People can be divided into two groups according to the way they deal with the excess food when they eat more than they require for their daily expenditure of energy.

In 1950 at the Royal Society of Medicine in London, Professor Sir Charles Dodds, who is in charge of the Courtauld Institute of Biochemistry at the Middlesex Hospital, described an experiment he had carried out.

He took people whose weights had been constant for many years and persuaded them to eat double or treble their normal amount of food. They did not put on weight.

He showed that this was not due to a failure to digest or assimilate the extra food and suggested that they responded to over-eating by increasing their metabolic rate (rate of food using) and thus burned up the extra calories.

He then over-fed people whose weights had not remained constant in the past and found that they showed no increase in metabolism but became fat.

So two people of the same size, doing the same work and eating the same food will react quite differently when they overeat. One will stay the same weight and the other will gain.

We all know that this is true even without scientific proof and yet the fact has not been taken into account or explained by any of the experts who write popular books and articles about slimming.

They write as though fat people and thin people deal with food in the same way. Here is the medical correspondent of The Times (11th March, 1957) On the subject:

"It is no use saying as so many women do 'But I eat practically nothing.' The only answer to this is: No matter how little you imagine you eat, if you wish to lose weight you must eat less. Your reserves of fat are then called on to provide the necessary energy — and you lose weight."

The doctor who wrote these rather heartless words may fairly he taken as representative of medical opinion to-day. He is applying the teachings of William Wadd, Surgeon Extraordinary to the Prince Regent, who in 1829 attributed obesity to "an over-indulgence at the table" and gave, as the first principle of treatment, "taking food that has little nutrition in it."

Fat people can certainly lose weight by this method but what do they feel like while they are doing it? Terrible!

Ask any fat person who has tried it. Many of these unfortunate people really do eat less than people of normal proportions and still they put on weight, and when they go on a strict low-calorie diet which does get weight off, they feel tired and irritable because they are subjecting themselves to starvation. Worse still, when they have reduced and feel they can eat a little more, up shoots their weight again in no time, on quite a moderate food intake.

It is all most discouraging. "Surely there must be some better way of going about it," they say. This book explains that there is. To-day a lot more is known about how fat people get fat and why. Many of the facts have been known for years, but because they have not fitted in with current theories on obesity, they have been ignored.

In the last ten years, however, atomic research has given the physiologist enormous help in unravelling the biochemical reactions which go on in the body.

Radio-active isotopes have been used to "tag" chemical substances so that their progress through the body could be followed, in the same way as birds are tagged in order to establish the paths of their migration.

By this means, details of the metabolism of fats and carbohydrates, previously shrouded in mystery, have been clarified and with the new information so gained old experimental findings have been given new interpretations and the jigsaw of seemingly contradictory facts about obesity has clicked into a recognisable picture.

The first thing to realise is that it is carbohydrate (starch and sugar) and carbohydrate only which fattens fat people.

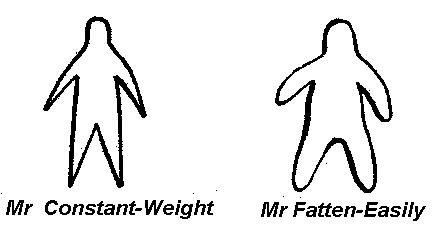

Here is what happens when Mr. Constant-Weight has too much carbohydrate to eat:

Nothing is left over for laying down as fat.

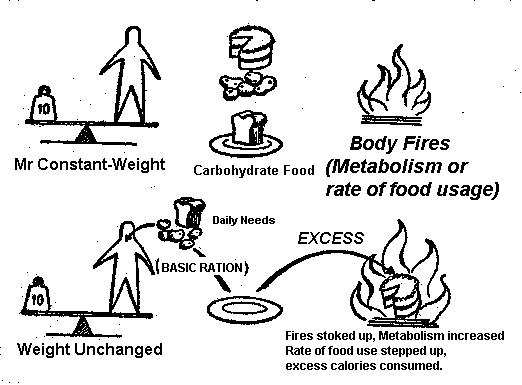

When Mr Fatten-Easily eats too much bread, cake and potatoes, the picture is entirely different:

Why does he fail to burn up the excess? The answer is the real reason for his obesity:

BECAUSE HE HAS A DEFECTIVE CAPACITY FOR DEALING WITH CARBOHYDRATES.

William Banting found this out a hundred years ago and by applying the knowledge, he knocked off nearly 3½ stones in a year, painlessly and without starvation, enjoying good food and good wine while he did it.

