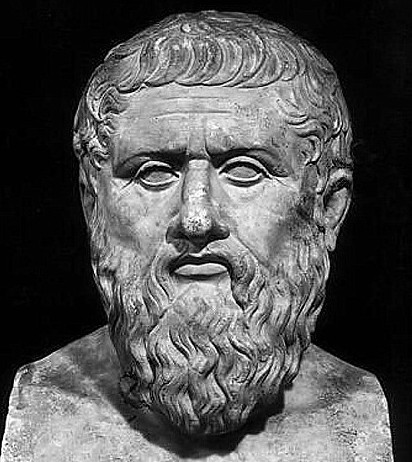

Plato in philosophy was a genuine innovator on a scale to which succeeding centuries offer no parallel. It may appear that, for many hundreds of years, the influence of Aristotle was more conspicuous and profound, but there is a sense in which this was not so: for Aristotle himself was, and usually spoke of himself as being, a Platonist — he owed far more, certainly, to Plato than Plato owed even to Socrates, whose influence upon him, though powerful, was limited in its scope. The range of Plato's own work was so immense that it is really impossible for an account of it to be both adequate and brief. There is not really to be found, among his numerous dialogues, any single "system" or set of doctrines that could be put forward as a final characterization of his position, and besides this Plato himself gives us to understand that his published writings do not embody all, or even the most important, of the doctrines that were actually taught in the Academy. A man's best thought, he seems to say, is likely to be, and even ought to be, reserved for living discussion in a limited circle of his followers and friends.

The best that can be done, then, for our present purpose is to identify in his writings certain recurrent or developing themes, with which it was characteristic of Plato to play, among an amazing range and richness of other interests, variations upon one or two central concerns.

We have seen already that the procedure of Socrates — the procedure by which, with constructive fervor and positive intent, he attacked the half-truths and muddled clichés of conventional thought — was a species of what has been called "dialectic." This notion of dialectic, of the "dialectical method," runs through very many of Plato's dialogues. But in the course of time it underwent much change and elaboration.

In the earliest dialogues — Charmides for instance, or Laches — not only is Socrates the leading dramatic character; he is also represented, as in later dialogues he is not, as proceeding in a manner that is quite clearly "Socratic." At this time, not long after the execution of Socrates, his influence on Plato's writings was still very strong; and indeed it is likely that many of the earlier dialogues were written specifically to record the contents and character of actual discussions with Socrates, who himself had left no writings behind him. Here, accordingly, "dialectic" is the dialectic of Socrates. The object of the inquiry is to establish a definition — of "temperance" in Charmides, of "courage" in Laches — and the procedure is to test (and overthrow) successive attempts and amended attempts at definition submitted by Socrates' more or less unwary interlocutors. Socrates' interest in definitions is attested by Aristotle; and here we see him in pursuit of definitions of (as it happens) certain ethical notions, refuting by a dexterous use of counter-examples the suggestions in which conventional unclarity found too ready expression.

Now there is a point which inevitably crops up in such discussions, reflection on which led Plato away from Socrates. A common mistake in attempting to frame a definition is to generalize too boldly from some particular instance of what is to be defined — to observe, for example, that religious people often go to church, and thence to conclude that religion can be defined as "churchgoing." Socrates doubtless was aware of this sort of mistake, and would have insisted that a distinction be drawn between the thing itself, and this or that particular instance of it — between courage, say, and this or that case of courageous conduct. But it appears that Plato — and not, apparently, Socrates — came to put upon this sort of distinction a special interpretation: he came to think that, apart from all the things and occurrences which make up the world of ordinary life, there must exist another realm of entities of a quite different sort — a realm of timeless, "intelligible" things of which "sensible" phenomena are merely the transitory instances, and of which definitions are, as it were, true descriptions. To these supposed things he gave the name Ideas, or Forms; and the resulting "Theory of Ideas" — which was in fact never one single theory nor finally worked out — was for very many years the heart of controversy in the Academy, and in the eyes of others the hallmark of Plato and his pupils.

The question at what precise stage, and to what extent, Plato came to think of his Forms as actually existing in a supersensible realm (not merely, that is, as instantiated in this world) is still a matter for some dispute. But this at least is clear: in quite early dialogues Plato speaks of ordinary objects as copies (always imperfect copies) of Forms, a way of speaking which plainly carries the implication that Forms and ordinary things have their separate existence and status.

The range of problems in the treatment of which Forms now appear is wide enough to show clearly why the theory was thought to be so important. We may mention some. It seems that Plato in his youth had been much impressed by the Heraclitean doctrine of "the flux," the view that in this world nothing is permanent or stable or at different times the same, and he had asked himself how, if this were so, knowledge was possible. What could be known to be true, if all things were perpetually changing? But now, it seemed, he was able to say that, though perhaps our ordinary world was a fleeting Heraclitean "river," yet there were Forms that did not change but existed in timeless perfection. Would these, then, not be the objects of true knowledge? Again, both on his own account and under the influence of Pythagoras, Plato was deeply interested in mathematics, which meant, at that time, predominantly geometry. Now when geometers spoke of the properties of "the square" or "the circle," to what were they referring? Not to their diagrams, nor to other particular squares or circles, for these were always imperfect. Must they not, then, be speaking of the Forms of "circle" or "square," non-sensible things having none of the imperfections found in their everyday "copies"?

A more ambitious employment of the theory occurs in the central books of Plato's most celebrated dialogue, The Republic. Here Forms are appealed to not only in the definition of knowledge, but in the definition of philosophy itself; in particular they introduce a new conception of "dialectical method". Plato is thinking here of the education of his "philosopher-kings," those possible rulers in whom his political pessimism had led him to look for the way out from the confusions of his age. He holds, first of all, that it is an essential first step to go beyond the assumptions, the "opinions," of everyday life. For all these, and for the character of the shifting, "unreal" world of daily experience, an "explanation" must be found in that real, timeless, and perfect realm in which Forms exist. But here he adds that Forms themselves are hierarchically ordered. Apprehension of some, those, for instance, of the mathematician, still leaves room for a question; some further "explanation" is called for. And in a famous passage he avers that the Form of the Good is the single and sufficient goal of dialectical inquiry. It is here, and here only, that the constant search after reasons can find a satisfactory terminus. If once a man could clearly and fully apprehend the Form of the Good, then he would see exactly why all else should be as it is. He speaks almost, at times, as if the Form of the Good were actually the creator and controller of all other things, and in that sense essential to their explanation. But he does not profess, either here or in any other dialogue, to have attained for himself this ultimate and sufficient insight; and though he says here that its achievement is the purpose of "dialectic," the essential purpose of the philosopher, he says little in detail — perhaps he had little to say — of the actual method by which that purpose is to be pursued.

All this, it may be thought, has much of the character of a visionary mysticism. But Plato, for all the intensity of his imagination, was a true philosopher, never satisfied with half-formulations or unargued assertion. It seems quite clear that he never regarded the Theory of Ideas as a final solution, but rather as a fertile topic for further inquiry. In later years he revised, according to Aristotle's testimony, the account of mathematics to which that theory had led him. The definition of knowledge he actually reconsidered in a dialogue, Theaetetus, which makes no mention of the theory whatever. And constantly he returned, in his Parmenides and elsewhere, to the grave difficulties involved in his "objectification" of the Forms — to the problems of how such objects, if objects they were, could be related to the objects of the ordinary world, and to each other. Although his theory was for many years at the center of the Academy's researches, it was never allowed to put an end to inquiry; "dialectic" in Socrates' sense always continued, and no doctrine was deemed to be exempt from scrutiny and objection. Plato's own conception of dialectic underwent one further transformation which must briefly be described. His new idea, foreshadowed in the Phaedrus quite soon after the composition of the Republic, is perhaps best stated in the later Philebus. Plato there says:

"There neither is nor ever will be a better than my own favorite way, which has nevertheless often deserted me and left me helpless in the hour of need. . . . It is the parent of all the discoveries in the arts. . . . We ought, in every inquiry, to begin by laying down one Form of that which is the object of inquiry; this unity we shall find in everything. Having found it, we may next proceed to look for two, if there be two, or, if not, then for three or some other number, subdividing each of these units, until at last the unity with which we began is seen not only to be one and many and an infinity of things, but also a definite number; we must not attribute infinity to the many until the entire number of the species intermediate between unity and infinity has been discovered. . . ."

