NATURALLY, in forming judgments, we depend first of all upon our observation, or more strictly speaking, upon the perceptions of our senses — hearing, touch, smell, taste, as well as sight; the accumulation and repetition of these sense perceptions and of our interpretation of them becomes what we may call experience; and the power that stores them up in our mind we term memory.

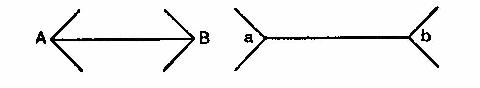

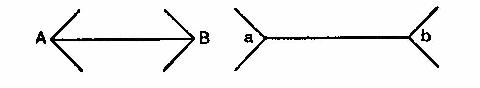

The old adage says "Seeing is Believing," but it is a notorious fact that our eyes can easily lead us astray. The reader is probably familiar with the optical illusion illustrated below:

AB and ab are identical in length, and yet AB looks shorter than ab. Again, if you plunge your right hand into a bowl of hot water and your left into a bowl of cold water, and then both into a bowl of tepid water, the right hand will feel cold and the left will feel hot.

How often, too, is it found that reliable eyewitnesses may give substantially different accounts of the same simple occurrence! Why is this?

It is possible to see things, without noticing or being aware of them. The eye registers an impression of everything that comes within the range of its view; but our awareness depends upon a number of circumstances; our attention may be weak, or intermittent, or distracted; we may be preoccupied; we may be in poor bodily health. Again, the direction of our attention is naturally determined by our interests at the time or by our point of view. We may see things, even notice them, and then dismiss them as being of no consequence or significance. "There are none so blind as those that won't see " — this old proverb tells us that we can even shut our eyes and refuse to see what runs counter to our desires.

Indispensable parts of a successful conjurer's stock-in-trade are the superfluous gestures and interminable patter which he hopes will distract the attention of his audience from the significant movements necessary to perform his tricks.

Professor Dover Wilson in one of his latest contributions to Shakespearean research — What Happens in Hamlet — suggests a very ingenious solution to a problem in that puzzling play which up to now has received no adequate explanation. How is it that Claudius remains unmoved while witnessing the dumb-show which clearly epitomises the play to follow, and yet is not strong enough to sit through the play itself? The answer, says Professor Wilson, is simple enough — Claudius never saw the dumbshow, for his attention had been distracted.

Mr G. K. Chesterton in The Invisible Man, one of his "Father Brown" stories, gives a good illustration of the common failure on the part of observers to see anything they are not expecting to see. A manservant, a commissionaire, a policeman and a street vendor are persuaded to watch the entrance to a block of flats and to notice whether any man, woman or child went in. When their reports are collected, they all swear with varying degrees of emphasis that nobody had entered or left. But, as Father Brown points out later, " when those four quite honest men said that no man had gone into the Mansions, they did not really mean that no man had gone into them. They meant no man whom they could suspect. A man did go into the house, and did come out of it, but they never noticed him." It was the postman!

The danger to which many of us are too often prone is that of interpreting what we see in the light of preconceived opinion. A shop assistant giving evidence regarding a hold-up asserted that her assailant threatened her with a revolver. It turned out to be a tobacco-pipe! About the time when there was a great revival in England of interest in the rearing of pedigree cattle, Maria Edgeworth wrote a book entitled Irish Bulls. It found a ready sale amongst farmers!

I was present some years ago at a lecture by a professor of psychology. He began by talking to us about Napoleon's campaigns and referred to the battles of Marengo, Hohenlinden, Austerlitz, Jena, etc. Suddenly, without warning, he produced and showed for a second a piece of white cardboard with a word on it printed in large capitals. He asked us to write down the word we had seen. The majority of us wrote BATTLE. As a matter of fact the word was BOTTLE! Authors frequently find difficulty in detecting printers' errors in the proofs of their own writings. Familiarity with the words they have originally written makes them read rapidly and carelessly; they see perhaps one or two letters in a word, or one or two words in a sentence correctly printed, but the rest of the word or sentence escapes their eye and is taken for granted. Errors they miss in this way are more easily detected by proof-readers who approach the text without any previous knowledge of its contents.

Another source of deception is the habit we have of confusing details of what we have seen with the inferences made from them. As soon as the mind receives sense impressions it proceeds to interpret them in the light of experience; the interpretation or inference follows so quickly that in actual practice it is bound up so closely with the sense impression that it is difficult to separate the two. A very great part of our so-called facts of observation consists of partial sense impressions completed by rapid interpretations or inferences supplied from imagination, memory, or previous experience. We hear droning noises of various degrees of intensity and we say "bumble-bee," or "hornet," or "aeroplane" without troubling to look in order to discover whether our inference is correct or not. The stage and, to a much larger degree, the 'movies' and 'talkies' rely upon our ability thus to reconstruct the whole from the part.

The more ignorant and uneducated a person is,

"the more difficult it is for him to discriminate between his inferences and the perceptions on which they were grounded. Many a marvellous tale, many a scandalous anecdote owes its origin to this incapacity. The narrator relates, not what he saw or heard, but the impressions which he derived from what he saw or heard, and of which perhaps the greater part consisted of inference, though the whole is related not as inference, but as matter of fact."

The person who says, "I see there's someone ill at Number So-and-so," when the sole evidence is a doctor's car standing outside, sees no such thing: what he really sees is an appearance equally reconcilable with the inference he made and with other totally different inferences.