He learnt from his doctor that carbohydrate is the fat man's poison. Here is what he wrote:

"For the sake of argument and illustration I will presume that certain articles of ordinary diet, however beneficial in youth, are prejudicial in advanced life, like beans to a horse, whose common ordinary food is hay and corn. It may be useful food occasionally, under peculiar circumstances, but detrimental as a constancy. I will, therefore, adopt the analogy, and call such food human beans. The items from which I was advised to abstain as much as possible were: Bread . . butter...sugar, beer, and potatoes, which had been the main (and, I thought, innocent) elements of my existence, or at all events they had for many years been adopted freely. These, said my excellent adviser, contain starch and saccharine matter, tending to create fat, and should be avoided altogether."

William Banting (1797-1878) was the fashionable London undertaker who made the Duke of Wellington's coffin.

He was a prosperous, intelligent man, but terribly fat. In August, 1862, he was 66 years old and weighed 202lb. He stood only 5 feet 5 inches in his socks. No pictures of him are available to-day, but he must have been nearly spherical.

He was so over-weight that he had to walk downstairs backwards to avoid jarring his knees and he was quite unable to do up his own shoe-laces. His obesity made him acutely miserable.

For many years he passed from one doctor to another in a vain attempt to get his weight off. Many of the doctors he saw were both eminent and sincere. They took his money but they failed to make him thinner.

He tried every kind of remedy for obesity: Turkish baths, violent exercise, spa treatment, drastic dieting; purgation; all to no purpose. Not only did he not lose weight, many of the treatments made him gain.

At length, because he thought he was going deaf, he went to an ear, nose and throat surgeon called William Harvey (no relation to the Harvey who discovered the circulation of the blood). This remarkable man saw at once that Banting's real trouble was obesity, not deafness, and put him on an entirely new kind of diet.

By Christmas, 1862, he was down to 184 lb. By the following August he weighed a mere 156 lb. — nearly right for his height and age.

In less than a year he had lost nearly 50 lb. and 12¼ inches off his waist-line. He could put his old suits on over the new ones he had to order from his tailor!

Naturally, Banting was delighted. He would gladly have gone through purgatory to reach his normal weight but, in fact, Mr. Harvey's diet was so liberal and pleasant that Banting fed as well while he was reducing as he had ever done before.

What was the diet which performed this miraculous reduction? We have Banting's own word for it, in his little book Letter on Corpulence addressed to the public, published in 1864.

Here is what he ate and drank:

| William Banting's Diet (1864) (Losing 46lb ) | |

|---|---|

| Breakfast | Four or five ounces of beef, mutton, kidneys, broiled fish, bacon or cold meat of any kind except pork. One small biscuit or one ounce of dry toast. A large cup of tea without milk or Sugar. |

| Lunch | Five or six ounces of any fish except salmon, any meat except pork, any vegetable except potato. Any kind of poultry or game. One ounce of dry toast. Fruit. Two or three glasses of good claret, sherry or Madeira. (Champagne, port and beer were forbidden.) |

| Tea | Two or three ounces of fruit. A rusk or two. A cup of tea without milk or sugar. |

| Supper | Three or four ounces of meat or fish as for lunch. A glass of claret, or two. Night-cap (if required): A tumbler of grog (gin, whisky or brandy with water but without sugar) or a glass or two of claret or sherry. |

In terms of calories this diet adds up to the astonishing figure of 2,800. An average modern low-calorie reducing diet allows a meagre 1,000 calories a day.

There must therefore have been something other than calorie reduction responsible for Banting's weight loss. What was the secret?

In his own words:

"I can now confidently say that QUANTITY of diet may be safely left to the natural appetite; and that it is the QUALITY only which is essential to abate and cure corpulence."

The diet was made up almost entirely of protein, fat, alcohol and roughage, with, of course, the vitamins and mineral salts contained in these foods. Mr. Harvey, who designed it, had realised that it is carbohydrate (starch and sugar) which fattens fat people.

This is the simple fact which explains Banting's highly satisfactory weight reduction on a high-calorie low-carbohydrate diet. Perhaps it was too simple, for in spite of the excellent book which he published at his own expense and in which he gave all the credit to his doctor, William Harvey, the medical profession refused to believe it.

Banting's name passed into the language as a synonym for slimming but he himself was ridiculed and denounced as a charlatan. His method was never properly understood and was soon forgotten.

To appreciate just how remarkable it was for Mr. Harvey to have designed this revolutionary and successful treatment for Banting's obesity, it is necessary to know something of the medical opinions current at the time.