This, he now holds, is the proper procedure of dialectic .

It may seem that the idea behind these rather strange words is an unexciting one: essentially, Plato seems to be proposing a program of definition per genus et differentiam , a mere method of orderly classification. It must be remembered, however, that the logical insight expressed in this procedure was then wholly new. Moreover, Plato believed in the possibility of discovering (or constructing) by resolute use of this method a kind of map of the world of Forms, or perhaps rather a kind of genealogical table in which all would appear with their proper degrees of subordination. He may have thought at one time of the Good as the highest genus , as it were the ancestor of all the rest. Later (his interest shifting from ethics and politics to logic) he considered the claims of Existence, Sameness, and Difference. Still later the Form of Unity was given pride of place. But in fact, quite apart from the interest or lack of interest of Plato's own applications of this "dialectical method" in his inquiries into Forms and their interrelations, there proved to be great value in his idea for those who were embarking upon strictly scientific researches. All sciences, it has been said, must begin with classification. And the many studies in natural history which were organized by Aristotle owed much of their method to this latest development by Plato of "dialectic."

It would be impossible, while remaining within the scope of the present book, to give any adequate presentation in Plato's own words of the ideas roughly sketched out above; for that the reader must be referred elsewhere. However, some notion of the intensity with which his views were felt and expounded can be derived from his famous and haunting image of "the Cave" — from that passage in Book VII of the Republic in which he seeks to make the reader grasp the full significance of progressive philosophical enlightenment; unless, he implies, we can progress in this direction, we remain in the Cave, the home of illusion and error, with, accordingly, no notion of the good life for ourselves and others, and thence no hope of bringing order into a distracted world.

"Next, then," I said, "take the following parable of education and ignorance as a picture of the condition of our nature. Imagine mankind as dwelling in an underground cave with a long entrance open to the light across the whole width of the cave; in this they have been from childhood, with necks and; legs fettered, so they have to stay where they are. They cannot move their heads round because of the fetters, and they can only look forward, but light comes to them from fire burning behind them higher up at a distance. Between the fire and the prisoners is a road above their level, and along it imagine a, low wall has been built, as puppet showmen have screens in, front of their people over which they work their puppets."

"I see," he said.

"See, then, bearers carrying along this wall all sorts of articles which they hold projecting above the wall, statues of men and other living things, made of stone or wood and all kinds of stuff, some of the bearers speaking and some silent, as you might expect."

"What a remarkable image," he said, "and what remarkable prisoners!"

"Just like ourselves," I said. "For, first of all, tell me this: What do you think such people would have seen of themselves and each other except their shadows, which the fire cast on the opposite wall of the cave?"

"I don't see how they could see anything else," said he, "if they were compelled to keep their heads unmoving all their lives!"

"Very well, what of the things being carried along? Would not this be the same?"

"Of course it would."

"Suppose the prisoners were able to talk together, don't you think that when they named the shadows which they saw passing they would believe they were naming things?"'

"Necessarily."

"Then if their prison had an echo from the opposite wall, whenever one of the passing bearers uttered a sound, would they not suppose that the passing shadow must be making the sound? Don't you think so?"

"Indeed I do," he said.

"If so," said I, "such persons would certainly believe that there were no realities except those shadows of handmade things."

"So it must be," said he.

"Which they had never seen. They would say 'tree' when it was only a shadow of the model of a tree.

"Now consider," said I, "what their release would be like, and their cure from these fetters and their folly; let us imagine whether it might naturally be something like this. One might be released, and compelled suddenly to stand up and turn his neck round, and to walk and look towards the firelight; all this would hurt him, and he would be too much dazzled to see distinctly those things whose shadows he had seen before. What do you think he would say, if someone told him that what he saw before was foolery, but now he saw more rightly, being a bit nearer reality and turned towards what was a little more real? What if he were shown each of the passing things, and compelled by questions to answer what each one was? Don't you think he would be puzzled, and believe what he saw before was more true than what was shown to him now?"

"Far more," he said.

"Then suppose he were compelled to look towards the real light, it would hurt his eyes, and he would escape by turning them away to the things which he was able to look at, and these he would believe to be clearer than what was being shown to him."

"Just so," said he.

"Suppose, now," said I, "that someone should drag him thence by force, up the rough ascent, the steep way up, and never stop until he could drag him out into the light of the sun, would he not be distressed and furious at being dragged; and when he came into the light, the brilliance would fill his eyes and he would not be able to see even one of the things now called real?"'

"That he would not," said he, "all of a sudden."

"He would have to get used to it, surely, I think, if he is to see the things above. First he would most easily look at shadows, after that images of mankind and the rest in water, lastly the things themselves. After this he would find it easier to survey by night the heavens themselves and all that is in them, gazing at the light of the stars and moon, rather than by day the sun and the sun's light."

"Of course."

"Last of all, I suppose, the sun; he could look on the sun itself by itself in its own place, and see what it is like, not reflections of it in water or as it appears in some alien setting."

"Necessarily," said he.

"And only after all this he might reason about it, how this is he who provides seasons and years, and is set over all there is in the visible region, and he is in a manner the cause of all things which they saw."

"Yes, it is clear," said he, "that after all that, he would come to this last."

"Very good. Let him be reminded of his first habitation, and what was wisdom in that place, and of his fellow-prisoners there; don't you think he would bless himself for the change, and pity them?"

"Yes, indeed."

"And if there were honours and praises among them and prizes for the one who saw the passing things most sharply and remembered best which of them used to come before and which after and which together, and from these was best able to prophesy accordingly what was going to come — do you believe he would set his desire on that, and envy those who were honoured men or potentates among them? Would he not feel as Homer says, and heartily desire rather to be serf of some landless man on earth and to endure anything in the world, rather than to opine as they did and to live in that way?"

"Yes indeed," said he, "he would rather accept anything than live like that."

"Then again," I said, "just consider; if such a one should go down again and sit on his old seat, would he not get his eyes full of darkness coming in suddenly out of the sun?"

"Very much so," said he.

"And if he should have to compete with those who had been always prisoners, by laying down the law about those shadows while he was blinking before his eyes were settled down — and it would take a good long time to get used to things — wouldn't they all laugh at him and say he had spoiled his eyesight by going up there, and it was not worthwhile so much as to try to go up? And would they not kill anyone who tried to release them and take them up, if they could somehow lay hands on him and kill him?"'

"That they would!" said he.

"Then we must apply this image, my dear Glaucon," said I, "to all we have been saying. The world of our sight is like the habitation in prison, the firelight there to the sunlight here, the ascent and the view of the upper world is the rising of the soul into the world of mind; put it so and you will not be far from my own surmise, since that is what you want to hear; but God knows if it is really true. At least, what appears to me is, that in the world of the known, last of all,' is the idea of the good, and with what toil to be seen! And seen, this must be inferred to be the cause of all right and beautiful things for all, which gives birth to light and the king of light in the world of sight, and, in the world of mind, herself the queen produces truth and reason; and she must be seen by one who is to act with reason publicly or privately."

