(The introductory paragraphs on the origins of Caesar's family are lost in all manuscripts.)

1. GAIUS JULIUS CAESAR lost his father at the age of fifteen. During the next consulship, after being nominated to the priesthood of Jupiter, he broke an engagement, made for him while he was still a boy, to marry one Cossutia; for, though rich, she came of only equestrian family. Instead, he married Cornelia, daughter of that Cinna who had been Consul four times, and later she bore him a daughter named Julia. The Dictator Sulla tried to make Caesar divorce Cornelia; and when he refused stripped him of the priesthood, his wife's dowry, and his own inheritance, treating him as if he were a member of the popular party. Caesar disappeared from public view and, though suffering from a virulent attack of quartan fever, was forced to find a new hiding-place almost every night and bribe house holders to protect him from Sulla's secret police. Finally he won Sulla's pardon through the intercession of the Vestal Virgins and his near relatives Mamerius Aemilius and Aurelius Cotta. It is well known that, when the most devoted and eminent members of the aristocratic party pleaded Caesar's cause and would not let the matter drop, Sulla at last gave way. Whether he was divinely inspired or showed peculiar foresight is an arguable point, but these were his words:

'Very well then, you win! Take him! But never forget that the man whom you want me to spare will one day prove the ruin of the party which you and I have so long defended. There are many Marius's in this fellow Caesar.'

2. Caesar first saw military service in Asia, where he went as aide-de-camp to Marcus Thermus, the provincial governor-general. When Thermus sent Caesar to raise a fleet in Bithynia, he wasted so much time at King Nicomedes's court that a homosexual relationship between them was suspected, and suspicion gave place to scandal when, soon after his return to headquarters, he revisited Bithynia: ostensibly collecting a debt incurred there by one of his freedmen. However, Caesar's reputation improved later in the campaign, when Thermus awarded him the civic crown of oak-leaves, at the storming of Mytilene, for saving a fellow-soldier's life.

3. He also campaigned in Cilicia under Servilius Isauricus, but not for long, because the news of Sulla's death sent him hurrying back to Rome, where a revolt headed by Marcus Lepidus seemed to offer prospects of rapid advancement. Nevertheless, though Lepidus made him very advantageous offers, Caesar turned them down: he had small confidence in Lepidus's capacities, and found the political atmosphere less promising than he had been led to believe.

4. After this revolt was suppressed, Caesar brought a charge of extortion against Cornelius Dolabella, an ex-consul who had once been awarded a triumph, but failed to secure a sentence; so he decided to visit Rhodes until the resultant ill-feeling had time to die down, meanwhile taking a course in rhetoric from Apollonius Mole, the best living exponent of the art. Winter had already set in when he sailed for Rhodes and was captured by pirates off the island of Pharmacussa. They kept him prisoner for nearly forty days, to his intense annoyance; he had with him only a physician and two valets, having sent the rest of his staff away to borrow the ransom money. As soon as the stipulated fifty talents arrived (which make 12,000 gold pieces), and the pirates duly set him ashore, he raised a fleet and went after them. He had often smilingly sworn, while still in their power, that he would soon capture and crucify them; and this is exactly what he did. Then he continued to Rhodes, but Mithridates was now ravaging the near-by coast of Asia Minor; so, to avoid the charge of showing inertia while the allies of Rome were in danger, he raised a force of irregulars and drove Mithridates's deputy from the province — which confirmed the timorous and half-hearted cities of Asia in their allegiance.

5. On Caesar's return to Rome, the commons voted him the rank of colonel, and he vigorously helped their leaders to undo Sulla's legislation by restoring the tribunes of the people to their ancient powers. Then one Plotius introduced a bill for the recall from exile of Caesar's brother-in-law, Lucius Cinna — who, with other fellow-conspirators, had escaped to Spain after Lepidus's death and joined Sertorius. Caesar himself spoke in support of the bill, which was passed.

6. During his quaestorship he made the customary funeral speeches from the Rostra in honour of his aunt Julia and his wife Cornelia; and while eulogizing Julia's maternal and paternal ancestry, did the same for the Caesars too.

'Her mother,' he said, 'was a descendant of kings, namely the Royal Marcians, a family founded by the Roman King Ancus Marcius; and her father, of gods — since the Julians (of which we Caesars are a branch) reckon descent from the Goddess Venus. Thus Julia's stock can claim both the sanctity of kings, who reign supreme among mortals, and the reverence due to gods, who hold even kings in their power.'

He next married Pompeia, Quintus Pompey's daughter, who was also Sulla's grand-daughter, but divorced her on a suspicion of adultery with Publius Clodius; indeed, so persistent was the rumour of Clodius's having disguised himself as a woman and seduced her at the Feast of the Good Goddess, from which all men are excluded, that the Senate ordered a judicial inquiry into the alleged desecration of these sacred rites.

7. As quaestor Caesar was appointed to Western Spain, where the governor-general, who held praetorian rank, sent him off on an assize-circuit. At Cadiz he saw a statue of Alexander the Great in the Temple of Hercules, and was overheard to sigh impatiently: vexed, it seems, that at an age when Alexander had already conquered the whole world, he himself had done nothing in the least epoch-making. Moreover, when on the following night, much to his dismay, he had a dream of raping his own mother, the soothsayers greatly encouraged him by their interpretation of it: namely, that he was destined to conquer the earth, our Universal Mother.

8. At all events, he laid down his quaestorship at once, bent on performing some notable act at the first opportunity that offered. He visited the Latin colonists beyond the Po, who were bitterly demanding the same Roman citizenship as that granted to other townsfolk in Italy; and might have persuaded them to revolt, had not the Consuls realized the danger and garrisoned that district with the legions recently raised for the Cilician campaign.

9. Undiscouraged, Caesar soon made an even more daring attempt at revolution in Rome itself. A few days before taking up his aedileship, he was suspected of plotting with Marcus Crassus, an ex-consul; also with Publius Sulla and Lucius Autronius, who had jointly been elected to the consulship but found guilty of bribery and corruption. These four had agreed to wait until the New Year, and then attack the Senate House, killing as many senators as convenient. Crassus would then proclaim himself Dictator, and Caesar his Master of Horse; the government would be reorganized to suit their pleasure; Sulla and Autronius would be appointed Consuls.

Tanusius Geminus mentions their plot in his History; more information is given in Marcus Bibulus's Edicts and in the Orations of Gaius Curio the Elder. Another reference to it may be detected in Cicero's letter to Axius, where Caesar is said to have 'established in his consulship the monarchy which he had planned while only an aedile'. Tanusius adds that Crassus was prevented, either by scruples or by nervousness, from appearing at the appointed hour; and Caesar therefore did not give the agreed signal which, according to Curio, was letting his gown fall and expose the shoulder.

Both Curio and Marcus Actorius Naso state that Caesar also plotted with Gnaeus Piso, a young nobleman suspected of raising a City conspiracy and for that reason appointed Governor-general of Spain, although he had neither solicited nor qualified for the position. Caesar, apparently, was to lead a revolt in Rome as soon as Piso did so in Spain; the Ambranians and the Latins who lived beyond the Po would have risen simultaneously: But Piso's death cancelled the plan.

10. During his aedileslhip, Caesar filled the Comitium, the Forum, its adjacent basilicas, and the Capitol itself with a display of the material which he meant to use in his public shows; building temporary colonnades for the purpose. He exhibited wild-beast hunts and stage-plays; some at his own expense, some in co-operation with his colleague, Marcus Bibulus — but took all the credit in either case, so that Bibulus remarked openly:

'The Temple of the Heavenly Twins in the Forum is always simply called "Castor's"; and I always play Pollux to Caesar's Castor when we give a public entertainment together.'

Caesar also put on a gladiatorial show, but had collected so immense a troop of combatants that his terrified political opponents rushed a bill through the House, limiting the number of gladiators that anyone might keep in Rome; consequently far fewer pairs fought than had been advertised.

