THE seat of Otho's ancient and distinguished family was the city of Ferentium; they could trace their origins back to an Etruscan royal house. His grandfather, Marcus Salvius Otho, the son of a Roman knight and a peasant girl — she may not even have been free-born — owed his place in the Senate, where he never rose above praetor's rank, to the influence of his protectress Livia Augusta. He made a brilliant marriage; but his son, Lucius Otho, was generally supposed to be a bastard of his patron Tiberius, whom he closely resembled. This Lucius (father of the Emperor) had the reputation of being a strict disciplinarian, whether during his magistracies at Rome or his proconsulship in Africa, or when on special military missions. In Illyricum he went so far as to preside over the execution of those soldiers who, repenting of having been led by their officers to join Camillus's rebellion, killed them; though he knew well enough that the Emperor Claudius himself had rewarded these same men with promotion for the act. Lucius Otho's rough justice may have preserved his reputation, yet it certainly put him out of favour at Court until, by extorting information from a group of slaves, he contrived to uncover a plot against the Emperor's life. Thereupon the Senate paid Lucius the unique honour of setting up his statue in the Palace; and Claudius, in raising him to patrician rank, is said to have panegyrized him as 'one whose loyalty I can hardly dare hope that my children will emulate.' Alba Terentia, his nobly-born wife, bore him two sons: the elder named Lucius Titanius, and the younger Marcus Otho, like his grandfather; also a daughter, who was betrothed in her girlhood to Germanicus's son Drusus.

2. Otho, the Emperor-to-be, was born on 25 April 32 A.D. while Camillus Arruntius and Domitius Ahenobarbus were Consuls. His early wildness earned him many a beating from his father; he is said to have been in the habit of wandering about the City at night and tossing in a blanket any drunk or disabled person who crossed his path. After his father's death he advanced his fortunes by a pretended passion for an influential freedwoman at Court, though she was almost on her last legs; with her help he insinuated himself into the position of Nero's leading favourite. This may have happened naturally enough, since Nero and Otho were birds of a feather, yet it has quite often been suggested that their relationship was decidedly unnatural. Be that as it may, Otho grew so powerful that he did not think twice before bringing one of his own protégés, a Consul found guilty of extortion, back into the Senate House, and there thanking the Senators in anticipation for the pardon that they were to grant him, having accepted an immense bribe.

3. As Nero's confidant he had a finger in all his schemes, and on the day chosen by the Emperor for murdering his own mother, threw everyone off the scent by inviting them both to an exceptionally elegant luncheon party. Otho was asked to become the protector of Poppaea Sabina — who had been taken by Nero from her husband to be his mistress — and they went through a form of marriage together. However, he not only enjoyed Poppaea, but conceived so deep a passion for her that he would not tolerate even Nero as a rival; we have every reason to believe the story of his rebuffing, first, the messengers sent by Nero to fetch Poppaea, and then Nero himself, who was left on the wrong side of the bedroom door, alternately threatening and pleading for his rights in the lady. Fear of scandal alone kept Nero from doing more than annul the marriage and banish Otho to Lusitania as its Governor-general. So the following lampoon went the rounds:

Otho in exile? 'Yes and no';

That is, we do not call it so.

And may we ask the reason why?

They charged him with adultery.

But could they prove it?

'No and yes': It was his wife he dared caress.

4. Otho, who held the rank of quaestor, governed Lusitania for ten years with considerable restraint, and seized the earliest opportunity of revenging himself on Nero by joining Galba as soon as he heard of the revolt; but the political atmosphere was so uncertain that he did not underrate his own chances of sovereignty. Seleucus, an astronomer who encouraged these ambitions, had already foretold that Otho would outlive Nero, and now arrived unexpectedly with the further prediction that he would soon also become Emperor. After this Otho missed no chance of flattering or showing favour to anyone who might prove useful to him. When he entertained Galba at dinner, for instance, he would bribe the bodyguard with gold and do everything possible to put the rest of the Imperial escort in his debt. Once a friend of Otho's laid claim to part of a neighbour's estate, and asked him to act as arbitrator; Otho bought the disputed piece of land himself and presented it to him. No one at Rome questioned his fitness to wear the imperial purple, and it was openly said that he could hardly avoid doing so.