"I believe as you do," he said, "in so far as I am able."

"Then believe also, as I do," said I, "and do not be surprised, that those who come thither are not willing to have part in the affairs of men, but their souls ever strive to remain above; for that surely may be expected if our parable fits the case."

"Quite so," he said.

"Well then," said I, "do you think it surprising if one leaving divine contemplations and passing to the evils of men is awkward and appears to be a great fool, while he is still blinking — not yet accustomed to the darkness around him, but compelled to struggle in law courts or elsewhere about shadows of justice, or the images which make the shadows, and to quarrel about notions of justice in those who have never seen justice itself?"

"Not surprising at all," said he.

"But any man of sense," I said, "would remember that the eyes are doubly confused from two different causes, both in passing from light to darkness and from darkness to light; and believing that the same things happen with regard to the soul also, whenever he sees a soul confused and unable to discern anything he would not just laugh carelessly; he would examine whether it had come out of a more brilliant life, and if it were darkened by the strangeness; or whether it had come out of greater ignorance into a more brilliant light, and if it were dazzled with the brighter illumination. Then only would he congratulate the one soul upon its happy experience and way of life, and pity the other; but if he must laugh, his laugh would be a less downright laugh than his laughter at the soul which came out of the light above."

"That is fairly put," said he.

"Then if this is true," I said, "our belief about these matters must be this, that the nature of education is not really such as some of its professors say it is; as you know, they say that there is not understanding in the soul, but they put it in, as if they were putting sight into blind eyes."

"They do say so," said he.

"But our reasoning indicates," I said, "that this power is already in the soul of each, and is the instrument by which each learns; thus if the eye could not see without being turned with the whole body from the dark towards the light, so this instrument must be turned round with the whole soul away from the world of becoming until it is able to endure the sight of being and the most brilliant light of being: and this we say is the good, don't we?"

"Yes."

"Then this instrument," said I, "must have its own art, for the circumturning or conversion, to show how the turn can be most easily and successfully made; not an art of putting sight into an eye, which we say has it already, but since the instrument has not been turned aright and does not look where it ought to look — that's what must be managed."

"So it seems," he said.

"Now most of the virtues which are said to belong to the soul are really something near to those of the body; for in fact they are not already there, but they are put later into it by habits and practices; but the virtue of understanding everything really belongs to something certainly more divine, as it seems, for it never loses its power, but becomes useful and helpful or, again, useless and harmful, by the direction in which it is turned. Have you not noticed men who are called worthless but clever, and how keen and sharp is the sight of their petty soul, and how it sees through the things towards which it is turned? Its sight is clear enough, but it is compelled to be the servant of vice, so that the clearer it sees the more evil it does."

"Certainly," said he.

"Yet if this part of such a nature," said I, "had been hammered at from childhood, and all those leaden weights of the world of becoming knocked off — the weights, I mean, which grow into the soul from gorging and gluttony and such pleasures, and twist the soul's eye downwards — if, I say, it had shaken these off and been turned round towards what is real and true, that same instrument of those same men would have seen those higher things most clearly, just as now it sees those towards which it is turned."

"Quite likely," said he.

"Very well," said I, "isn't it equally likely, indeed, necessary, after what has been said, that men uneducated and without experience of truth could never properly supervise a city, nor can those who are allowed to spend all their lives in education right to the end? The first have no single object in life, which they must always aim at in doing everything they do, public or private; the second will never do anything if they can help it, believing they have already found mansions abroad in the Islands of the Blest."

"True," said he.

"Then it is the task of us founders," I said, "to compel the best natures to attain that learning which we said was the greatest, both to see the good, and to ascend that ascent; and when they have ascended and properly seen, we must never allow them what is allowed now."

"What is that, pray?" he asked.

"To stay there," I said, "and not be willing to descend again to those prisoners, and to share their troubles and their honours, whether they are worth having or not."

"What!" said he, "are we to wrong them and make them live badly, when they might live better?"

"You have forgotten again, my friend," said I, "that the law is not concerned how any one class in a city is to prosper above the rest; it tries to contrive prosperity in the city as a whole, fitting the citizens into a pattern by persuasion and compulsion, making them give of their help to one another wherever each class is able to help the community. The law itself creates men like this in the city, not in order to allow each one to turn by any way he likes, but in order to use them itself to the full for binding the city together."

"True," said he, "I did forget."

"Notice then, Glaucon," I said, "we shall not wrong the philosophers who grow up among us, but we shall treat them fairly when we compel them to add to their duties the care and guardianship of the other people. We shall tell them that those who grow up philosophers in other cities have reason in taking no part in public labours there; for they grow up there of themselves, though none of the' city governments wants them; a wild growth has its rights, it owes nurture to no one, and need not trouble to pay anyone for its food. But you we have engendered, like king bees' in hives, as leaders and kings over yourselves and the rest of the city; you have been better and more perfectly educated than the others, and are better able to share in both ways of life. Down you must go then, in turn, to the habitation of the others, and accustom yourselves to their darkness; for when you have grown accustomed you will see a thousand times better than those who live there, and you will know what the images are and what they are images of, because you have seen the realities behind just and beautiful and good things. And so our city will be managed wide awake for us and for you, not in a dream, as most are now, by people fighting together for shadows, and quarrelling to be rulers, as if that were a great good. But the truth is more or less that the city where those who are to rule are least anxious to be rulers is of necessity best managed and has least faction in it; while the city which gets rulers who want it most is worst managed."

"Certainly," said he.

"Then will our fosterlings disobey us when they hear this? Will they refuse to help, each group in its turn, in the labours of the city, and want to spend most of their time dwelling in the pure air?"

"Impossible," said he, "for we shall only be laying just commands on just men. No, but undoubtedly each man of them will go to the ruler's place as to a grim necessity, exactly the opposite of those who now rule in cities."

"For the truth is, my friend," I said, "that only if you can find for your future rulers a way of life better than ruling, is it possible for you to have a well-managed city; since in that city alone those will rule who are truly rich, not rich in gold, but in that which is necessary for a happy man, the riches of a good and wise life: but if beggared and hungry, for want of goods of their own, they hasten to public affairs, thinking that they must snatch goods for themselves from there, it is not possible. Then rule becomes a thing to be fought for; and a war of such a kind, being between citizens and within them, destroys both them and the rest of the city also."

"Most true," said he.

"Well, then," said I, "have you any other life despising political office except the life of true philosophy?"

"No, by heaven," said he.

"But again," said I, "they must not go awooing office like so many lovers! If they do, their rival lovers will fight them."

"Of course they will!"

"Then what persons will you compel to accept guardianship of the city other than those who are wisest in the things which enable a city to be best managed, who also have honours of another kind and a life better than the political life?"

"No others," he answered.

By way of further illustration of Plato's work, it has seemed best not to assemble a collection of disconnected fragments, but rather to present, of some single dialogue, a large enough proportion to give room for real argument to develop. For this purpose the Meno seems particularly suitable. It belongs to the earlier group of Plato's writings, and is more "Socratic" both in form and content than the later dialogues are. It lies close, however, to the heart of Plato's own interests; in many ways it is an ideal introduction to the Republic, in which the question raised here — What is virtue, and can it be taught? — is given an answer more positive than Plato could offer at this stage. It has the advantage, too, of being in itself perfectly clear, and therefore not in need of explanation and commentary; nor does it raise questions in those parts of Plato's philosophy, full discussion of which would be impossible in present limits.