11. After thus securing the good will of the commons and their tribunes, Caesar tried to get himself elected Governor-General of Egypt by popular vote. His excuse for demanding so unusual an appointment was an outcry against the Alexandrians who had just deposed King Ptolemy, although the Senate had recognized him as an ally and friend of Rome. However, the aristocratic party opposed the measure; so, as aedile, Caesar took vengeance by replacing the public monuments — destroyed by Sulla many years ago — that had commemorated Marius's victories over Jugurtha, the Cimbrians, and the Teutons. Further, as judge of the Senatorial Court of Inquiry into Murder, he prosecuted men who had earned public bounties for bringing in the heads of Roman citizens outlawed by the aristocrats; although this rough justice had been expressly sanctioned in the Cornelian Laws.

12. He also bribed a man to bring a charge of high treason against Gaius Rabirius who, some years previously, had earned the Senate's gratitude by checking the seditious activities of Lucius Saturninus, a tribune. Caesar, chosen by lot to try Rabirius, pronounced the sentence with such satisfaction that, when Rabirius appealed to the people, the greatest argument in his favour was the judge's obvious prejudice.

13. Obliged to abandon his ambition of governing Egypt, Caesar stood for the office of Chief Pontiff, and used the most flagrant bribery to secure it. The story goes that, reckoning up the enormous debts thus contracted, he told his mother, as she kissed him goodbye on the morning of the poll, that if he did not return to her as Chief Pontiff he would not return at all. However, he defeated his two prominent rivals, both of whom were much older and more distinguished than himself, and the votes he won from their own tribes exceeded those cast for them in the entire poll.

14. When the Catilinarian conspiracy came to light, the whole House, with the sole exception of Caesar, then Praetor-elect, demanded the death penalty for Catiline and his associates. Caesar proposed merely that they should be imprisoned, each in a different town, and their estates confiscated. What was more, he so browbeat those senators who took a sterner line, by suggesting that the commons would conceive an enduring hatred for them if they persisted in this view, that Decimus Silanus, as Consul-elect, felt obliged to interpret his own proposal — which, however, he could not bring himself to recast — in a more liberal sense, begging Caesar not to misread it so savagely. And Caesar would have gained his point, since many senators (including the Consul Cicero's brother) had been won over to his view, had Marcus Cato not kept the irresolute Senate in line. Caesar continued to block proceedings until a body of Roman knights, serving as a defence force to the House, threatened to kill him unless he ceased his violent opposition. They even unsheathed their swords and made such passes at him that most of his companions fled, and the remainder huddled around, protecting him with their arms or their gowns. He was sufficiently impressed, not only to leave the House, but to keep away from it for the rest of that year.

15. On the first day of his praetorship, Caesar ordered Quintus Catulus to appear before the commons and explain why he had made so little progress with the restoration of the Capitol; demanding that Catulus's commission should be taken from him and entrusted, instead, to Gnaeus Pompey. However, the senators of the aristocratic party, who were escorting the newly-elected Consuls to their inaugural sacrifice in the Capitol, heard what was afoot, and came pouring downhill in a body to offer obstinate resistance. Caesar withdrew his proposal.

16. Caecilius Metellus, a tribune of the people, then defended his colleagues' veto by bringing in some highly inflammatory bills; and Caesar stubbornly championed them on the floor of the House until at last both Metellus and himself were suspended by a Senatorial decree. Nevertheless, he had the effrontery to continue holding his court, until warned that he would be removed by force. Thereupon he dismissed the lictors, took off his praetorian robe, and went quickly home, where he had decided to live in retirement because the times allowed him no other alternative.

On the following day, however, the commons made a spontaneous move towards Caesar's house, riotously offering to put him back on the tribunal; but he restrained their ardour. The Senate, who had hurriedly met to deal with this demonstration, were so surprised by his unexpectedly correct attitude that they sent a deputation of high officials to thank him publicly; then summoned him to the House where, with warm praises, they revoked their decree and confirmed him in his praetorship.

17. The next danger that threatened Caesar was the inclusion of his name in a list of Catilinarian conspirators handed to the Special Commissioner, Novius Niger, by an informer named Lucius Vettius; and also in another list laid before the Senate by Quintus Curius, who had been voted a public bounty as the first person to betray the plot. Curius claimed that this information came directly from Catiline, and Vettius went so far as to declare that he could produce a letter written to Catiline in Caesar's own hand.

Caesar would not lie down under this insult, and appealed to the Senatorial Records, which showed that, on Cicero's own admission, he had voluntarily come forward to warn him about the plot; and that Curius was not therefore entitled to the bounty. As for Vettius, who had been obliged to produce a bond when he made his revelations, this was declared forfeit and his goods seized; the commons, crowding around the Rostra, nearly tore him in pieces. Caesar thereupon sent Vettius off to gaol; and Novius Niger, the Commissioner, as well, for having let a magistrate of superior rank to himself be indicted at his tribunal.

18. The province of Western Spain was now allotted to Caesar. He relieved himself of the creditors who tried to keep him in Rome until he had paid his debts, by providing sureties for their eventual settlement. Then he took the illegal and unprecedented step of hurrying off before the Senate had either formally confirmed his appointment or voted him the necessary funds. He may have been afraid of being impeached while still a private citizen, or he may have been anxious to respond as quickly as possible to the appeals of our Spanish allies for help against aggression. At any rate, on his arrival in Spain he rapidly subdued the Lusitanian mountaineers, captured Brigantium, the capital of Galicia, and returned to Rome in the following summer with equal haste — not waiting until he had been relieved — to demand a triumph and stand for the consulship. But the day of the consular elections had already been announced. His candidacy could therefore not be admitted unless he entered the City as a civilian; and when a general outcry arose against his intrigues to be exempted from the regulations governing candidatures, he was faced with the alternative of forgoing the triumph or forgoing the consulship.

19. There were two other candidates: Lucius Lucceius and Marcus Bibulus. Caesar now approached Lucceius and suggested that they should join forces: but since Lucceius had more money and Caesar greater influence, it was agreed that Lucceius should finance their joint candidacy by bribing the voters. The aristocratic party got wind of this arrangement and, fearing that if Caesar were elected Consul, with a pliant colleague by his side, he would stop at nothing to gain his own ends, they authorized Marcus Bibulus to bribe the voters as heavily as Lucceius had done. Many aristocrats contributed to Bibulus's campaign funds, and Cato himself admitted that this was an occasion when even bribery might be excused as a legitimate means of preserving the Constitution.

Caesar and. Bibulus were elected Consuls, but the aristocrats continued to restrict Caesar's influence by ensuring that when he and Bibulus had completed their term, neither should govern a province garrisoned by large forces; they would be sent off somewhere 'to guard mountain-pastures and keep forests clear of brigands'. Infuriated by this slight, Caesar exerted his charm on Gnaeus Pompey, who had quarrelled with the Senate because they were so slow in approving the steps that he had taken to defeat King Mithridates of Pontus. He also succeeded in conciliating Pompey and Marcus Crassus — they were still at odds after their failure to agree on matters of policy while sharing the consulship. Pompey, Caesar, and Crassus now formed a triple pact, jointly swearing to oppose all legislation of which any one of them might disapprove.

20. Caesar's first act as Consul was to rule that a daily record of proceedings in the Senate, and in the People's Court, should be taken and published; he also revived the obsolete custom of having an orderly walk before him, during the months in which his colleague held the rods of office, while the lictors marched behind. Next, he introduced an agrarian law, and when Bibulus delayed its passage through the Senate by announcing that the omens were unfavourable, drove him from the Forum by force of arms. On the following day Bibulus lodged a complaint in the House, and when nobody dared move a vote of censure, or make any observation on this scandalous event — though decrees condemning minor breaches of the peace had often been passed — he felt so frustrated that he stayed at home for the rest of the term, satisfying his resentment with further announcements about unfavourable omens.

Caesar was thus enabled to govern alone and do very much as he pleased. It became a joke to sign and seal bogus documents: 'Executed during the Consulship of Julius and Caesar', rather than: ' . . . during the Consulship of Bibulus and Caesar'. And this lampoon went the rounds:

The event occured, as I recall, when Caesar governed Rome — Caesar, not Marcus Bibulus, who kept his seat at home.

