. The following is a physical account of Servius Sulpicius Galba:

| Height: | medium |

|---|---|

| Hair: | none |

| Eyes: | blue |

| Nose: | hooked |

| Hands and Feet: | twisted by arthritis or some such disease, which made him unable to manage parchment scrolls or wear shoes. |

| Body: | badly ruptured on the right side, requiring a truss for support. |

He was a heavy eater, in winter always break-fasting before daylight; and with a habit, at dinner, of passing on accumulated leavings to his attendants. A homosexual invert, he showed a decided preference for mature, sturdy men. It is said that when Icelus, one of his trusty bed-fellows, brought the news of Nero's death, Galba showered him with kisses and begged him to undress without delay; whereupon intimacy took place.

22. Galba died at the age of seventy-three, before he had reigned seven months. The Senate at once voted that a column decorated with ships' beaks should be set up in the Forum to accommodate his statue and mark the spot where he had fallen. Vespasian, however, subsequently vetoed this decree; he was convinced that Galba had sent agents from Spain to Judaea with orders for his assassination.