Although there is no good reason to suppose that such a conversation as this between Menon and Socrates ever actually occurred, that supposition would not be impossible. We learn from Xenophon that Menon, of a distinguished Thessalian family, took part in the campaign of Cyrus the younger against his brother Artaxerxes in 401 B.C.; and he might have been in Athens in, say, the previous year — a few years, that is, before the death of Socrates, and indeed at a time when Plato too could have been present. Xenophon speaks of Menon very unfavorably; Plato represents him in this dialogue only as being somewhat impatient, and in particular as being too easily impressed by the sophists. It is a curious point that the later part of the dialogue brings Anytos into the conversation; for it was Anytos who, a few years later than the fictional date of the discussion, brought the charges which resulted in Socrates' execution. Plato was actually writing, of course, after this event; the sharp warning to Socrates with which Anytos departs is a dramatic device, not a piece of inspired fore-sight. But in view of this it is all the more striking that he should write of Anytos, as he does, with moderation, and even charity. Perhaps this implies that he bore against Anytos no personal resentment, feeling that, so long as the true basis of good conduct was undiscovered, individual wrongdoers were not too much to be blamed.

The dialogue opens abruptly:

MENON: Can you tell me, Socrates — can virtue be taught? Or if not, does it come by practice? Or does it come neither by practice nor by teaching, but do people get it by nature, or in some other way?

SOCRATES: My dear Menon, the Thessalians have always had a good name in our nation — they were always admired as. good horsemen and men with full purses. Now, it seems to me, we must add brains to the list. Your friend Aristippos is a very good example, and his townsmen from Larissa. Gorgias is the man who set it all going. As soon as he got there, all the Aleuadai were at his feet — your own bosom friend Aristippos was one — not to mention the rest of Thessaly. Here's a custom he taught you, at least — to answer generously and without fear if anyone asked you a question; quite natural, of course, when one knows the answer. Just what he did himself; he was a willing victim of the civilized world of Hellas — any Hellene might ask him anything he liked, and every mortal soul got his answer!

But here, my dear Menon, it is just the opposite. There is a regular famine of brains here, and your part of the world seems to hold a monopoly in that article. At least, if you do ask anyone here a question like that, all you will get is a laugh and — "My good man, you must think I am inspired! Virtue? Can it be taught? Or how does it come? Do I know that? So far from knowing whether it can be taught or can't be taught, I don't know even the least little thing about virtue, I don't even know what virtue is!"

I'm in the same fix myself, Menon. I am as poor of the article as the rest of us, and I have to blame myself that I don't know the least little thing about virtue, and when I don't know what a thing is, how can I know its quality? Take Menon, for example: If someone doesn't know in the least who Menon is, how can he know whether Menon is handsome or rich or even a gentleman, or perhaps just the opposite? Do you think he can?

MENON: Not I. But look here, Socrates, don't you really know what virtue is? Are we to give that report of you in Larissa?

SOCRATES: Just so, my friend, and more — I never met any — one who did, so far as I know.

MENON: What! Did not you meet Gorgias when he was here?

SOCRATES: Oh, yes.

MENON: Didn't you think he knew?

SOCRATES: I have rather a poor memory, Menon, so I can't say at the moment whether I did think so. But perhaps he did know, or perhaps you know what he said: kindly remind me, then, what he did say. You say it yourself, if you like; for I suppose you think as he thought.

MENON: Oh, yes.

SOCRATES: Then let us leave him out of it, since he is not here; tell me yourself, in heaven's name, Menon, what do you say virtue is? Tell me, and don't grudge it; it will be the luckiest lie I ever told if it turns out that you know and Gorgias knew, and I went and said I never met anyone who did know.

MENON: That is nothing difficult, my dear Socrates. First, if you like, a man's virtue, that is easy; this is a man's virtue: to be able to manage public business, and in doing it to help friends and hurt enemies, and to take care to keep clear of such mischief himself. Or, if you like, a woman's virtue, there's no difficulty there: she must manage the house well, and keep the stores all safe, and obey her husband. And a child's virtue is different for boy and girl, and an older man's, a freeman's, if you like, or a slave's, if you like. There are a very large number of other virtues, so there is no difficulty in saying what virtue is; for according to each of our activities and ages each of us has his virtue for doing each sort of work, and in the same way, Socrates, I think, his vice.

SOCRATES: I seem to have been lucky indeed, my dear Menon, if I have been looking for one virtue and found a whole swarm of virtues in your store. However, let us take up this image, Menon, the swarm. If I asked you what a bee really is, and you answered that there are many different kinds of bees, what would you answer me if I asked you then: "Do you say there are many different kinds of bees, differing from each other in being bees more or less? Or do they differ in some other respect, for example in size, or beauty, and so forth?" Tell me, how would you answer that question?

MENON: I should say that they are not different at all one from another in beehood.

SOCRATES: Suppose I went on to ask: "Tell me this, then — what do you say exactly is that in which they all are the same, and not different?" Could you answer anything to that?

MENON: Oh, yes.

SOCRATES: Very well, now then for virtues. Even if there are many different kinds of them, they all have one something, the same in all, which makes them virtues. So if one is asked, "What is virtue?" one must have this clear in his view before he can answer the question. Do you understand what I mean?

MENON: I think I understand; but I do not yet grasp your question as I could wish.

SOCRATES: Do you think that virtue alone is like that, Menon — I mean one thing in a man and another in a woman, and so forth, or do you also say the same of health and size and strength? Do you think health is one thing in a man, and , another in a woman? Or is the essence the same everywhere if it be health, whether it be in a man or in anything else whatever?

MENON: I think health is the same thing in both man and woman.

SOCRATES: And what of size and strength? If a woman is strong, is it the same essence and the same strength which will make her strong? By the same strength I mean this: the strength is not different in itself whether it be in a man or a woman. Do you think there is any difference?

MENON: Why, no.

SOCRATES: Yet virtue will differ in itself in a boy and in an old man, in a woman and in a man?

MENON: I can't help thinking, Socrates, that this is not quite like those other things.

SOCRATES: Very well: Did you not say that man's virtue is to manage public affairs well, and woman's to manage a home?

MENON: Yes, I did.

SOCRATES: Then is it possible to manage a state or a house or anything well, without managing temperately and justly?

MENON: Certainly not.

SOCRATES: If, then, they manage temperately and justly, they will manage with temperance and justice?

MENON: Necessarily.

SOCRATES: Then both need the same things, if they are to be good, both woman and man — justice and temperance.

MENON: So it seems.

SOCRATES: : What of the boy and the old man? If they are reckless and unjust, could they ever be good?

MENON: Certainly not.

SOCRATES: But they must be temperate and just?

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: Then all men are good in the same way? For when they have the same things, they are good.

MENON: So it seems.

SOCRATES: : Then I suppose if they had not the same virtue, they would not be good in the same way.

MENON: Certainly not.

SOCRATES: Since therefore the same virtue is in all, try to tell me, and try to remember, what Gorgias says it is, and what you say too.

MENON: What can it be but to be able to rule men? If you want something which is the same in all.

SOCRATES: That is just what I do want. But is it the same virtue in a boy, Menon, and a slave, for each of them to be able to rule his master? And do you think he that ruled would still be a slave?

MENON: No, Socrates, I certainly don't think that.

SOCRATES: For it isn't reasonable, my good fellow. But here is another thing to consider. You say, "able to rule": shall we not add to it justly, not unjustly?

MENON: I think so, yes; for justice is virtue, Socrates.

SOCRATES: Virtue, Menon, or a virtue?

MENON: What do you mean by that?