The tribune Rullus had proposed to settle a number of poorer citizens on a Campanian plain called Stellas; and another agricultural district, also in Campania, had been declared public territory and farmed on behalf of the government. Caesar partitioned both these districts among fathers of three or more children, appointing a commission to choose the candidates, instead of letting them draw the customary lots. When the Roman tax-farmers asked for relief, he cancelled one-third of their obligations, but gave them frank warning not to bid too high for their contracts in future. He freely granted all other pleas, whatsoever, and either met with no opposition or intimidated anyone who dared intervene. Marcus Cato once tried to delay proceedings by talking out the debate, but Caesar had him forcibly ejected by a lictor and led off to prison. Lucius Lucullus went a little too far in opposing Caesar's policy, whereupon Caesar so terrified him by threats of prosecution for the part he had supposedly played in the Mithridatic War that Lucullus fell on his knees and begged Caesar's pardon. Hearing that Cicero had been making a doleful speech in court about the evils of his times, Caesar at once granted the long-standing plea of Cicero's enemy, Publius Clodius, to be transferred from patrician to plebeian rank; rushing this measure through the House at three o'clock, just before the adjournment. Finally, he began an attack on his aristocratic opponents as a body by bribing an informer, who appeared on the Rostra and announced that some of them had tried to make him assassinate Pompey. As had been arranged, the informer mentioned a few names, but the whole affair was so suspicious that nobody paid much attention and Caesar, realizing that he had been too hasty, is said to have poisoned his agent.

21. Caesar then married Calpurnia, daughter of Lucius Piso, his successor in the consulship; and at the same time betrothed Julia to Gnaeus Pompey, thus breaking her previous engagement to Servilius Caepio, who had recently given him a great deal of support in the struggle against Bibulus. He now always called on Pompey to open debates in the House, though having hitherto reserved this honour for Crassus; thereby flouting the tradition that a Consul should continue, throughout the year, to preserve the order of precedence established for speakers on New Year's Day.

22. Having thus secured the goodwill of his father-in-law Piso and his son-in-law Pompey, Caesar surveyed the many provinces open to him and chose Gaul as being the likeliest to supply him with wealth and triumphs. True, he was at first appointed Governor-General only of Cisalpine Gaul and Illyria — the proposal came from Vatinius — but afterwards the Senate added Transalpine Gaul to his jurisdiction, fearing that if this were denied him, the commons would insist that he should have it.

His elation was such that he could not refrain from boasting to a packed House, some days later, that having now gained his dearest wish, to the annoyance and grief of his opponents, he would proceed to 'stamp upon their persons'. When someone interjected with a sneer that a woman would not find this an easy feat, he answered amicably:

'Why note Semiramis was supreme in Syria, and the Amazons once ruled over a large part of Asia.'

23. At the close of his consulship the praetors Gaius Memmius and Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus demanded an inquiry into his official conduct during the past year. Caesar referred the matter to the Senate, who would not discuss it, so after three days had been wasted in idle recriminations, he left for Gaul. His quaestor was at once charged with various irregularities, as a first step towards his own impeachment. Then Lucius Antistius, a tribune of the people, arraigned Caesar who, however, appealed to the whole college of tribunes, pleading absence on business of national importance; and thus staved off the trial.

To prevent a recurrence of this sort of trouble he made a point of putting the chief magistrates of each new year under some obligation to him, and refusing to support any candidates, or allow them to be elected, unless they promised to defend his cause while he was absent from Rome. He had no hesitation in holding some of them to their promises by an oath, or even a written contract.

24. At last Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus stood for the consulship and openly threatened that, once elected, lie would remove Caesar from his military command, having failed to do this while praetor. So Caesar called upon Pompey and Crassus to visit Lucca, which lay in his province, and there persuaded them to prolong his governorship of Gaul for another five years, and to oppose Domitius's candidature.

This success encouraged Caesar to expand his regular army with legions raised at his own expense: one even recruited in Transalpine Gaul and called Alauda (Gallic for 'The Crested Lark'), which he trained and equipped in Roman style. Later he made every Alauda legionary a full citizen.

He now lost no opportunity of picking quarrels — however flimsy the pretext — with allies as well as hostile and barbarous tribes, and marching against them; the danger of this policy never occurred to him. At first the Senate set up a commission of inquiry into the state of the Gallic provinces, and some speakers went so far as to recommend that Caesar should be handed over to the enemy. But the more successful his campaigns, the more frequent the public thanksgivings voted; and the holidays that went with them were longer than any general before him had ever earned.

25. Briefly, his nine years' governorship produced the following results. He reduced to the form of a province the whole of Gaul enclosed by the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Cevennes, the Rhine, and the Rhone — about 640,000 square miles — except for certain allied states which had given him useful support; and exacted an annual tribute of 400,000 gold pieces.

Caesar was the first Roman to build a military bridge across the Rhine and cause the Germans on the farther bank heavy losses. He also invaded Britain, a hitherto unknown country, and defeated the natives, from whom he exacted a large sum of money as well a hostages for future good behaviour. He met with only three serious reverses: in Britain, when his fleet was all but destroyed by a gale; in Gaul, when one of his legions was routed at Gergovia among the Auvergne mountains; and on the German frontier, when his generals Titurius and Aurunculeius were ambushed and killed.

26. During these nine years Caesar lost, one after the other, his mother, his daughter, and his grandson. Meanwhile, the assassination of Publius Clodius had caused such an outcry that the Senate voted for the appointment, in future, of only a single Consul; naming Pompey as their choice. When the tribunes of the people wanted Caesar to stand as Pompey's colleague, Caesar asked whether they would not persuade the commons to let him do so without visiting Rome; his governorship of Gaul, he wrote, was nearly at an end, and he preferred not to leave until his conquests had been completed.

Their granting of this concession so fired Caesar's ambitions that he neglected no expense in winning popularity, both as a private citizen and as a candidate for his second consulship. He began building a new Forum with the spoils taken in Gaul, and paid more than a million gold pieces for the site alone. Then he announced a gladiatorial show and a public banquet in memory of his daughter Julia — an unprecedented event; and, to create as much excitement among the commons as possible, had the banquet catered for partly by his own household, partly by the market contractors. He also issued an order that any well known gladiator who failed to win the approval of the Circus should be forcibly rescued from execution and reserved for the coming show. New gladiators were also trained, not by the usual professionals in the schools, but in private houses by Roman knights and even senators who happened to be masters-at-arms. Letters of his survive, begging these trainers to give their pupils individual instruction in the art of fighting. He fixed the daily pay of the regular soldiers at double what it had been. Whenever the granaries were full he would make a lavish distribution to the army, without measuring the amount, and occasionally gave every man a Gallic slave.

27. To preserve Pompey's friendship and renew the family ties dissolved by Julia's death he offered him the hand of his sister's granddaughter Octavia, though she had already married Gaius Marcellus, and in return asked leave to marry Pompey's daughter, who was betrothed to Faustus Sulla. Having now won all Pompey's friends, and most of the Senate, to his side with loans at a low rate of interest, or interest-free, he endeared himself to persons of less distinction too by handing out valuable presents, whether or not they asked for them. His beneficiaries included the favourite slaves or freedmen of prominent men.

Caesar thus became the one reliable source of help to all who were in legal difficulties, or in debt, or living beyond their means; and refused help only to those whose criminal record was so black, or whose purse so empty, or whose tastes were so expensive, that even he could do nothing for them. He frankly told such people: 'What you need is a civil war.'

28. Caesar took equal pains to win the esteem of kings and provincial authorities by offering them gifts of prisoners, a thousand at a time, or lending them troops whenever they asked, and without first obtaining official permission from the Senate or people. He also presented the principal cities of Asia and Greece with magnificent public works, and did the same for those of Italy, Gaul, and Spain. Everyone was amazed by this liberality and wondered what the sequel would be.