In 1850 the medical profession in Europe had accepted the theory of a German chemist, Baron Justus von Liebig (1803-1873), that carbohydrate and fat supplied the carbon which combined with oxygen in the lungs to produce body heat. In terms of this theory, carbohydrate and fat were "respiratory foods" and the cause of obesity was believed to be an over-indulgence in these: or as contemporary phraseology had it:

"For the formation of body fat it is necessary that the materials be digested in greater quantity than is necessary to supply carbon to the respiration...."

The principle of the treatment of obesity based on this theory was to cut off as far as possible the supply of food, especially dietary fat, and to accomplish this the patient was exhorted to establish "an hourly watch over the instinctive desires," .i.e. was subjected to starvation.

William Wadd had already advocated such methods and right down to The Times medical correspondent to-day, doctors have gone on slavishly copying them in spite of the mounting evidence that they were unsatisfactory, at least from the patient's point of view, if not from the physician's.

It is easy to say that there were no fat people in Belsen so long as you do not have to experience Belsen yourself.

With this background of medical indoctrination on the subject of obesity to which many doctors have succumbed since, with far less excuse, William Harvey went to Paris in 1856 and attended the lectures of Claude Bernard (1813-1878), the great French physiologist.

He heard Bernard expound his new theory that the liver made not only bile but also a peculiar substance related to starches and sugars, to which the name glucose had been given.

Relating this new idea to the already well-known ones,

"that a saccharine and farinaceous diet is used to fatten certain farm animals,"

and

"that a purely animal diet greatly assists in checking the secretion of a diabetic urine,"

Harvey did some original and constructive thinking. This is how he put it:

"That excessive obesity might be allied to diabetes as to its cause, although widely diverse in its development; and that if a purely animal diet were useful in the latter disease, a combination of animal food with such vegetable diet as contained neither sugar nor starch, might serve to arrest the undue formation of fat."

Now in Harvey's time, biochemistry was in its infancy and physiology was only just emerging from the shadow of the middle ages, so he could not explain his theory of altered carbohydrate metabolism in exact chemical terms. But he could test it out in practice and it was at this point, in 1862, that William Banting consulted him. We have Banting's own description of the happy results of that meeting.

The subsequent history of William Harvey and his patient is interesting. It shows how social and economic influences and the desire to run with the herd, which is in all of us, can cloud scientific discoveries with compromise and in bringing them into line with orthodoxy can rob them of all practical value.

Banting published his Letter on Corpulence in 1864, privately, because he feared, not without reason as it turned out, that the Editor of the Lancet, to whom he first thought of submitting it, would refuse to publish anything "from an insignificant individual without some special introduction."

The same sort of objection deterred him from sending it to the Cornhill Magazine, which had recently carried an article, "What is the cause of obesity?", which in Banting's view was not altogether satisfactory.

Banting's pamphlet attracted immediate attention and was widely circulated. The treatment he described was phenomenally successful. The "Banting diet" then became the centre of bitter controversy. No one could deny that the treatment was effective but having first appeared in a publication by a layman, the medical profession, which was just beginning to climb the social ladder and was very much on its frock-coated dignity, felt bound to attack it.

The diet was criticised as being freakish and unscientific. Harvey came in for much ridicule and vituperation and his practice as a surgeon began to suffer.

But the obvious practical success of the "non-farinaceous, non-saccharine" (high-fat, high-protein, low carbohydrate) diet called for some explanation from the doctors, and this was supplied by Dr. Felix von Niemeyer of Stuttgart, whose name was associated with a pill containing quinine, digitalis and opium. German physicians were then very fashionable.

Basing his argument on the teachings of Liebig, Niemeyer explained Banting's diet as follows: Protein foods are not converted to body fat, but the "respiratory foods," fat and carbohydrate, are. He interpreted meat as lean meat and described the diet in terms which today would mean that it was a high-protein, low-calorie diet with fat and carbohydrate both restricted.

Of course the diet which actually slimmed Banting was not like that at all. It was a high-fat, high-protein, unrestricted calorie diet with only carbohydrate restricted.

The confusion about what Banting actually ate still exists today. It arises because few people have read his book in the original and fewer still have read Harvey's papers. I have quoted the relevant passages from both sources earlier in this chapter, and from these quotations two things are clear:

1. That Harvey believed starch and sugar to be the culprits in obesity.

2. That within the limits of his imperfect knowledge of the chemical composition of foods, Harvey tried to exclude these items from Banting's diet, allowing him to eat as much as he liked of everything else.

Harvey had allowed Banting to take meat, including venison, poultry and fish—with no mention of trimming off the fat—in quantities up to 24 ounces a day which gives a calorie intake of about 2,800 when the alcohol and other things he ate and drank are included.