SOCRATES: The same as in anything else. For example, if you please, take roundness: this I would say is a figure, not simply thus — figure. I would say so because there are other figures.

MENON: What you said was quite right, since I agree that there are other virtues besides justice.

SOCRATES: What are they, tell me, just as I would tell you other figures if you ask; then you tell me some other virtues.

MENON: Very well. Courage, I think, is a virtue and temperance and wisdom and high-mindedness and plenty more.

SOCRATES: Here we are again, Menon: We looked for one virtue and found many, although that was in another way; but the one that is in all these things we cannot find! . . .

MENON: Then, my dear Socrates, virtue seems to me to be, as the poet says, "to rejoice in what is handsome and to be able"; I agree with the poet, and I say virtue is to desire handsome things and to be able to provide them.

SOCRATES: Do you say that the man who desires handsome things is desirous of good things?

MENON: By all means.

SOCRATES: Do you imply that there are some that desire bad things, and others good? Don't you think, my dear fellow, that all desire good things?

MENON: No, I don't.

SOCRATES: But some desire bad things?

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: Thinking the bad things to be good, you mean, or even recognising that they are bad, still they desire them?

MENON: Both, I think.

SOCRATES: Do you really think, my dear Menon, that anyone, knowing the bad things to be bad, still desires them?

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: What does he desire, do you say — to have them?

MENON: To have them; what else?

SOCRATES: Thinking that the bad things benefit him that has them, or knowing that they injure whoever gets them?

MENON: Some thinking that the bad things benefit, some also knowing that they injure.

SOCRATES: Do those who think that the bad things benefit know that the bad things are bad?

MENON: I don't think that at all.

SOCRATES: Then it is plain that those who desire bad things are those who don't know what they are, but they desire what they thought were good whereas they really are bad; so those who do not know what they are, but think they are good, clearly desire the good. Is not that so?

MENON: It really seems like it.

SOCRATES: Very well. Those who desire the bad things, as you say, but yet think that bad things injure whoever gets them, know, I suppose, that they themselves will be injured by them?

MENON: They must.

SOCRATES: But do not these believe that those who are inured are miserable in so far as they are injured?

MENON: They must believe that too.

SOCRATES: Miserable means wretched?

MENON: So I think.

SOCRATES: Well, is there anyone who wishes to be miserable and wretched?

MENON: I think not, Socrates.

SOCRATES: Then nobody desires bad things, my dear Menon, nobody, unless he wishes to be like that. For what is the depth of misery other than to desire bad things and to get them?

MENON: It really seems that is the truth, Socrates, and no one desires what is bad.

SOCRATES: You said just now, didn't you, that virtue is to desire good things and to be able to provide them.

MENON: Yes, I did.

SOCRATES: Well, one part of what you said, the desiring, is in all, and in this respect one man is no better than another.

MENON: It seems so.

SOCRATES: It is clear, then, that if one is better than another, he must be better in the ability.

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: Then according to your argument virtue is the power to get good things.

MENON: My dear Socrates, the whole thing, I must admit, seems to be exactly as you take it.

SOCRATES: Now let us see whether your last is true — perhaps you might be right. You say virtue is to be able to provide the good?

MENON: Quite so.

SOCRATES: Don't you call good such things as health and wealth?

MENON: Yes, and to possess gold and silver and public honour and appointments.

SOCRATES: Don't you say some other things are good besides these?

MENON: No, at least, I mean all such things as those.

SOCRATES: Very well; to provide gold and silver is virtue, according to Menon, the family friend of the Great King. Do you add to your providing, my dear Menon, the qualification "fairly and justly"? Or does that make no difference to you, and if a man provides them unjustly, you call it virtue all the same?

MENON: Oh dear me no, Socrates.

SOCRATES: It is vice then.

MENON: Dear me, yes, of course.

SOCRATES: It is necessary then, as it seems, to add to this getting, justice or temperance or piety or some other bit of virtue; or else it will not be virtue, although it provides good things.

MENON: Why, how could it be virtue without these?

SOCRATES: And not to get gold and silver when that is not just, neither for yourself nor anyone, is not this not-getting also virtue?

MENON: It looks like it.

SOCRATES: Then the getting of such good things would not be virtue any more than the not-getting; but as it seems, getting with justice would be virtue, and getting without such qualifications, vice.

MENON: I think it must be as you put it.

SOCRATES: Now we said a little while ago that each of them is a bit of virtue, justice and temperance and all things like that.

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: Then are you making fun of me, Menon?

MENON: How so, Socrates?

SOCRATES: Because I begged you just now not to break virtue into bits, or give me virtue as a handful of small change, and I gave you specimens to show how you ought to answer; and you simply paid no attention — now you tell me virtue is to be he able to get good things with justice, and justice, you say, is a bit of virtue!

MENON: Yes, that is what I say.

SOCRATES: It follows, then, from what you agree, that to do whatever we do along with a bit of virtue is virtue; for you say justice is a bit of virtue, and so with each of those bits. Well, why do I say this? Because when I begged you to tell me what whole virtue is, instead of telling me that (far from it!) you say that every action is virtue if it be done with a bit of virtue, just as if you had explained what virtue is as a whole and I should know it at once even if you chopped your coin up into farthings. Then I must put the very same question from the beginning, as it seems: My dear friend Menon, what is virtue, if a little bit of virtue would make any action virtue? For that is as much as saying, whenever anyone says it, that all action with justice is virtue. Don't you think yourself that I must put the same question again, or do you believe that we can know what a bit of virtue is, when we do not know virtue itself? . . .

MENON: By all means. However, my dear friend, I should very much like to consider and to hear what I began by asking, whether we ought to tackle what virtue is as being something which can be taught, or as if men get it by nature or in some other way.

SOCRATES: But if I were your master, Menon, as well as master of myself, we should not consider beforehand whether virtue can be taught or not until we had tried to find out first what virtue really is. But since you make no attempt to master yourself — I suppose you want to be a free man — but you do attempt to master me, and you do master me! I will give way to you — for what else am I to do? — and it seems we must consider what qualities a thing has when we don't know yet what it is. Please relax at least one little tittle of your mastery, and give way so far that we may use a hypothesis to work from, in considering whether it can come by teaching or in some other way. I mean by hypothesis what the geometricians often envisage, a standing ground to start from; when they are asked, for instance, about a space, "Is it possible to inscribe this triangular space in this circle?" They will say, "I don't know yet whether it can be done, but I think I have, one may say, a useful hypothesis to start from, such as this: If the space is such that when you apply it to the given line of the circle, it is deficient by a space of the same size as that which has been applied, one thing appears to follow, and if this be impossible, another. I wish, then, to make a hypothesis before telling you what will happen about the inscribing of it in the circle, whether that be possible or not."

There now, let us take virtue in that way. Since we don't know what it is or what it is like, let us make our hypothesis or ground to stand on, and then consider whether it can be taught or not. We proceed as follows: If virtue is a quality among the things which are about the soul, would virtue be teachable, or not? First, if it is like or unlike knowledge, can it be taught or not, or as we said just now, can it be remembered — we need not worry which name we use-but can it be taught? Or is it plain to everyone that only one thing is taught to men, and that is knowledge?

MENON: So it seems to me at least.

SOCRATES: Then if virtue is a knowledge, it is plain that it could be taught.

MENON: Of course.

SOCRATES: We have soon done with that — if it is such, it can be taught, if not such, not.

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: Now we have to consider, as it seems, whether virtue is a knowledge or something distinct from knowledge.

MENON: Agreed, that must be considered next.

SOCRATES: Very well. Don't we say that virtue is a good thing? This hypothesis holds for us, that it is good?