At last Marcus Claudius Marcellus, the Consul, announced in the House that he intended to raise a matter of vital public interest; and then proposed that, since the Gallic War had now ended in victory, Caesar should be relieved of his command before his term as Governor-General expired; that a successor should be appointed; and that the armies in Gaul should be disbanded. He further proposed that Caesar should be forbidden to stand for the consulship without appearing at Rome in person, since a decree against irregularities of this sort still appeared on the Statute Book.

Here Marcellus was on firm legal ground. Pompey, when he introduced a bill regulating the privileges of state officials, had omitted to make a special exception for Caesar in the clause debarring absentees from candidacy; or to correct this oversight before the bill had been passed, engraved on a bronze tablet, and registered at the Public Treasury. Nor was Marcellus content to oust Caesar from his command and cancel the privilege already voted him: namely to stand for the consulship in absentia. He also asked that the colonists whom Caesar had settled at Como under the Vatinian Act should lose their citizenship. This award, he said, had been intended to further Caesar's political ambitions and lacked legal sanction.

29. The news infuriated Caesar, but he had often been reported as saying: 'Now that I am the leading Roman of my day, it will be harder to put me down a peg than degrade me to the ranks.' So he resisted stubbornly; persuading the tribunes of the people to veto Marcellus's bills and at the same time enlisting the help of Servius Sulpicius, Marcellus's colleague. When, in the following year, Marcellus was succeeded in office by his cousin Gaius, who adopted a similar policy, Caesar again won over the other Consul — Aemilius Paulus — with a heavy bribe; and also bought Gaius Curio, the most energetic tribune of the people.

Realizing, however, that the aristocratic party had made a determined stand, and that both the new Consuls-elect were unfriendly to him, he appealed to the Senate, begging them in a written address not to cancel a privilege voted him by the commons, without forcing all other governors-general to resign their commands at the same time as he did. But this was read as meaning that he counted on mobilizing his veteran troops sooner than Pompey could his raw levies. Next, Caesar offered to resign command of eight legions and quit Transalpine Gaul if he might keep two legions and Cisalpine Gaul, or at least Illyricum and one legion, until he became Consul.

30. Since the Senate refused to intervene on his behalf in a matter of such national importance, Caesar crossed into Cisalpine Gaul, where he held his regular assizes, and halted at Ravenna. He was resolved to invade Italy if force were used against the tribunes of the people who had vetoed the Senate's decree disbanding his army by a given date. Force was, in effect, used and the tribunes fled towards Cisalpine Gaul; which became Caesar's pretext for launching the Civil War. Additional motives are suspected, however: Pompey's comment was that, because Caesar had insufficient capital to carry out his grandiose schemes or give the people all that they had been encouraged to expect on his return, he chose to create an atmosphere of political confusion.

Another view is that he dreaded having to account for the irregularities of his first consulship, during which he had disregarded auspices and vetoes, and defied the Constitution; for Marcus Cato had often sworn to impeach him as soon as the legions were disbanded. Moreover, people said at the time, frankly enough, that should Caesar return from Gaul as a private citizen he would be tried in a court ringed around with armed men, as Titus Annius Milo had lately been at Pompey's orders. This sounds plausible enough, because Asinius Pollio records in his History that when Caesar, at the Battle of Pharsalus, saw his enemies forced to choose between massacre and flight, he said, in these very words:

'They brought it on themselves. They would have condemned me to death regardless of all my victories — me, Gaius Caesar — had I not appealed to my army for help.'

It has also been suggested that constant exercise of power gave Caesar a love of it; and that, after weighing his enemies' strength against his own, he took this chance of fulfilling his youthful dreams by making a bid for the monarchy. Cicero seems to have come to a similar conclusion: in the third book of his Essay on Duty, he records that Caesar quoted the following lines from Euripides's Phoenician Women on several occasions:

Is crime consonant with nobility?

Then noblest is the crime of tyranny —

In all things else obey the laws of Heaven.

31. Accordingly, when news reached him that the tribunes' veto had been disallowed, and that they had fled the City, he at once sent a few battalions ahead with all secrecy, and disarmed suspicion by himself attending a theatrical performance, inspecting the plans of a school for gladiators which he proposed to build, and dining as usual among a crowd of guests. But at dusk he borrowed a pair of mules from a bakery near Headquarters, harnessed them to a gig, and set off quietly with a few of his staff. His lights went out, he lost his way, and the party wandered about aimlessly for some hours; but at dawn found a guide who led them on foot along narrow lanes, until they came to the right road. Caesar overtook his advanced guard at the river Rubicon, which formed the frontier between Gaul and Italy. Well aware how critical a decision confronted him, he turned to his staff, remarking:

'We may still draw back but, once across that little bridge, we shall have to fight it out'

32. As he stood, in two minds, an apparition of superhuman size and beauty was seen sitting on the river bank playing a reed pipe. A party of shepherds gathered around to listen and, when some of Caesar's men broke ranks to do the same, the apparition snatched a trumpet from one of them, ran down to the river, blew a thunderous blast, and crossed over. Caesar exclaimed:

'Let us accept this as a sign from the Gods, and follow where they beckon, in vengeance on our double-dealing enemies. The die is cast.'

33. He led his army to the farther bank, where he welcomed the tribunes of the people who had fled to him from Rome. Then he tearfully addressed the troops and, ripping open his tunic to expose his breast, begged them to stand faithfully by him. The belief that he then promised to promote every man present to the Equestrian Order is based on a misunderstanding. He had accompanied his pleas with the gesture of pointing to his left hand, as he declared that he would gladly reward those who championed his honour with the very seal ring from his thumb; but some soldiers on the fringe of the assembly who saw him better than they could hear his words, read too much into the gesture. They put it about that Caesar had promised them all the right to wear a knight's gold ring, and the 4,000 gold pieces required to support a knighthood.

34. Here follows a brief account of Caesar's subsequent movements. He occupied Umbria, Picenum, and Tuscany; captured Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus who had been illegally named as his successor in Gaul and was holding Corfinium for the Senate; let him go free; and then marched along the Adriatic coast to Brindisi, where Pompey and the Consuls had fled from Rome on their way to Epirus. When his efforts to prevent their crossing the straits proved ineffective, he marched on Rome, entered it, summoned the Senate to review the political situation, and then hurriedly set off for Spain; Pompey's strongest forces were stationed there under the command of his friends Marcus Petreius, Lucius Afranius, and Marcus Varro. Before leaving, Caesar told his household: 'I am off to meet an army without a leader; when I return I shall meet a leader without an army.' Though delayed by the siege of Marseilles, which had shut its gates against him, and by a failure of his commissariat, he won a rapid arid overwhelming victory.

35. Caesar returned by way of Rome, crossed the Adriatic and, after blockading Pompey near the Illyrian town of Dyrrhachium for nearly four months, behind an immense containing works, routed him at Pharsalus in Thessaly. Pompey fled to Alexandria; Caesar followed, and when he found that King Ptolemy had murdered Pompey and was planning to murder him as well, declared war. This proved to be a most difficult campaign, fought during winter within the city walls of a well-equipped and cunning enemy; but though caught off his guard, and without military supplies of any kind, Caesar was victorious. He then handed over the government of Egypt to Queen Cleopatra and her younger brother; fearing that, if made a Roman province, it might one day be held against his fellow-countrymen by some independent-minded governor-general. From Alexandria he proceeded to Syria, and from Syria to Pontus, news having come that Pharnaces, son of the famous Mithridates, had taken advantage of the confused situation and already gained several successes. Five days after his arrival, and four hours after catching sight of Pharnaces, Caesar won a crushing victory at Zela; and commented drily on Pompey's good fortune in having built up his reputation for generalship by victories over such poor stuff as this. Then he beat Scipio and King Juba at Thapsus in North Africa, where the remnants of the Pompeian party were being reorganized; and Pompey's two sons at Munda in Spain.

36. Throughout the Civil War Caesar was never defeated himself; but, of his generals, Gaius Curio was killed fighting against King Juba; Gaius Antonius was captured off Illyricum; Publius Dolabella lost another fleet off Illyricum; and Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus had his army destroyed in Pontus. Yet, though invariably successful, he twice came close to disaster: at Dyrrhachium, where Pompey broke his blockade and forced him to retreat — Caesar remarked when Pompey failed to pursue him: 'He does not know how to win wars' — and in the final battle at Munda, where all seemed lost and he even considered suicide.

