TITUS, surnamed Vespasian like his father, had such winning ways, perhaps inborn, perhaps cultivated subsequently, or conferred on him by fortune — that he became an object of universal love and adoration. Oddly enough this happened only after his accession: both as a private citizen and later as his father's colleague, Titus had been not only unpopular but venomously loathed. He was born on 30 December 41 A.D., the memorable year of Gaius Caligula's assassination, in a small, dingy, slum bedroom close to the Seven-storey Tenement. The house, which is still standing, has lately been opened to the public.

2.. He grew up at Court with Claudius's son Britannicus, sharing his teachers and following the same curriculum. The story goes that when one day Claudius's freedman Narcissus called in a physiognomist to examine Britannicus's features and prophesy his future, he was told most emphatically that Britannicus would never succeed his father, whereas Titus (who happened to be present) would achieve that distinction. The two boys were such close friends that when Britannicus drank his fatal dose of poison, Titus, who was reclining at the same table, is said to have emptied the glass in sympathy and to have been dangerously ill for some time. He never forgot his friend-ship for Britannicus, but had two statues of him made: a golden one to be installed in the Palace, and an ivory equestrian one which is still carried in the Circus procession, and which he personally followed around the ring at its dedication.

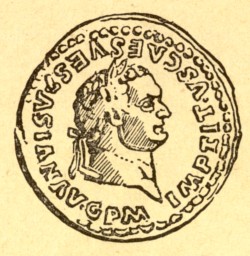

3. When Titus came of age, the beauty and talents that had distinguished him as a child grew even more remarkable. Though not tall, he was both graceful and dignified, both muscular and handsome, except for a certain paunchiness. He had a phenomenal memory, and displayed a natural aptitude alike for the arts of war and peace; handled arms and rode a horse as well as any man living; could compose speeches and verses in Greek or Latin with equal ease, and actually extemporized them on occasion. He was something of a musician, too: sang pleasantly, and had mastered the harp. It often amused him to compete with his secretaries at shorthand dictation, or so I have heard; and he claimed that he could imitate any hand-writing in existence and might, in different circumstances, have been the most celebrated forger of all time.

4. Titus's reputation while an active and efficient colonel in Germany and Britain is attested by the numerous busts and statues of him found in both countries. After completing his military service he returned to Rome where he spent a great deal of time at the law courts as a barrister; but only because he enjoyed pleading cases, not because he meant to make a career of it. The father of his first wife, Arrecina Tertulla, commanded the Guards, the highest post available to a man of equestrian rank. When she died, Titus married the very well-connected Marcia Furnilla, whom he divorced as soon as she had borne him a daughter. When his quaestorship at Rome ended, he went to command one of his father's legions in Judaea, and there captured the fortified cities of Tarichaeae and Gamala. In the course of the fighting he had a horse killed under him, but mounted another belonging to a comrade who fell at his side.

5. Titus was presently sent to congratulate Galba on his accession, and all whom he met on the way were convinced that Vespasian was trying to get him adopted as Galba's heir. Seeing, however, that a new revolution threatened in Rome, Titus turned back to consult the oracle of Venus at Paphos, and there heard his own prospects of wearing the purple mentioned again. The prophecy grew much more credible after his father had been acclaimed Emperor and left him to complete the conquest of Judaea. In the final assault on Jerusalem Titus managed to kill twelve of the garrison with successive arrows; and the city was captured on his daughter's birthday. Titus's prowess inspired such deep admiration in the troops that they hailed him as Emperor and, on several occasions, when he seemed on the point of relinquishing his command, begged him either to stay or to let them follow him; even threatening violence if he would not humour their wishes. Such passionate devotion aroused a suspicion that he planned to usurp his father's power in the East, especially since he had worn a diadem while attending the consecration of the Apis bull at Memphis on his way to Alexandria; but this was a gross slander on his conduct, which accorded with ancient ritual. Titus sailed for Italy at once in a naval transport, touching at Reggio and Puteoli. Hurrying on to Rome, he exploded all the false rumours by greeting Vespasian, who had not been expecting him, with the simple words: 'Here I am, Father, here I am!'

6. He now became his father's colleague, almost his guardian; sharing in the Judaean triumph, in the Censorship, in the exercise of tribunicial power, and in seven consulships. He bore most of the burdens of government and, as his father's secretary, dealt with official correspondence, drafted edicts, and even took over the quaestor's task of reading the Imperial speeches to the Senate. Titus also assumed command of the Guards, a post which had always before been entrusted to a knight, and in which he behaved somewhat high-handedly. If anyone aroused his suspicion, Guards detachments would be sent into theatre or camp to demand the man's punishment in the name of every loyal citizen present; and he would then be executed on the spot. Titus disposed of Aulus Caecina, an ex-Consul, by inviting him to dinner and having him stabbed on the way out; yet here he could plead political necessity — the manuscript of a disloyal speech which Caecina intended for the troops had fallen into his hands. Actions of this sort, although an insurance against the future, made Titus so deeply disliked at the time that perhaps no more unwelcome claimant to the supreme power has ever won it.

7.He was believed to be profligate as well as cruel, because of the riotous parties which he kept going with his more extravagant friends far into the night; and morally unprincipled, too, because he owned a troop of inverts and eunuchs, and nursed a guilty passion for Queen Berenice, to whom he had allegedly promised marriage. He also had a reputation for accepting bribes and not being averse from using influence to settle his father's cases in favour of the highest bidder. It was even prophesied quite openly that he would prove to be a second Nero. However, this pessimistic view stood him in good stead: so soon as everyone realized that here was no monster of vice but an exceptionally noble character, public opinion flew to the opposite extreme.