MENON: We do say so.

SOCRATES: Then if there is something good, and yet separate from knowledge, possibly virtue would not be a knowledge, but if there is no good which knowledge does not contain, it would be a right notion to suspect that it is a knowledge.

MENON: That is true.

SOCRATES: Further, by virtue we are good? ;

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: And if good, helpful; for all good things are helpful. Are they not?

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: And virtue, therefore, is helpful?

MENON: That must follow from what we have agreed.

SOCRATES: Let us consider then, taking up one by one, what sorts of things are helpful to us. Health, we say, and strength, and good looks, and wealth, of course; these and things like these we say are helpful, eh?

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: And these same things we say do harm sometimes also; do you agree with that?

MENON: I do.

SOCRATES: Consider then what leads each of these when it is helpful to us, and what leads each when it does harm. Are they not helpful when led by right use, and harmful when they are not?

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: Let us pass on then, and consider the things that concern the soul. You speak of temperance and justice and courage and cleverness at learning, and memory and high_ mindedness, and all such things?

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: Look now; such of these as seem to you to be not knowledge but different from knowledge, are they not sometimes harmful and sometimes helpful? For example courage, if courage is not intelligence but something like boldness; is it not true that when a man is bold without sense, he is harmed, but when with sense, he is helped?

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: Is it not the same with temperance and cleverness at learning? When things learnt are accompanied by sense and are fitted in their proper places they are helpful; without sense, harmful?

MENON: Very much so.

SOCRATES: Then, in short, all the stirrings and endurings of the soul, when wisdom leads, come to happiness in the end, but when senselessness leads, to the opposite?

MENON: So it seems.

SOCRATES: Then if virtue is one of the things in the soul, and if it must necessarily be helpful, it must be wisdom: since quite by themselves all the things about the soul are neither helpful nor harmful, but they become helpful or harmful by the addition of wisdom or senselessness. According to this argument, virtue, since it is helpful, must be some kind of wisdom.

MENON: I think so.

SOCRATES: Very well then, come now to the other things we mentioned a while since, wealth and so forth, and said they were sometimes good and sometimes harmful. When wisdom led any soul it made the things of the soul helpful, didn't it, and senselessness made them harmful: so also with these, the soul makes them helpful when it uses them rightly and leads them rightly, but harmful when not rightly?

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: The sensible soul leads them rightly, the senseless wrongly?

MENON: That is true.

SOCRATES: Then cannot we say this as a general rule: In man everything else depends on the soul; but the things of the soul itself depend on wisdom, if it is to be good; and so by this argument the helpful would be wisdom — and we say virtue is helpful.

MENON: We do.

SOCRATES: Then we say virtue is wisdom, either in whole in part?

MENON: I think what we say is well said, Socrates.

SOCRATES: Then if this is right, nature would not make men good.

MENON: I think not.

SOCRATES: Here is another thing surely: If good men were good by nature, we should have persons who could distinguish those young ones who were good in their nature, and we might take them over as they were indicated and keep them safe in the acropolis, and hallmark them more carefully than fine gold, that no one might corrupt them, but that when they grew up they should be useful to their cities.

MENON: Quite likely that, Socrates.

SOCRATES: Then since the good are not good by nature, is it by learning?

MENON: I really think that must be so; and it is plain, my dear Socrates, according to the hypothesis, that if virtue is knowledge, it can be taught.

SOCRATES: Yes, by Zeus, perhaps, but what if we were wrong in admitting that?

MENON: Well, it did seem just then to be a right conclusion.

SOCRATES: But what if we ought not to have agreed that it was right enough for then only, but for now also and all future time, if it is to be sound?

MENON: Why, what now? What makes you dissatisfied and distrustful? Do you think virtue is not knowledge?

SOCRATES: I will tell you Menon. It can be taught if it is knowledge; I do not wish to dispute the truth of that statement. But Y have my doubts whether it is knowledge; pray consider if there is any reason in that. Just look here: If a thing can be taught — anything, not virtue only — must there not be both teachers and learners of it?

MENON: Yes, I think so.

SOCRATES: On the contrary, again, if there are neither teachers nor learners, we might fairly assume the thing cannot be taught?

MENON: That is true; but don't you think there are teachers of virtue? SOCRATES. I have in truth often tried to find if there were teachers off it, but, do what I will, I can find none. Yet there are many on the same search, and especially those whom I believe to be best skilled in the matter. (Enter ANYTOS) Why look here, my dear Menon, in the nick of time here is Anytos, he has taken a seat beside us. Let us ask him to share in our search; it would be reasonable to give him a share. For in the first place, Anytos has a wealthy father, the wise Anthemion, who became rich not by a stroke of luck or by a gift, like Ismenias the Theban who got "the fortune of a Polycrates" the other day, but he got his by his own wisdom and care. In the next place, his father has a good name generally in the city; he is by no means overbearing and pompous and disagreeable, but a decent and mannerly man; and then he brought up our Anytos well, and educated him well, as the public opinion is — at least, they choose him for the highest offices. It is right to ask the help of such men when we are looking for teachers of virtue, if there are any or not, and who they are. Now then, Anytos, please help us, help me and your family friend Menon here, to find out who should be teachers of this subject. Consider it thus: If we wished Menon here to be a good physician, to whom should we send him to be his teachers? To the physicians, I suppose?

ANYTOS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: And what if we wanted him to be a good shoe-maker, we should send him to the shoemakers?

ANYTOS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And so with everything else?

ANYTOS: Certainly..

SOCRATES: Something else, again, I ask you to tell me about these same things. We should be right in sending him to the physicians, we say, if we wanted him to be a physician. When we say this, do we mean that we should be sensible, if we sent him to those who profess the art, rather than to those who do not, and who also exact a fee for this very thing and declare themselves teachers, for anyone who wants to come and learn? If we looked to such things and sent him accordingly, should we not be doing right?

ANYTOS: Yes.

SOCRATES: Then the same about pipe-playing and the rest. If we want to make anyone a piper, it is great folly to be unwilling to send him to men who undertake to teach the art, and exact a fee for it; and instead to make trouble for others by letting him seek to learn from people who neither pretend to be teachers nor have a single pupil in the art which we want the person we send to learn from them. Don't you think that is plain unreason?

ANYTOS: Yes, by Zeus. I do, even stupidity.

SOCRATES: You are right. Now you can join me in consulting together about our friend Menon here. The fact is, Anytos, he has been telling me this long time that he desires the wisdom and virtue by which men manage houses and cities well. and honour their parents, and know how to entertain fellow-citizens and strangers and to speed them on their way, as a good man ought to do. Then consider whom we should properly send him to for this virtue. Is it not clear from what has just been said that we should send him to those who profess to be teachers of virtue, and declare themselves to he public teachers for any of the Hellenes who wish to learn, with a proper fee fixed to be paid for this?

ANYTOS: And who are these, my dear Socrates?

SOCRATES: You too know, I suppose, that these are the men who are called Sophists.

ANYTOS: O Heracles! Hush, my dear Socrates! May none of my relations or friends, here or abroad, fall into such madness as to go to these persons and be tainted! These men are the manifest canker and destruction of those they have to do with.