37. After defeating Scipio, Caesar celebrated four triumphs in one month with a few days' interval between them; and, after defeating young Pompey, a fifth. These triumphs were the Gallic— the first and most magnificent — the Alexandrian, the Pontic, the African, and lastly the Spanish. Each differed completely from the others in its presentation.

As Caesar rode through the Velabrum on the day of his Gallic triumph, the axle of his triumphal chariot broke, and he nearly took a toss; but afterwards ascended to the Capitol between two lines of elephants, forty in all, which acted as his torch-bearers. In the Pontic triumph one of the decorated wagons, instead of a stage-set representing scenes from the war, like the rest, carried a simple three-word inscription:

CAME, SAW, CONQUERED!

This referred to the speed with which the war had been won.

38. Every infantryman of Caesar's veteran legions earned a war gratuity of 240 gold pieces, in addition to the twenty paid at the outbreak of hostilities, and a farm. These farms could not be grouped together without evicting former owners, but were scattered all over the countryside. Every member of the commons received ten pecks of grain and ten pounds of oil as a bounty, besides the three gold pieces which Caesar had promised at first and now raised to five, by way of interest on the four years' delay in payment. He added a popular banquet and a distribution of meat; also a dinner to celebrate his victory at Munda, but decided that this had not been splendid enough and, five days later, served a second more succulent one.

39. His public shows were of great variety. They included a gladiatorial contest, stage-plays for every quarter of Rome performed in several languages, chariot-races in the Circus, athletic competitions, and a mock naval battle. At the gladiatorial contest in the Forum, a man named Furius Leptinus, of patrician family, fought Quinitus Calpenus, a barrister and former senator, to the death. The sons of petty kings from Asia and Bithynia danced the Pyrrhic sword dance. One of the plays was written and acted by Decimus Laberius, a Roman knight, who forfeited his rank by so doing; but after the performance he was given five thousand gold pieces and had his gold ring, the badge of equestrian rank, restored to him — so that he could walk straight from stage to orchestra, where fourteen rows of seats were reserved for his Order. A broad ditch had been dug around the race-course, now extended at either end of the Circus, and the contestants were young noblemen who drove four-horse and two-horse chariots or rode pairs of horses, jumping from back to back. The socalled Troy Game, a sham fight supposedly introduced by Aeneas, was performed by two troops of boys, one younger than the other.

Wild-beast hunts took place five days running, and the entertainment ended with a battle between two armies, each consisting of 500 infantry, twenty elephants, and thirty cavalry. To let the camps be pitched facing each other, Caesar removed the central barrier of the Circus, around which the chariots ran. Athletic contests were held in a temporary stadium on the Campus Martius, and lasted for three days.

The naval battle was fought on an artificial lake dug in the Lesser Codeta, between Tyrian and Egyptian ships, with two, three, or four banks of oars, and heavily manned. Such huge numbers of visitors flocked to these shows from all directions that many of them had to sleep in tents pitched along the streets or roads, or on roof tops; and often the pressure of the crowd crushed people to death. The victims included two senators.

40. Caesar next turned his attention to domestic reforms. First he reorganized the Calendar which the Pontiffs had allowed to fall into such disorder, by intercalating days or months as it suited them, that the harvest and vintage festivals no longer corresponded with the appropriate seasons. He linked the year to the course of the sun by lengthening it from 355 days to 365, abolishing the short extra month intercalated after every second February, and adding an entire day every fourth year. But to make the next first of January fall at the right season, he drew out this particular year by two extra months, inserted between November and December, so that it consisted of fifteen, including the intercalary one inserted after February in the old style.

41. He brought the Senate up to strength by creating new patricians, and increased the yearly quota of praetors, aediles, and quaestors, as well as of minor officials; reinstating those degraded by the Censors or condemned for corruption by a jury. Also, he arranged with the commons that, apart from the Consul, half the magistrates should be popularly elected and half nominated by himself. Allowing even the sons of proscribed men to stand, he circulated brief directions to the voters. For instance: 'Caesar the Dictator to such-and-such a tribe of voters: I recommend So-and-so to you for office.' He limited jury service to knights and senators, disqualifying the Treasury tribunes — these were commoners who collected the tribute and paid the army.

Caesar changed the old method of registering voters: he made the City landlords help him to complete the list, street by street, and reduced from 320,000 to 150,000 the number of householders who might draw free grain. To do away with the nuisance of having to summon everyone for enrolment periodically, he made the praetors keep their register up to date by replacing the names of dead men with those of others not yet listed.

42. Since the population of Rome had been considerably diminished by the transfer of 80,000 men to overseas colonies, he forbade any citizen between the ages of twenty and forty to absent himself from Italy for more than three years in succession. Nor might any senator's son travel abroad unless as a member of some magistrate's household or staff; and at least a third of the cattlemen employed by graziers had to be free-born. Caesar also granted the citizenship to all medical practitioners and professors of liberal arts resident in Rome, thus inducing them to remain and tempting others to follow suit.

He disappointed popular agitators by cancelling no debts, but in the end decreed that every debtor should have his property assessed according to pre-war valuation and, after deducting the interest already paid directly, or by way of a banker's guarantee, should satisfy his creditors with whatever sum that might represent. Since prices had risen steeply, this left debtors with perhaps a fourth part of their property. Caesar dissolved all workers' guilds except the ancient ones, and increased the penalties for crime; and since wealthy men had less compunction about committing major offences, because the worst that could happen to them was a sentence of exile, he punished murderers of fellow-citizens (as Cicero records) by the seizure of either their entire property, or half of it.

43. In his administration of justice he was both conscientious and severe, and went so far as to degrade senators found guilty of extortion. Once, when an ex-praetor married a woman on the day after her divorce from another man, he annulled the union, although adultery between them was not suspected.

He imposed a tariff on foreign manufactures; forbade the use, except on stated occasions, of litters, and the wearing of either scarlet robes or pearls by those below a certain rank and age. To implement his laws against luxury he placed inspectors in different parts of the market to seize delicacies offered for sale in violation of his orders; sometimes he even sent lictors and guards into dining-rooms to remove illegal dishes, already served, which his watchmen had failed to intercept.

44. Caesar continually undertook great new works for the embellishment of the City, or for the Empire's protection and enlargement. His first projects were a temple of Mars, the biggest in the world, to build which he would have had to fill up and pave the lake where the naval sham-fight had been staged; and an enormous theatre sloping down from the Tarpeian Rock on the Capitoline Hill.

Another task he set himself was the reduction of the Civil Code to manageable proportions, by selecting from the unwieldy mass of statutes only the most essential, and publishing them in a few volumes. Still another was to provide public libraries, by commissioning Marcus Varro to collect and classify Greek and Latin books on a comprehensive scale. His engineering schemes included the draining of the Pomptine Marshes and of Lake Fucinus; also a highway running from the Adriatic across the Apennines to the Tiber; and a canal to be cut through the isthmus of Corinth. In the military field he planned an expulsion of the Dacians from Pontus and Thrace, which they had recently occupied, and then an attack on Parthia by way of Lesser Armenia; but decided not to risk a pitched battle until he had familiarized himself with Parthian tactics.

All these schemes were cancelled by his assassination. Before describing that, I should perhaps give a brief description of his appearance, personal habits, dress, character, and conduct in peace and war.

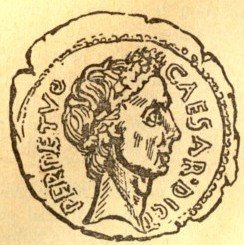

45. Caesar is said to have been tall, fair, and well-built, with a rather broad face and keen, dark-brown eyes. His health was sound, apart from sudden comas and a tendency to nightmares which troubled him towards the end of his life; but he twice had epileptic fits while on campaign. He was something of a dandy, always keeping his head carefully trimmed and shaved; and has been accused of having certain other hairy parts of his body depilated with tweezers. His baldness was a disfigurement which his enemies harped upon, much to his exasperation; but he used to comb the thin strands of hair forward from his poll, and of all the honours voted him by the Senate and People, none pleased him so much as the privilege of wearing a laurel wreath on all occasions — he constantly took advantage of it.