One of the most celebrated examples of a universal error produced by mistaking an inference for the direct evidence of the senses was the resistance made, on the ground of common sense, to the Copernican system. People protested that Copernicus's theory contravened the common-sense conclusion, i.e., the conclusion derived from visual observation, that the earth was stationary and that the sun and stars moved round it. They 'saw' the sun rise and set and the stars revolve in circles round the pole. But we now know that they saw no such thing; what they did see was a number of natural phenomena which could be equally well explained by a totally different theory.

Again, when the sense impression has been received and interpreted, the mental process is still incomplete; it is nearly always accompanied by some emotional reaction, i.e., our feelings — pleasure, disgust, shame, etc. — are stirred at the same time. These too often affect our inferences and distort our interpretation of what we have seen. For example, in witnessing a street accident in which a pedestrian and a motor car are involved, our observation and our inferences may be affected by pity for the victim, or by sympathy with the driver of the car.

The influence of emotion upon our inferences often takes the form of "making the wish father to the thought" i.e., we imagine that we have seen evidences of what we wished to see. This probably accounts for the 'evidences' supporting the stories of that fabulous Russian army which the majority of the British people believed had landed in Scotland in the August of and had been transported by rail to a southern port and thence conveyed by ship to France. In those anxious and gloomy early days of the first Great War, people were ready to believe any heartening report, and those 'eyewitnesses' who were addressed by strange-looking soldiers (i.e., 'Cossacks') in a barbaric tongue from railway-carriage windows or who saw foreign (i.e., 'Russian') coins taken from station-platform automatic machines were too excited to draw rational inferences from what they did actually see or hear. If, indeed, they were not romancing altogether. Similar emotional excitement on the part of those who accepted these 'evidences' as based on fact was responsible for making them form mistaken estimates of what was probable or even possible in the circumstances. (Compare later.)

Such are the main sources of error in observation; and it should be remembered that everything said about seeing applies equally to bearing and all the other senses.

Lastly, memory — the power that enables us to store up experience — is not always a safe guide. Most people tend to remember incidents attended with feelings of pleasure and warmth, and to repress the memory of those unpleasant incidents which sends a shiver down the spine. Distance often lends enchantment to the view. The passage of time frequently casts a halo about past events. Memory has a habit of exaggerating or minimising pleasant or unpleasant sensations. Memory, too, may play strange pranks. Charles Lamb once quoted a passage he "remembered" from Dante, and Hazlitt, wishing to quote it also, asked Lamb for the exact reference. Lamb couldn't find it and said he must have written it himself! A friend of mine was once discussing the Irish Question with an old woman. She said that the Bible was on her side and quoted:

"The land belongeth to the tenant and not to the landlord, saith the Lord."

In this way faulty or fictitious memory can create 'authority.' That brilliant essay on the nature of memory — 1066 and All That — contains many relevant examples of the unsatisfactory way in which the mind often works. "Sir Walter Raleigh was executed for being left over from the last reign" is a good specimen of the type of impossible half-belief which lingers at the back of the mind after imperfect digestion of highly condensed historical text-books.

Again, the tendency is for us to remember only those facts or instances which bear out a belief we already possess; we shrink from the special effort required to take account of negative evidence. How easy, for example, it was to forget some of the circumstances connected with British colonial expansion, when we held up our hands in pious horror at Italy's treatment of Abyssinia! Superstitious people will be ready to quote examples of fatalities occurring, say, after thirteen have sat down to table; they have forgotten, or have not troubled to remark, how often similar fatalities have followed the sitting down of twelve or fourteen; or the cases where thirteen have sat down to table and no fatality at all has ensued.

This disposition to neglect negative evidence is one of the forms that the working of prejudice may take, and was noted in Chapter Four. In Bacon's Novum Organum there is a passage on the subject which I have taken the liberty of paraphrasing and modernising thus:

When any belief is popularly held, perhaps because it brings comfort or pleasure to its holders, every fresh circumstance is made to support and confirm it; and, although many strong evidences may seem to contradict it, people either shut their eyes to them or depreciate them or get rid of them in some other way, rather than sacrifice their cherished conviction. A man was once shown in a temple the votive tablets hung on the walls by people who had escaped the perils of shipwreck and was asked whether he was not then convinced that his scepticism regarding the power of the gods was ill-founded. His answer — and a very good one, too — was:

"But where are the portraits of those who perished in spite of their vows?"

All superstitions are much the same — astrology, dreams, omens and the like — in which the deluded observers note and remember the prophecies which are fulfilled but neglect or forget those which come to nothing, even though the latter may be much more common. Apart from the fact that people, especially ignorant people, do not relish having their cherished convictions upset, they are peculiarly prone to the error of paying more attention and giving greater weight to affirmatives than to negatives; whereas in trying to establish the truth of any proposition, they should give far more consideration to those instances that appear to point to the contrary

If at the time of observation, or a short time subsequently, we are unable to distinguish what we have seen from the inferences made or the emotions aroused, how much more difficult it will be after some considerable interval has elapsed, during which perhaps we have lived through the experience again in our imagination, and made further inferences with further emotional reactions! Unless we have taken care to make a careful record of our observations when they were still fresh, our memory may, quite unconsciously, distort or elaborate them. A witness's testimony in the law-courts is often a jumble of facts, assumptions and feelings, and a cross-examining counsel is usually not slow to take advantage of his inability to keep them separate, and thus to discredit him as a witness.

In general, the tendency is for people to see what they want to see and to remember what they want to remember. Prejudice thus plays a large part in determining people's power of recall, and the scope and direction of their observation.