SOCRATES: What's that, Anytos? These are the only men professing to know how to do us good, yet they differ so much from the rest that they not only do not help us as the others do, when one puts oneself into their hands, but on the contrary corrupt us? And for this they actually ask pay, and make no secret of it? I, for one, cannot believe you. For I know one man, Protagoras, who has earned more money from this wisdom than Pheidias did for all those magnificent works of his, or any ten other statue-makers. This is a miracle! Those who cobble old shoes or patch up old clothes could not hide it for thirty days if they gave back shoes and clothes worse than they got them, for if they did that they would soon starve to death: but Protagoras, it seems, hid it from all Hellas, and corrupted those who had to do with him, and sent them away worse than he got them, for more than forty years! — for I think he was nearly seventy when he died, after forty years in his art — and in all that time to this day his great name has lasted! And not only Protagoras, but very many others, some born before his time and others living still. Are we to suppose, according to what you say, that they knew they were deceiving and tainting the young, or did they deceive themselves? And shall we claim that these were madmen, when some call them wisest of all mankind?

ANYTOS: Anything but madmen, Socrates; the young men are much madder who pay them money; and madder still those, their relations, who entrust young people to them; maddest of all, the cities which allow them to come in and do not kick them out — whether he is a foreigner or native who attempts to do such a thing.

SOCRATES: Why, Anytos, have you ever been wronged at all by Sophists? What makes you so hard on them?

ANYTOS: Good God, I have never had anything to do with one, and Y would never allow anyone else of my family to have to do with them.

SOCRATES: Then you are quite without experience of these men?

ANYTOS: And I hope I may remain so.

SOCRATES: Astonishing! Then how could you know anything about this matter, whether there is anything good or bad in it, if you are quite without experience of it?

ANYTOS: Easily. At least I know who these are; whether I have experience of them or not.

SOCRATES: Perhaps you are a prophet, Anytos; since how indeed otherwise you could know about them, from what you say yourself, I should wonder. But we were not trying to find out who those are that Menon might go to and become a scoundrel — let them be Sophists if you like — but those others, please tell us and do good to this, your family friend, by showing him some to whom he should go in all this great city, who could make him of some account in that virtue which I described just now.

ANYTOS: Why didn't you show him?

SOCRATES: Well, I did say whom I thought to be teachers of these things, but it turns out I made a mess of it, so you say; and perhaps there is something in what you maintain. Now pray take your turn, and tell him which of the Athenians he should try. Tell us a name, of anyone you like.

ANYTOS: Why ask for the name of one man? Any well-bred gentleman of Athens he might meet will make him better than Sophists can, every single one of them, if he will do as he is told.

SOCRATES: Did these well-bred gentlemen become like that by luck? Did they learn from no one, and can they nevertheless teach other people what they themselves never learnt?

ANYTOS: I suppose they learnt from their fathers, who were also gentlemen before them; or do not you think there have been plenty of fine men in our city?

SOCRATES: I think, Anytos, that there are plenty of men here good at politics, and that there have been plenty before no less than now; but have they been also good teachers of their virtue? For this is what our discussion is really about — not if there are or have been good men here, but if virtue can be taught — that is what we have been considering for so long. And the point we are considering is just this: whether the good men of these times and of former times knew how to hand on to another that virtue in which they were good, or whether it cannot be handed on from one man to another, or received by one man from another — that is what we have been all this while trying to find out, I and Menon. Well then, consider it thus, in your own way of discussing: Would you not say Themistocles was a good man?

ANYTOS: Indeed I should, none better.

SOCRATES: And also a good teacher of his own virtue, if ever anyone was?

ANYTOS: That is what I think, of course if he wished.

SOCRATES: But don't you think he would have wished others to be fine gentlemen, especially, I take it, his own son? Or do you think he grudged it to him, and on purpose did not pass on the virtue in which he was good? I suppose you have heard that Themistocles had his son Cleophantos taught to be a good horseman. At least, he could remain standing upright on horseback, and cast a javelin upright on horseback, and do many other wonderful feats which the great man had him taught, and he made him clever in all that could be got from good teachers. Haven't you heard this from older men?

ANYTOS: Oh yes, I have heard that,

SOCRATES: Then no one could have blamed his for lack of good natural gifts.

ANYTOS: Perhaps not.

SOCRATES: What do you say to this, then that Cleophantos became a good and wise man in the same things as his father Themistocles, did you ever hear that from young or old?

ANYTOS: No, indeed.

SOCRATES: Are we to believe, then, that he wished to educate his son in these things, but not to make the boy better than his neighbours in that wisdom in which he was himself wise are we to believe this, if virtue can really be taught?

ANYTOS: Well, upon my word, perhaps not.

SOCRATES: There you have a grand teacher of virtue, whom you admit yourself to be one of the best men of the past! Let us consider another, Aristeides, Lysimachos' son. Do not you admit that he was a good man?

ANYTOS: I do, most assuredly.

SOCRATES: Then this one educated his own son Lysimachos, as far as teachers went, in the best that the Athenians could provide; but did he make him better than anyone else — what do you think? I take it you have met him yourself and you see what he is. Or Pericles, if you like, a man magnificently wise — you know he brought up two sons, Paralos and Xanthippos?

ANYTOS: Oh yes.

SOCRATES: Well, he taught them (you know that, as I do) to be horsemen as good as any in Athens; he educated them in the fine arts and gymnastics and all the rest, to be as good as any as far as education goes; yet he did not wish to make them good men? oh yes, he wished, as I think, but I take it the thing can't be taught. You must not suppose only a few of our people, or the meanest of them, could not do it: remember Thucydides again — he brought up two sons, Melesias and Stephanos, and gave them a proper education; in particular they were the best wrestlers in Athens — Xanthias was trainer for one, Eudoros for the other — and these had the name of being the best wrestlers. Don't you remember?

ANYTOS: Oh yes, I have heard of them.

SOCRATES: Is it not clear then, that, if virtuous things could be taught, this father would never have had his own children taught these other things, for which fees had to be paid for teaching, and moreover he would never have failed to teach them these virtuous things, by which he could make them good men, without needing to spend anything? But perhaps Thucydides was a mean creature, perhaps he had not crowds of friends in Athens and among our allies!' And he came of a great house, he had great power in the city and all through the nation of Hellenes: so if this could be taught, he would have found the man who could make his sons good, some foreigner or native, in case he himself had no leisure because of his care of the state. The truth is, my dear friend Anytos, I fear virtue cannot be taught.

ANYTOS: My dear Socrates, you seem to speak ill of men easily. I would advise you to be careful, if you will listen to me. Perhaps it is easier to do people harm than good in other cities, but it is very easy in this. I think you yourself knew that perfectly well. (Exit ANYTOS.)

SOCRATES: Menon, I am afraid Anytos is angry, and I don't wonder, for he thinks firstly that I am defaming these men, and secondly he believes he is one of them, himself. But if he ever learns what it is to speak ill, he will no longer be angry; he does not know now. Answer me, please, are there not well-bred, fine gentlemen in your part of the country also?

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: Well then, are they ready to offer themselves to young men as teachers? Do they agree that they are teachers themselves and virtue can be taught?

MENON: No, upon my word, Socrates! but sometimes you might hear them say that it can be taught, sometimes that it cannot.

SOCRATES: Are we to say, then, that they are teachers of virtue, when not even this point is agreed on by them?

MENON: I don't think so, Socrates.

SOCRATES: What next, then: these Sophists of yours who alone make the claim — do you think they are teachers of virtue?

MENON: Gorgias in particular always makes me surprised, Socrates, because you will never hear such a promise from him; indeed he laughs at the others when he hears them promising; making men clever at speaking is what he thinks their job is.

SOCRATES: Then do you not think the Sophists are such teachers either?

MENON: I really can't say, Socrates. I have felt about it much the same as most people; sometimes I think they are, sometimes I don't. . . .

SOCRATES: But if neither the Sophists, nor those who are themselves well-bred, fine gentlemen, are teachers of the subject, it is clear that there are no others?