His dress was, it seems, unusual: he had added wrist-length sleeves with fringes to his purple-striped senatorial tunic, and the belt which he wore over it was never tightly fastened — hence Sulla's warning to the aristocratic party: 'Beware of that boy with the loose clothes!'

46. Caesar's first home was a modest house in the Subura quarter, but later, as Chief Pontiff, he used the official residence on the Sacred Way. Contemporary literature contains frequent references to his fondness for luxurious living. Having built a country mansion at Nervi from the foundations up, one story goes, he found so many features in it to dislike that, although poor at the time and heavily in debt, he tore the whole place down. It is also recorded that he carried tessellated and mosaic pavements with him on his campaigns.

47. Fresh-water pearls seem to have been the lure that prompted his invasion of Britain; he would sometimes weigh them in the palm of his hand to judge their value, and was also a keen collector of gems, carvings, statues, and Old Masters. So high were the prices he paid for slaves of good character and attainments that he became ashamed of his extravagance and would not allow the sums to be entered in his accounts.

48. I find also that, while stationed abroad, he always had dinner served in two separate rooms: one for his officers and Greek friends, the other for Roman citizens and the more important provincials. He paid such strict attention to his domestic economy, however small the detail, that he once put his baker in irons for giving him a different sort of bread from that served to his guests; and executed a favourite freedman for committing adultery with a knight's wife, although no complaint had been lodged by the husband.

49. The only specific charge of unnatural practices ever brought against him was that he had been King Nicomedes's catamite — always a dark stain on his reputation and frequently quoted by his enemies. Licinius Calvus published the notorious verses:

The riches of Bithynia's King

Who Caesar on his couch abused.

Dolabella called him 'the Queen's rival and inner partner of the royal bed', and Curio the Elder: 'Nicomedes's Bithynian brothel'. Bibulus, Caesar's colleague in the consulship, described him in an edict as 'the Queen of Bithynia . . . who once wanted to sleep with a monarch, but now wants to be one'. And Marcus Brutus recorded that, about the same time, one Octavius, a scatterbrained creature who would say the first thing that came into his head, walked into a packed assembly where he saluted Pompey as 'King' and Caesar as 'Queen'. These can be discounted as mere insults, but Gaius Memmius directly charges Caesar with having joined a group of Nicomedes's debauched young friends at a banquet, where he acted as the royal cup-bearer; and adds that certain Roman merchants, whose names he supplies, were present as guests. Cicero, too, not only wrote in several letters:

Caesar was led by Nicomedes's attendants to the royal bedchamber, where he lay on a golden couch, dressed in a purple shift . . . So this descendant of Venus lost his virginity in Bithynia,

but also once interrupted Caesar while he was addressing the House in defence of Nicomedes's daughter Nysa and listing his obligations to Nicomedes himself. 'Enough of that,' Cicero shouted, 'if you please! We all know what he gave you, and what you gave him in return.' Lastly, when Caesar's own soldiers followed his decorated chariot in the Gallic triumph, chanting ribald songs, as they were privileged to do, this was one of them:

Gaul was brought to shame by Caesar;

By King Nicomedes, he.

Here comes Caesar, wreathed in triumph

For his Gallic victory!

Nicomedes wears no laurels,

Though the greatest of the three.

50.. His affairs with women are commonly described as numerous and extravagant: among those of noble birth whom he is said to have seduced were Servius Sulpicius's wife Postumia; Aulus Gabinius's wife Lollia; Marcus Crassus's wife Tertulla; and even Gnaeus Pompey's wife Mucia. Be this how it may, both Curio the Elder and Curio the Younger reproached Pompey for having married Caesar's daughter Julia, when it was because of Caesar, whom he had often despairingly called 'Aegisthus', that he divorced Mucia, mother of his three children. This Aegisthus had been the lover of Agamemnon's wife Clytaemnestra.

But Marcus Brutus's mother Servilia was the woman whom Caesar loved best, and in his first consulship he brought her a pearl worth 60,000 gold pieces. He gave her many presents during the Civil War, as well as knocking down certain valuable estates to her at a public auction for a song. When surprise was expressed at the low price, Cicero made a neat remark: 'It was even cheaper than you think, because a third (tertia) had been discounted.' Servilia, you see, was also suspected at the time of having prostituted her daughter Tertia to Caesar.

51. That he had love-affairs in the provinces, too, is suggested by another of the ribald verses sung during the Gallic triumph:

Home we bring our bald whoremonger;

Romans, lock your wives away!

All the bags of gold you lent him

Went his Gallic tarts to pay.

52. Among his mistresses were several queens — including Eunoë, wife of Bogudes the Moor whom, according to Marcus Actorius Naso, he loaded with presents; Bogudes is said to have profited equally. The most famous of these queens was Cleopatra of Egypt. He often feasted with her until dawn; and they would have sailed together in her state barge nearly to Ethiopia had his soldiers consented to follow him. He eventually summoned Cleopatra to Rome, and would not let her return to Alexandria without high titles and rich presents. He even allowed her to call the son whom she had borne him 'Caesarion'. Some Greek historians say that the boy closely resembled Caesar in features as well as in gait. Mark Antony informed the Senate that Caesar had, in fact, acknowledged Caesarion's paternity, and that other friends of Caesar's, including Gaius Matins and Gaius Oppius, were aware of this. Oppius, however, seems to have felt the need of clearing his friend's reputation; because he published a book to prove that the boy whom Cleopatra had fathered on Caesar was not his at all.

A tribune of the people named Helvius Cinna informed a number of people that, following instructions, he had drawn up a bill for the commons to pass during Caesar's absence from Rome, legitimizing his marriage with any woman, or women, he pleased — 'for the procreation of children'. And to emphasize the bad name Caesar had won alike for unnatural and natural vice, I may here record that the Elder Curio referred to him in a speech as: 'Every woman's husband and every man's wife'.

53. Yet not even his enemies denied that he drank abstemiously. An epigram of Marcus Cato's survives: 'Caesar was the only sober man who ever tried to wreck the Constitution'; and Gaius Oppius relates that he cared so little for good food that when once he attended a dinner party where rancid oil had been served by mistake, and all the other guests refused it, Caesar helped himself more liberally than usual, to show that he did not consider his host either careless or boorish.

54. He was not particularly honest in money matters, either while a provincial governor or while holding office at Rome. Several memoirs record that as Governor-General of Western Spain he not only begged his allies for money to settle his debts, but wantonly sacked several Lusitanian towns, though they had accepted his terms and opened their gates to welcome him.

In Gaul he plundered large and small temples of their votive offerings, and more often gave towns over to pillage because their inhabitants were rich than because they had offended him. As a result he collected larger quantities of gold than he could handle, and began selling it for silver, in Italy and the provinces, at 750 denarii to the pound — which was about two-thirds of the official exchange rate.

In the course of his first consulship he stole 3,000 lb of gold from the Capitol, and replaced it with the same weight of gilded bronze. He sold alliances and thrones for cash, making King Ptolemy XII of Egypt give him and Pompey nearly 1,500,000 gold pieces; and later paid his Civil War army, and the expenses of his triumphs and entertainments, by open extortion and sacrilege.

55.. Caesar equalled, if he did not surpass, the greatest orators and generals the world had ever known. His prosecution of Dolabella unquestionably placed him in the first rank of advocates; and Cicero, discussing the matter in his Brutus, confessed that he knew no more eloquent speaker than Caesar 'whose style is chaste, pellucid, and grand, not to say noble'. Cicero also wrote to Cornelius Nepos:

'Very well, then! Do you know any man who, even if he has concentrated on the art of oratory to the exclusion of all else, can speak better than Caesar? Or anyone who makes so many witty remarks? Or whose vocabulary is so varied and yet so exact?'