By deliberately lumping fat and carbohydrate together where Harvey had tried to separate them, Dr. Niemeyer had effectively turned Banting's diet upside down, and the day was saved for the pundits. Niemeyer's explanation was eagerly accepted and "modified Banting" diets, based upon this phoney explanation, found their way into the text-books for the rest of the nineteenth century.

While all this "rationalisation" of his diet was going on, William Harvey was feeling the cold draught of unpopularity with his colleagues and nine years after the publication of Banting's pamphlet he publicly recanted. He came into line with Dr. Niemeyer and explained apologetically:

"Had Mr. Banting not suffered from deafness the probability is that his pamphlet would not have appeared."

Thus Harvey was able to continue his peaceful career as a respected ear, nose and throat surgeon. But Banting stuck to his guns and in 1875 published letters showing that obese people lost weight effectively and painlessly through eating large quantities of fat meat.

In spite of an almost total lack of scientific knowledge of the chemical composition of different foods, Banting remained true to the principle William Harvey had taught him: avoidance of starchy and sugary foods as he knew them.

He kept his weight down without difficulty and lived in physical comfort to the age of 81.

This distortion of a genuine discovery, based on original observation, to make it fit in with current theories has happened again and again in our history.

Ever since Procrustes cut off the feet of people who did not fit his bed, established authorities with narrow minds have employed the cruel weapons of ridicule and economic sanctions against people who challenged their doctrines.

To the student of psychology this is a commonplace, but it is a great brake on scientific progress. The howl that went up against Harvey and Banting was nearly as loud as the one which greeted Freud's Interpretation of Dreams in which he pointed out the facts of infantile sexuality. This is hardly surprising when one considers how sensitive most of us are to criticism of our views on our pet subjects. Among the many diets which followed the publication of Banting's pamphlet, every variation of the three main foods was tried but always with restriction of the total intake.

It seemed that in spite of the real value of Harvey's observations and Banting's application of them, nutritionists could not bring themselves to abandon the idea that to lose weight one must eat less. This principle derived from the law of conservation of energy (what comes out must go in) on the basis of which it was deduced that the energy intake (consumption of food) must exceed the energy expenditure when obesity is developing.

Of course this is perfectly obvious. A man can't get fat unless he eats more food than he uses up for energy. But it is beside the point.

The real question that needs answering about obesity is:

What is the cause of the fat man's failure to use up as much as he takes in as food? It could be that he is just greedy and eats more than he requires. It could also be that although he only eats a normal amount, some defect in the way his body deals with food deflects some of what he eats to his fat stores and keeps it there instead of letting him use it up for energy.

In other words, Mr. Fatten-Easily may have a defect in his metabolism which Mr. Constant-Weight has not.

Too much attention has been paid to the input side of the energy equation and not enough to possible causes of defective output. Even with a low food intake a man may get fat because his output is small. And this need not be because he is taking insufficient exercise but because something is interfering with the smooth conversion of fuel to energy in his body and encouraging its storage as fat.

It is curious that up to 1900, apart from Harvey and Banting, only one person had ever considered this alternative explanation for obesity. This was an eighteenth-century physician, Dr. Thomas Beddoes. In 1793, Beddoes applied the new theory of "pneumatic chemistry" which had originated with M. Lavoisier's experiments in France and held that during respiration the lungs took in oxygen, combined it with carbon derived from the food and expelled it in the form of carbon dioxide.

Beddoes thought that the oxygen might go deeper into the body than the lungs and that obesity might be caused by its combining insufficiently with body fat. This would lead to fat accumulating instead of being burnt up for energy.

He attempted to remedy this supposed defect of fat metabolism by introducing more oxygen into the system— but with no good result.

His theory was easily disposed of by the redoubtable William Wadd, who remarked:

"Dr. Beddoes remained so inconveniently fat during his life that a lady of Clifton used to denominate him the walking feather bed."

So the views of William Wadd prevailed and, apart from the Banting interlude, starvation has been the basis of the treatment of obesity in this country right up to the present day. Only the words have changed.

"Calorie restriction" has now replaced Wadd's "taking food that has little nutrition in it."

Within the principle of total food restriction, most reducing diets gave a high proportion of protein up to the year 1900. Then the American physiologist, Russell Henry Chittenden, published an indictment of protein, purporting to show that it was the cause of many diseases and from that time obese patients were generally kept short of this most vital food in their already short rations. (Lately, protein has been coming back into favour, and most of the current, popular, "Women's Page" slimming diets follow Niemeyer's modification of Banting. That is to say, they are high-protein and low-calorie, with fat and carbohydrate both restricted.)