MENON: Quite clear, I think.

SOCRATES: And if there are no teachers, there are no learners?

MENON: I think so too.

SOCRATES: But we have agreed that if there are neither teachers nor learners of any given thing, this cannot be taught.

MENON: We have.

SOCRATES: No teachers of virtue appear, then?

MENON: NO.

SOCRATES: And if no teachers, no learners?

MENON: So it seems.

SOCRATES: Then virtue could not be taught?

MENON: It looks like it, if our enquiry has been right. So I am wondering now, Socrates, whether there are no good men at all, or what could be the way in which the good men who exist come into being.

SOCRATES: We are really a paltry pair, you and I, Menon; Gorgias has not educated you enough, nor Prodicos me. Then the best thing is to turn our minds on ourselves, and try to find out someone to make us better by hook or by crook. In saying this I have my eye on our recent enquiry, where we were fools enough to miss something; it is not only when knowledge guides mankind that things are done rightly and well; and perhaps that is why we failed to understand in what way the good men come into being.

MENON: What do you mean by that, Socrates?

SOCRATES: This: That the good men must be useful; we admitted, and rightly, that this could not be otherwise.

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: Yes, and that they will be useful if they guide our business rightly, we admitted also: was that correct?

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: But that it is not possible to guide rightly unless one knows, to have admitted that looks like a blunder.

MENON: What do you mean?

SOCRATES: I will tell you. If someone knows the way to Larissa, or where you will, and goes there and guides others, will he not guide rightly and well?

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: Well, what of one who has never been there, and does not know the way; but if he has a right opinion as to the way, won't he also guide rightly?

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: And so long as he has a right opinion about that of which the other has knowledge, he will be quite as good a guide as the one who knows, although he does not know, but only thinks, what is true.

MENON: Quite as good.

SOCRATES: Then true opinion is no worse guide than wis dom, for rightness of action; and this is what we failed to see just now while we were enquiring what sort of a thing virtue is. We said then that wisdom alone guides to right action; but, really, true opinion does the same.

MENON: So it seems.

SOCRATES: Then right opinion is no less useful than knowledge.

MENON: Yes, it is less useful; for he who has knowledge would always be right, he who has right opinion, only sometimes.

SOCRATES: What! Would not he that has right opinion always be right so long as he had right opinion?

MENON: Oh yes, necessarily, I think. This being so, I am surprised, Socrates, why knowledge is ever more valued than right opinion, and why they are two different things.

SOCRATES: Do you know why you wonder, or shall I tell you?

MENON: Oh, tell me, please.

SOCRATES: Because you have not observed the statues of Daidalos. But perhaps you have none in your part of the world.

MENON: What are you driving at?

SOCRATES: They must be fastened up, if you want to keep them; or else they are off and away.

MENON: What of that?

SOCRATES: If left loose there is not much value in owning one of his works — like a runaway slave; it doesn't stay; but chained up it is worth a great deal; for they are fine works of art. What am I driving at? Why, at the true opinions. For the true opinions, as long as they stay, are splendid and do all the good in the world; but they will not stay long-off and away they run out of the soul of mankind, so they are not worth much until you fasten them up with the reasoning of cause and effect. But this, my dear Menon, is remembering, as we agreed before. When they are fastened up, first they become knowledge, secondly they remain; and that is why knowledge is valued more than right opinion, and differs from right opinion by this bond.

MENON: I do declare, Socrates, you have a good comparison there.

SOCRATES: Well, I speak by conjecture, not as one who knows; but to say that right opinion is different from knowledge, that, I believe, is no conjecture in me at all. That I would say I know; there are few things I would say that of, but this I would certainly put down as one of those I know.

MENON: You are quite right in saying this, Socrates.

SOCRATES: Now then, is this not right: True opinion guiding achieves the work of each action no less than knowledge?

MENON: Yes, I think that also is true.

SOCRATES: Then right opinion is nothing inferior to knowledge, and will be no less useful for actions; and the man who has right opinion is not inferior to the man who has knowledge.

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: Again, the good man we have agreed to be useful.

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: Since, then, not only by knowledge would men be good and useful to their cities (if they were so) but also by right opinion, and since neither knowledge nor true opinion comes to mankind by nature, being acquired — or do you think that either of them does come by nature, perhaps?

MENON: NO, not I.

SOCRATES: Therefore they come not by nature, neither could the good be so by nature.

MENON: Not at all.

SOCRATES: Since not by nature, we enquired next whether it could be taught.

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: Well, it seemed that it could be taught if virtue was wisdom.

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: And if it could be taught, it would be wisdom.

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: And if there were teachers, it could be taught, if no teachers, it could not?

MENON: Just SO.

SOCRATES: Further, we agreed that there were no teachers of it?

MENON: That is true.

SOCRATES: We agreed, then, that it could not be taught, and that it was not wisdom? 'The text of Plato is uncertain here.

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: But, however, we agree that it is good?

MENON: Yes.

SOCRATES: And that which guides rightly is useful and good?

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: Again, only these two things guide rightly, right opinion and knowledge; and if a man has these, he guides rightly — for things which happen rightly from some chance do not come about by human guidance: but in all things in which a man is a guide towards what is right, these two do it, true opinion and knowledge.

MENON: I think so.

SOCRATES: Well, since it cannot be taught, no longer is virtue knowledge.

MENON: It seems not.

SOCRATES: Then of two good and useful things one has been thrown away, and knowledge would not be guide in political action.

MENON: I think not.

SOCRATES: Then it was not by wisdom, or because they are wise, that such men guided the cities, men such as Themistocles and those whom Anytos told us of; for which reason, you see, they could not make others like themselves, because not knowledge made them what they were.

MENON: It seems likely to be as you say, Socrates.

SOCRATES: Then if it were not knowledge, right opinion is left, you see. This is what politicians use when they keep a state upright; they have no more to do with understanding than oracle-chanters and diviners, for these in ecstasy tell the truth often enough, but they know nothing of what they say.

MENON: That is how things really are.

SOCRATES: Then it is fair, Menon, to call those men divine, who are often right in what they say and do, even in grand matters, but have no sense while they do it.

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: Then we should be right in calling these we just mentioned divine, oracle-chanters and prophets and the poets or creative artists, all of them; most of all, the politicians, we should say they are divine and ecstatic, being inspired and possessed by the god when they are often right while they say grand things although they know nothing of what they say.

MENON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: And the women, too, Menon, call good men divine; and the Laconians when they praise a good man say, "A divine man that!"

MENON: Yes, and they appear to be quite right, my dear Socrates, although our friend Anytos may perhaps be angry with you for saying it.

SOCRATES: I don't care. We will have a talk with him by and by, Menon. But if we have ordered all our enquiry well and argued well, virtue is seen as coming neither by nature nor by teaching; but by divine allotment incomprehensively to those to whom it comes — unless there were some politician so outstanding as to be able to make another man a politician. And if there were one, he might almost be said to be among the living such as Homer says of Teiresias among the dead, for Homer says of him that he alone of those in Hades has his mind, the others are flittering shades. In the same way also here on earth such a man would be, in respect of virtue, as something real amongst shadows.

MENON: Excellently said, I think, Socrates.

SOCRATES: Then from this our reasoning, Menon, virtue is shown as coming to us, whenever it comes, by divine dispensation; but we shall only know the truth about this clearly when, before enquiring in what way virtue comes to mankind, we first try to search out what virtue is in itself.

But now it is time for me to go; and your part is to persuade your friend Anytos to believe just what you believe about it, that he may be more gentle; for if you can persuade him, you will do a service to the people of Athens also.