Caesar seems to have modelled his style, at any rate when a beginner, on Caesar Strabo — part of whose Defence of the Sardinians he borrowed verbatim for use in a trial oration of his own; he was then competing with other advocates for the right to plead a cause. It is said that he pitched his voice high in speaking, and used impassioned gestures which far from displeased his audience.

Several of Caesar's undoubted speeches survive; and he is credited with others that may or may not have been his. Augustus said that the 'Defence of Quintus Metellus' could hardly have been published by Caesar himself, and that it appeared to be a version taken down by shorthand writers who could not keep up with his rapid delivery. He was probably right, because on examining several manuscripts of the speech I find that even the title is given as 'A Speech Composed for Metellus' — although Caesar intended to deliver it in defence of Metellus and himself against a joint accusation.

Augustus also doubted the authenticity of Caesar's 'Address to my Soldiers in Spain'. It is written in two parts, one speech supposedly delivered before the first battle, the other before the second — though on the latter occasion, at least, according to Asinius Pollio, the enemy's attack gave Caesar no time to address his troops at all.

56. He left memoirs of his war in Gaul, and of his civil war against Pompey; but no one knows who wrote those of the Alexandrian, African, and Spanish campaigns. Some say that it was his friend Oppius; others that it was Hirtius, who also finished 'The Gallic War', left incomplete by Caesar, adding a final book. Cicero, also in the Brutus, observes:

'Caesar wrote admirably; his memoirs are cleanly, directly and gracefully composed, and divested of all rhetorical trappings. And while his sole intention was to supply historians with factual material, the result has been that several fools have been pleased to primp up his narrative for their own glorification; but every writer of sense has given the subject a wide berth.'

Hirtius says downrightly:

'These memoirs are so highly rated by all judicious critics that the opportunity of enlarging and improving on them, which he purports to offer historians, seems in fact withheld from them. And, as his friends, we admire this feat even more than strangers can: they appreciate the faultless grace of his style, we know how rapidly and easily he wrote.'

Asinius Polo, however, believes that the memoirs show signs of carelessness and inaccuracy: Caesar, he holds, did not always check the truth of the reports that came in, and was either disingenuous or forgetful in describing his own actions. Pollio adds that Caesar must have planned a revision.

Among his literary remains are two books of An Essay on Analogy, two more of Answers to Cato, and a poem, The Journey. He wrote An Essay on Analogy while coming back over the Alps after holding assizes in Cisalpine Gaul; Answers to Cato in the year that he won the battle of Munda; and The Journey during the twenty-four days he spent on the road between Rome and Western Spain.

Many of the letters and despatches sent by him to the Senate also survive, and he seems to have been the first statesman who reduced such documents to book form; previously, Consuls and governor-generals had written right across the page, not in neat columns. Then there are his letters to Cicero ; and his private letters to friends, the more confidential passages of which he wrote in cypher: to understand their apparently incomprehensible meaning one must number the letters of the alphabet from 1 to 22, and then replace each of the letters that Caesar has used with the one which occurs four numbers lower — for instance, D stands for A.

It is said that in his boyhood and early youth he also wrote pieces called In Praise of Hercules and The Tragedy of Oedipus and Collected Sayings; but nearly a century later the Emperor Augustus sent Pompeius Macer, his Surveyor of Libraries, a brief, frank letter forbidding him to circulate these minor works.

57. Caesar was a most skilful swordsman and horseman, and showed surprising powers of endurance. He always led his army, more often on foot than in the saddle, went bareheaded in sun and rain alike, and could travel for long distances at incredible speed in a gig, taking very little luggage. If he reached an unfordable river he would either swim or propel himself across it on an inflated skin; and often arrived at his destination before the messengers whom he had sent ahead to announce his approach.

58. It is a disputable point which was the more remarkable when he went to war: his caution or his daring. He never exposed his army to ambushes, but made careful reconnaissances; and refrained from crossing over into Britain until he had collected reliable information (from Gaius Volusenus) about the harbours there, the best course to steer, and the navigational risks. On the other hand, when news reached him that his camp in Germany was being besieged, he disguised himself as a Gaul and picked his way through the enemy outposts to take command on the spot.

He ferried his troops across the Adriatic from Brindisi to Dyrrhachium in the winter season, running the blockade of Pompey's fleet. And one night, when Mark Antony had delayed the supply of reinforcements, despite repeated pleas, Caesar muffled his head with a cloak and secretly put to sea in a small boat, alone and incognito; forced the helmsman to steer into the teeth of a gale, and narrowly escaped shipwreck..

59. Religious scruples never deterred him for a moment. At the formal sacrifice before he launched his attack on Scipio and King Juba, the victim escaped; but he paid no heed to this most unlucky sign and marched off at once. He had also slipped and fallen as he disembarked on the coast of Africa, but turned an unfavourable omen into a favourable one by clasping the ground and shouting: 'Africa, I have tight hold of you!' Then, to ridicule the prophecy according to which it was the Scipios' fate to be perpetually victorious in Africa, he took about with him a contemptible member of the Cornelian branch of the Scipio family nicknamed 'Salvito' — or 'Greetings! but off with him! ' — the 'Greetings! ' being an acknowledgement of his distinguished birth, the 'Off with him!' a condemnation of his disgusting habits.

60. Sometimes he fought after careful tactical planning, sometimes on the spur of the moment — at the end of a march, often; or in miserable weather, when he would be least expected to make a move. Towards the end of his life, however, he took fewer chances; having come to the conclusion that his unbroken run of victories ought to sober him, now that he could not possibly gain more by winning yet another battle than he would lose by a defeat. It was his rule never to let enemy troops rally when he had routed them, and always therefore to assault their camp at once. If the fight were a hard-fought one he used to send the chargers away — his own among the first — as a warning that those who feared to stand their ground need not hope to escape on horseback.

61. This charger of his, an extraordinary animal with feet that looked almost human — each of its hoofs was cloven in five parts, resembling human toes — had been foaled on his private estate. When the soothsayers pronounced that its master would one day rule the world, Caesar carefully reared, and was the first to ride, the beast; nor would it allow anyone else to do so. Eventually he raised a statue to it before the Temple of Mother Venus.

62. If Caesar's troops gave ground he would often rally them in person, catching individual fugitives by the throat and forcing them round to face the enemy again; even if they were panic-stricken — as when one standard-bearer threatened him with the sharp butt of his Eagle and another, whom he tried to detain, ran off leaving the Eagle in his hand.

63. Caesar's reputation for presence of mind is fully borne out by the instances quoted. After Pharsalus, he had sent his legions ahead of him into Asia and was crossing the Hellespont in a small ferry-boat, when Lucius Cassius with ten naval vessels approached. Caesar made no attempt to escape but rowed towards the flagship and demanded Cassius's surrender; Cassius gave it and stepped aboard Caesar's craft.

64. Again, while attacking a bridge at Alexandria, Caesar was forced by a sudden enemy sortie to jump into a row-boat. So many of his men followed him that he dived into the sea and swam 200 yards until he reached the nearest Caesarean ship — holding his left hand above water the whole way to keep certain documents dry; and towing his purple cloak behind him with his teeth, to save this trophy from the Egyptians.

65. He judged his men by their fighting record, not by their morals or social position, treating them a11 with equal severity — and equal indulgence; since it was only in the presence of the enemy that he insisted on strict discipline. He never gave forewarning of a march or a battle, but kept his troops always on the alert for sudden orders to go wherever he directed. Often he made them turn out when there was no need at all, especially in wet weather or on public holidays. Sometimes he would say: 'Keep a close eye on me!' and then steal away from camp at any hour of the day or night, expecting them to follow. It was certain to be a particularly long march, and hard on stragglers.

66. If rumours about the enemy's strength were causing alarm, his practice was to heighten morale, not by denying or belittling the danger, but on the contrary by further exaggerating it. For instance, when his troops were in a panic before the battle of Thapsus at the news of King Juba's approach, he called them together and announced:

'You may take it from me that the King will be here within a few days, at the head of ten infantry legions, thirty thousand cavalry, a hundred thousand lightly armed troops, and three hundred elephants. This being the case, you may as well stop asking questions and making guesses. I have given you the facts, with which I am familiar. Any of you who remain unsatisfied will find themselves aboard a leaky hulk and being carried across the sea wherever the winds may decide to blow them.