There was the start of a break away towards more rational thinking on obesity with von Bergmann and the "lipophilia" school. He, like Beddoes, suggested a diminished oxidation of fat and explored the metabolism of the obese for evidence of abnormality which could account for a special affinity for fat and an excess of storage over use.

The snag again — as with Beddoes — the lack of any effective treatment to fit in with the theory.

Harvey had had an effective treatment with no convincing theory. Beddoes and von Bergmann had good theories but no treatment.

So as the twentieth century ran on into the thirties the view became more and more widely accepted that obesity was caused by an inflow of energy greater than the outflow, caused simply by careless over-eating and gluttony.

Popular books on slimming became mainly concerned with tricks for persuading people to eat less while seeming to allow them to eat more.

In 1930, Newburgh and Johnson summed the matter up thus in the Journal of Clinical Investigation:

"Obesity is never directly caused by abnormal metabolism but is always due to food habits not adjusted to the metabolic requirements "; i.e. over-weight never comes from a defective ability to mobilise fat from the fat stores but always from over-eating.

This appeared to be the last word and doctors and slimming "experts" all over the world settled down to trying to persuade their obese patients to eat less.

With the "obesity comes from over-eating" dogma enshrined in history and hallowed by the blessing of the high priests of modern physiological research, imagine the impact on the medical world of the news in 1944, that cases of obesity were being treated effectively at the New York City Hospital with diets in which more than 24 ounces of fat meat was allowed a day. Patients were encouraged to eat to the limit of their appetites and some who were sceptical of the diet ate very copiously indeed. But they still lost weight.

The man in charge of this treatment was Dr. Blake F. Donaldson.

At that time, Great Britain was still in the grip of severe war-time rationing and minimal amounts of fat and protein foods were obtainable. So this American revival of Bantingism was for the time being of academic interest only over here.

But from that time onwards, unrestricted-calorie high-fat, high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets for obesity were on the map again and in the United States at any rate they gradually gained in popularity. Research workers in Britain were not idle, however. Many of them had been to America, and Donaldson's work and later Dr. Alfred Pennington's caused great interest.

Then in July 1956, in the Lancet, Professor Alan Kekwick and Dr. G. L. S. Pawan published the results of a scientific evaluation of Banting's diet undertaken in their wards at the Middlesex Hospital in London. They proved that Banting was right. Here is their conclusion:

"The composition of the diet can alter the expenditure of calories in obese persons, increasing it when fat and proteins are given and decreasing it when carbohydrates are given."

Today this work is being quoted in medical journals all over the world. Here is a quotation from the February 1957 number of the American journal, Antibiotic Medicine and Clinical Therapy:

"Kekwick and Pawan, from the Middlesex Hospital, London, report some news for the obese. All of the obese subjects studied lost weight immediately after admission to hospital and therefore a period of stabilisation was required before commencing investigation.

If the proportions of fat, carbohydrate and protein were kept constant, the rate of weight loss was then proportional to the calorie intake.

If the calorie intake was kept constant, however, at 1,000 per day, the most rapid weight loss was noted with high fat diets . . . But when the calorie intake was raised to 2,600 daily in these patients, weight loss would still occur provided that this intake was given mainly in the form of fat and protein.

It is concluded that from 30 to 50 per cent of weight loss is derived from the total body water and the remaining 50 to 70 per cent from the body fat."

In other words, doctors now have scientific justification for basing diets for obesity on reduction of carbohydrate rather than on reduction of calories and fat.

Before going on it should be explained that Banting did in fact take some carbohydrate. Kekwick and Pawan and other investigators have shown that up to 60 grammes (just under 2 ounces) of carbohydrate a day are compatible with effective weight reduction on a high-fat, high-protein diet, although in some subjects even this amount will slow down the rate of weight loss. In such cases further restriction of carbohydrate with stricter adherence to the high-fat, high-protein foods results in satisfactory weight loss again.

1. There are two kinds of people: the Fatten-Easilies and the Constant-Weights.

2. If a Constant-Weight eats more carbohydrate than he needs, he automatically pushes up his metabolic rate (turns the bellows on his body fires) until the excess has been consumed.

3. A Fatten-Easily cannot do this because of a defect in his body chemistry. Excess carbohydrate is laid down as fat.

4. It is carbohydrate which makes a fat person fat.

5. Medical research has now proved that Banting was right and that diets for obesity may be based successfully on reduction of carbohydrate rather than on restriction of calories and fat.