His dinner parties, far from being orgies, were very pleasant occasions, and the friends he chose were retained in office by his successors as key men in Imperial and national affairs. He sent Queen Berenice away from Rome, which was painful for both of them; and broke off relations with some of his favourite boys — though they danced well enough to make a name for themselves on the stage, he never attended their public performances.

No Emperor could have been less of a robber than Titus, who showed the greatest respect for private property, and would not even accept the gifts sanctioned by Imperial tradition. Nor had any of his predecessors ever displayed such generosity. At the dedication of the Colosseum and the Baths, which had been hastily built beside it, Titus provided a most lavish gladiatorial. show; he also staged a sea-fighton the old artificial lake, and when the water had been let out, used the basin for further gladiatorial contests and a wild-beast hunt, 5,000 beasts of different sorts dying in a single day.

8.Titus was naturally kind-hearted, and though no Emperor, following Tiberius's example, had ever consented to ratify individual concessions granted by his predecessor, unless these suited him personally, Titus did not wait to be asked but signed a general edict confirming all such concessions whatsoever. He also had a rule never to dismiss any petitioner without leaving him some hope that his request would be favourably considered. Even when warned by his staff how impossible it would be to make good such promises, Titus maintained that no one ought to go away disappointed from an audience with the Emperor. One evening at dinner, realizing that he had done nobody any favour since the previous night, he spoke these memorable words: 'My friends, I have wasted a day.'

He took such pains to humour his subjects that, on one occasion, before a gladiatorial show, he promised to forgo his own preferences and let the audience choose what they liked best; and kept his word by refusing no request and encouraging everyone to tell him what each wanted. Yet he openly acknowledged his partisanship of the Thracian school of gladiators, and would gesture and argue vociferously with the crowd on this subject, though never losing either his dignity or his sense of justice. Sometimes he would use the new public baths, as a means of keeping in touch with the people.

Titus's reign was marked by a series of catastrophes — an eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Campania, a fire at Rome which burned for three days and nights, and one of the worst outbreaks of plague that had ever been known. Throughout these frightful disasters, he showed far more than an Emperor's concern: it resembled the deep love of a father for his children, which he conveyed not only in a series of comforting edicts but by helping the victims to the utmost extent of his purse. He set up a board of ex-consuls, chosen by lot, to relieve distress in Campania, and devoted the property of those who had died in the eruption and left no heirs to a fund for rebuilding the stricken cities. His only comment on the fire at Rome was: 'This has ruined me!' He stripped his own houses of their decorations, distributed these among the damaged temples and public buildings, and appointed a body of knights to see that his orders were promptly carried out. Titus attempted to control the plague by every imaginable means, human as well as divine — resorting to all sorts of sacrifices and medical remedies.

One of the worst features of Roman life at the time was the licence long enjoyed by informers and their managers. Whenever Titus laid his hands on any such he had them well whipped, clubbed, and then taken to the Colosseum and paraded in the arena; where some were put up for auction as slaves and the remainder deported to desert islands. In further discouragement of this evil, he allowed nobody to be tried for the same offence under more than one law, and limited the period during which inquiries could be made into the status of dead people.

9. He had promised before his accession to accept the office of Chief Pontiff as a safeguard against committing any crime, and kept his word. Thereafter he was never directly or indirectly responsible for a murder; and, although often given abundant excuse for revenge, swore that he would rather die than take life. Titus dismissed with a caution two patricians convicted of aspiring to the Empire; he told them that since this was a gift of Destiny they would be well advised to renounce their hopes. He also promised them whatever else they wanted, within reason, and hastily sent messengers to reassure the mother of one of the pair, who lived some distance away, that her son was safe. Then he invited them to dine among his friends; and, the next day, to sit close by him during the gladiatorial show, where he asked them to test the blades of the contestants' swords brought to him for inspection. Finally, the story goes, he consulted the horoscopes of both men and warned them what dangers threatened from unexpected quarters — quite correctly, as events proved.

Titus's brother Domitian caused him endless trouble: took part in conspiracies, stirred up disaffection in the armed forces almost openly, and toyed with the notion of escaping from Rome and putting himself at their head. Yet Titus had not the heart to execute Domitian, dismiss him from Court, or even treat him less honourably than before. Instead, he continued to repeat, as on the first day of his reign: 'Remember that you are my partner and chosen successor'; and often took Domitian aside, begging him tearfully to return the affection he offered.

10.Death, however, intervened; which was a far greater loss to the world than to Titus himself. At the close of the Games he wept publicly; and then set off for Sabine territory in a gloomy mood because a victim had escaped when he was about to sacrifice it, and because thunder had sounded from a clear sky. He collapsed with fever at the first posting station, and on his way home in a litter, is said to have drawn back the curtains, gazed up at the sky, and complained bitterly that life was being undeservedly taken from him — since only a single sin lay on his conscience. It was difficult to guess what he meant; and though this enigmatic remark has been taken as referring to incest with Domitian's wife, Domitia, she herself solemnly denied the allegation. Had the charge been true she would surely never have made any such denial but boasted of it — as she did of all her other misdeeds?

11.Titus died at the age of forty-two, in the same country house where Vespasian had also died. It was 1 September, 81 A.D., and he had reigned two years, two months, and twenty days. When the news spread, the common people went into mourning as though they had suffered a personal loss. Senators hurried to the House without waiting for an official summons, and before the doors had been opened, and at once began speaking of him with greater thankfulness and praise than they had ever used while he was among them. Their official eulogies were couched in the same vein.