67. Though turning a blind eye to much of their misbehaviour, and never laying down any fixed scale of penalties, he allowed no deserter or mutineer to escape severe punishment. Sometimes, if a victory had been complete enough, he relieved the troops of all military duties and let them carry on as wildly as they pleased. One of his boasts was: 'My men fight just as well when they are stinking of perfume.' He always addressed them not with 'My men', but with 'Comrades...', which put them into a better humour; and he equipped them splendidly. The silver and gold inlay of their weapons both improved their appearance on parade and made them more careful not to get disarmed in battle, these being objects of great value. Caesar loved his men dearly; when news came that Titurius's command had been massacred, he swore neither to cut his hair nor to trim his beard until they had been avenged.

68. By these means he won the devotion of his army as well as making it extraordinarily gallant. At the outbreak of the Civil War every centurion in every legion volunteered to equip a cavalryman from his savings; and the private soldiers unanimously offered to serve under him without pay or rations, pooling their money so that nobody should go short. Throughout the entire struggle not a single Caesarean deserted, and many of them, when taken prisoners, preferred death to the alternative of serving with the Pompeians. Such was their fortitude in facing starvation and other hardships, both as besiegers and as besieged, that when Pompey was shown at Dyrrhachium the substitute for bread, made of grass, on which they were feeding, he exclaimed: 'I am fighting wild beasts!' Then he ordered the loaf to be hidden at once, not wanting his men to find out how tough and resolute the enemy were, and so lose heart.

Here the Caesareans suffered their sole reverse, but proved their stout-heartedness by begging to be punished for the lapse; whereupon he felt called upon to console rather than upbraid them. In other battles, they beat enormously superior forces. Shortly before the defeat at Dyrrhachium, a single company of the Sixth Legion held a redoubt against four Pompeian legions, though almost every man had been wounded by arrow-shot — 130,000 arrows were afterwards collected on the scene of the engagement. This high level of courage is less surprising when individual examples are considered: for the centurion Cassius Scaeva, blinded in one eye, wounded in thigh and shoulder, and with no less than 120 holes in his shield, continued to defend the approaches to the redoubt. Nor was his by any means an exceptional case. At the naval battle of Marseilles, a private soldier named Gaius Acilius grasped the stern of an enemy ship and, when someone lopped off his right hand, nevertheless boarded her and drove the enemy back with the boss of his shield only — a feat rivalling that of the Athenian Cynaegeirus (brother of the poet Aeschylus), who showed similar courage when maimed in trying to detain a Persian ship after the victory at Marathon.

69. Caesar's men did not mutiny once during the Gallic War, which lasted thirteen years. In the Civil Wars they were less dependable, but whenever they made insubordinate demands he faced them boldly, and always brought them to heel again — not by appeasement but by sheer exercise of personal authority. At Piacenza, although Pompey's armies were as yet undefeated, he disbanded the entire Ninth Legion with ignominy, later recalling them to the Colours in response to their abject pleas; this with great reluctance and only after executing the ringleaders.

70. At Rome, too, when the Tenth Legion agitated for their discharge and bounty and were terrorizing the City, Caesar defied the advice of his friends and at once confronted the mutineers in person. Again he would have disbanded them ignominiously, though the African war was still being hotly fought; but by addressing them as 'Citizens' he readily regained their affections. A shout went up: 'We are your soldiers, Caesar, not civilians!' and they clamoured to serve under him in Africa: a demand which he nevertheless disdained to grant. He showed his contempt for the more disaffected soldiers by withholding a third part of the prize-money and land which had been set aside for them.

71. Even as a young man Caesar was well known for the loyalty he showed his dependants. While praetor in Africa, he protected a nobleman's son named Masintha against the tyranny of Hiempsal, King of Numidia; with such devotion that in the course of the quarrel he caught Juba, the Numidian heir-apparent, by the beard. Masintha, being then declared the King's vassal, was arrested; but Caesar immediately rescued him from the Numidian guards and harboured him in his own quarters for a long while. At the close of this praetorship Caesar sailed for Spain, taking Masintha with him. The lictors carrying their rods of office, and the crowds who had come to say goodbye, acted as a screen; nobody realized that Masintha was hidden in Caesar's litter.

72. He showed consistent affection to his friends. Gaius Oppius, travelling by his side once through a wild forest, suddenly fell sick; but Caesar insisted on his using the only shelter that offered — a woodcutter's hut, hardly large enough for a single occupant — while he and the rest of his staff slept outside on the bare ground. Having attained supreme power he raised some of his friends, including men of humble birth, to high office and brushed aside criticism by saying: 'If bandits and cut-throats had helped to defend my honour, I should have shown them gratitude in the same way.'

73. Yet, when given the chance, he would always cheerfully come to terms with his bitterest enemies. He supported Gaius Memmius's candidature for the consulship, though they had both spoken most damagingly against each other. When Gaius Calvus, after his cruel lampoons of Caesar, made a move towards reconciliation through mutual friends, Caesar met him more than half way by writing him a friendly letter. Valerius Catullus had also libelled him in his verse about Mamurra, yet Caesar, while admitting that these were a permanent blot on his name, accepted Catullus's apology and invited him to dinner that same afternoon, and never interrupted his friendship with Catullus's father.

74. Caesar was not naturally vindictive; and if he crucified the pirates who had held him to ransom, this was only because he had sworn in their presence to do so; and he first mercifully cut their throats. He could never bring himself to take vengeance on Cornelius Phagites, even though in his early days, while he was sick and a fugitive from Sulla, Corneiius had tracked him down night after night and demanded large sums of hush-money. On discovering that Philemon, his slave-secretary, had been induced to poison him, Caesar ordered a simple execution, without torture. When Publius Clodius was accused of adultery with Caesar's wife Pompeia, in sacrilegious circumstances, and both her mother-in-law Aurelia and her sister-in-law Julia had given the court a detailed and truthful account of the affair, Caesar himself refused to offer any evidence. The Court then asked him why, in that case, he had divorced Pompeia. He replied:

'Because I cannot have members of my household suspected, even if they are innocent.'

75. Nobody can deny that during the Civil War, and after, he behaved with wonderful restraint and clemency. Whereas Pompey declared that all who were not actively with him were against him and would be treated as public enemies, Caesar announced that all who were not actively against him were with him. He allowed every centurion whom he had appointed on Pompey's recommendation to join the Pompeian forces if he pleased. At Lerida, in Spain, the articles of capitulation were being discussed between Caesar and the Pompeian generals Afranius and Petreius, and the rival armies were fraternizing, when Afranius suddenly decided not to surrender and massacred every Caesarean soldier found in his camp. Yet after capturing both generals a few days later, Caesar could not bring himself to pay Afranius back in the same coin; but let him go free. During the battle of Pharsalus he shouted to his men: 'Spare your fellow Romans!' and then allowed them to save one enemy soldier apiece, whoever he might be. My researches show that not a single Pompeian was killed at Pharsalus, once the fighting had ended, except Afranius and Faustus and young Lucius Caesar. It is thought that not even these three fell victims to his vengeance, though Afranius and Faustus had taken up arms again after he had spared their lives, and Lucius Caesar had cruelly cut the throats of his famous relative's slaves and freedmen, even butchering the wild beasts brought by him to Rome for a public show! Eventually, towards the end of his career, Caesar invited back to Italy all exiles whom he had not yet pardoned, permitting them to hold magistracies and command armies; and went so far as to restore the statues of Sulla and Pompey, which the City crowds had thrown down and smashed. He also preferred to discourage rather than punish any plots against his life, or any slanders on his name. All that he would do when he detected such plots, or became aware of secret nocturnal meetings, was to announce openly that he knew about them. As for slanderers, he contented himself with warning them in public to keep their mouths shut; and good-naturedly took no action either against Aulus Caecina for his most libellous pamphlet or against Pitholaus for his scurrilous verses.