5. Galba's adoption of Piso came as a shock to Otho, who had hoped to secure this good fortune himself. Disappointment, resentment and a massive accumulation of debts now prompted him to revolt. His one chance of survival, Otho frankly admitted, lay in becoming Emperor. He added:

'I might as well fall to some enemy in battle as to my creditors in the Forum.'

The 10,000 gold pieces, just paid him for a stewardship by one of the Emperor's slaves, served to finance the undertaking. To begin with he confided in five of his personal guards, each of whom co-opted two others; they were paid 100 gold pieces a head and promised fifty more. These fifteen men recruited a certain number of assistants, but not many, since Otho counted on mass support as soon as he had raised the standard of revolt.

6. His first plan was to occupy the Guards' Camp immediately after Piso's adoption, and to capture Galba during dinner at the Palace. But he abandoned this because the same battalion happened to be on guard duty as when Gaius Caligula had been assassinated, and again when Nero had been left to his fate; he felt reluctant to deal their reputation for loyalty a further blow. Unfavourable omens, and Seleucus's warnings, delayed matters another five days. However, on the morning of the sixth, Otho posted his fellow-conspirators in the Forum at the gilt milestone near the Temple of Saturn while he entered the Palace to greet Galba (who embraced him in the usual way) and attended his sacrifice. The priests had finished their report on the omens of the victim, when a freedman arrived with the message: 'The surveyors are here.' This was the agreed signal. Otho excused himself to the Emperor, saying that he had arranged to view a house that was for sale; then slipped out of the Palace by a back door and hurried to the rendezvous. (Another account makes him plead a chill, and leave his excuses with the Emperor's attendants, in case anyone should miss him.) At all events he went off in a closed sedan-chair of the sort used by women, and headed for the Camp, but jumped out and began to run when the bearers' pace flagged. As he paused to lace a shoe, his companions hoisted him on their shoulders and acclaimed him Emperor. The street crowds joined the procession as eagerly as if they were sworn accomplices, and Otho reached his headquarters to the sound of huzzas and the flash of drawn swords. He then dispatched a troop of cavalry to murder Galba and Piso and, avoiding all rhetorical appeals, told the troops merely that he would welcome whatever powers they might give him, but claim no others.

7. Towards evening Otho delivered a brief speech to the Senate claiming to have been picked up in the street and compelled to accept the Imperial power, but promising to respect the people's sovereign will. Hence he proceeded to the Palace, where he received fulsome congratulations and flattery from all present, making no protest even when the crowd called him Nero. Indeed, some historians record it as a fact that he replaced some of Nero's condemned busts and statues, and reinstated procurators and freedmen of his whom Galba had dismissed; and that the first decree of the new reign was a grant of half a million gold pieces for the completion of the Golden House.

Otho is said to have been haunted that night by Galba's ghost in a terrible nightmare; the servants who ran in when he screamed for help found him lying on the bedroom floor. After this he did everything in his power to placate the ghost; but next day, while he was taking the auspices, a hurricane sprang up and caused him a bad tumble — which made him mutter repeatedly: 'Playing the bagpipe is hardly my trade.'

8. Meanwhile, the armies in Germany took an oath of loyalty to Vitellius. Otho heard of this and persuaded the Senate to send a deputation, urging them to keep quiet, since an Emperor had already been appointed. But he also wrote Vitellius a personal letter: an invitation to become his father-in-law and share the empire with him. Vitellius, however, had already sent troops forward to march on Rome under their generals, and war was inevitable. Then, one night, the Guards gave such unequivocal proof of their faithfulness to Otho that it almost involved a massacre of the Senate. A detachment of sailors had been ordered to fetch some arms from the Praetorian Camp and take them aboard their vessels. They were carrying out their instructions at dusk when the Guards, suspecting treachery on the part of the Senate, rushed to the Palace in a leaderless mob and demanded that every Senator should die. Having driven away or murdered the senior officers who tried to stop them, they burst into the banqueting-hall, dripping with blood. 'Where is the Emperor?' they shouted; but as soon as they saw him busy with his meal they calmed down.

Otho set gaily out on his campaign, but haste prevented him from paying sufficient attention to the omens. The sacred shields used by the Leaping Priests had not yet been returned to the Temple of Mars — traditionally a bad sign — and this was 24 March, the day when the worshippers of the Goddess Cybele began their annual lamentation. Besides, the auspices were most unfavourable: at a sacrifice offered to Pluto the victim's intestines had a healthy look, which was exactly what they should not have had. Otho's departure was, moreover, delayed by a flooding of the Tiber; and at the twentieth milestone he found the road blocked by the ruins of a collapsed building.

9. Vitellius's forces being badly off for supplies and having little room for manoeuvre, Otho should have maintained the defensive, yet he rashly staked his fortunes on an immediate victory. Perhaps he suffered from nervousness and hoped to end the war before Vitellius himself arrived; perhaps he could not curb the offensive spirit of his troops. But when it came to the point he made Brescello his head-quarters and kept clear of the fighting. Although his army won three lesser engagements — in the Alps, at Piacenza, and at a place called 'Castor's' — they were tricked into a decisive defeat near Betriacum. There had been talk of an armistice, but Otho's troops, preparing to fraternize with the enemy while peace was discussed, found themselves suddenly committed to battle.

Otho decided on suicide. It is more probable that his conscience prevented him from continuing to hazard lives and treasure in a bid for sovereignty than that his men had become demoralized and unreliable; fresh troops stood in reserve for a counter-offensive and reinforcements came streaming down from Dalmatia, Pannonia, and Moesia. What is more, his defeated army were anxious to redeem their reputation, even without such assistance.

10. My own father, Suetonius Laetus, a tribune of the people, served with the Thirteenth Legion in this campaign. He often said afterwards that Otho had so deeply abhorred the thought of civil war while still a private citizen that he would shudder if the fates of Brutus and Cassius were mentioned at a banquet. And that he would not have moved against Galba to begin with, unless in the hope of a bloodless victory. Otho had now ceased to care what happened to himself, my father added, because of the deep impression made on him by the soldier who arrived at Brescello to report that the army had been defeated. When the garrison called him a bar and a cowardly deserter, the man fell on his sword at Otho's feet. Otho, greatly moved, issued a public statement that he would never again risk the lives of such gallant fellows. After embracing his brother, his nephew, and his friends, he dismissed them with orders to consult their own safety. Then he retired and wrote two letters: of consolation to his sister and of apology to Nero's widow, Messalina, whom he had meant to marry — at the same time begging her to bury him and preserve his memory. He next burned all his private correspondence to avoid incriminating anyone if it fell into Vitellius's hands, and distributed among the staff whatever loose cash he had with him.

11. While making final preparations for suicide Otho heard a disturbance outside, and was told that the men who had begun to drift away from camp were being arrested as deserters. He forbade his officers to award them any punishment, and saying: 'Let us add one extra night to life,' went to bed, but left his door open for several hours, in case anyone wished to speak with him. After drinking a glass of cold water and testing the points of two daggers, he put one of them under his pillow, closed the door and slept soundly. He awoke at dawn and promptly stabbed himself in the left side. His attendants heard him groan and rushed in; at first he could not decide whether to conceal or reveal the wound, which proved fatal. They buried him at once, as he had ordered them to do. His age was thirty-seven; and he had reigned for ninety-five days.

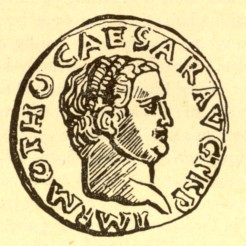

12.Otho, who did not look like a very courageous man, was of medium height, bow-legged, and with splay feet; but almost as fastidious about appearances as a woman. His entire body had been depilated, and a well-made toupee covered his practically bald head. He shaved every day, and since boyhood had always used a poultice of moist bread to retard the growth of his beard. He used to publicly celebrate the rites of Isis, wearing the approved linen smock.

The sensation caused by Otho's end was, I think, largely due to its contrast with the life he had led. Several soldiers visited the death-bed where they kissed his hands and feet, praising him as the bravest man they had ever known and the best Emperor imaginable; and afterwards they committed suicide themselves close to his funeral pyre. Stories are also current of men having killed one another in an excess of grief when the news of his death reached them. Thus many who had hated Otho while alive, loved him for the way he died; and he was even commonly believed to have killed Galba with the object not so much of becoming Emperor as of restoring the country's lost liberties.