THE FLAVIANS, admittedly an obscure family, none of whose members had ever enjoyed high office, at last brought stable government to the Empire; they had found it drifting uneasily through a year of revolution in the course of which three successive emperors lost their lives by violence. We have no cause to be ashamed of the Flavian record, though it is generally admitted that Domitian's cruelty and greed justified his assassination.

Titus Flavius Petro, a burgher of Reiti, who fought for Pompey in the Civil War as a centurion, or perhaps a reservist, made his way back there from the battlefield of Pharsalus; secured an honourable discharge, with a full pardon, and took up tax-collecting. Although his son Sabinus is said either to have been a leading centurion, or to have resigned command of a battalion on grounds of ill-health, the truth is that he avoided military service and became a customs supervisor in Asia, where several cities honoured him with statues inscribed: 'To an Honest Tax-gatherer'. He later turned banker in Switzerland, and there died, leaving a wife, Vespasia Polla, and two sons, Sabinus and Vespasian. Sabinus, the elder, attained the rank of City Prefect at Rome; Vespasian became Emperor. Vespasia Polla belonged to a good family from Nursia. Vespasius Pollio, her father, had three times held a colonelcy and been Camp Prefect; her brother entered the Senate as a praetor. Moreover, on a hilltop some six miles along the road to Spoleto, stands the village of Vespasiae, where a great many tombs testify to the family's antiquity and local renown. As for the popular account of their origins — that the Emperor's great-grandfather had been a foreman of the Umbrian labourers who cross the Po every summer to help the Sabines with their harvest, and that he married and settled in Reiti — my own careful researches have turned up no evidence to substantiate this.

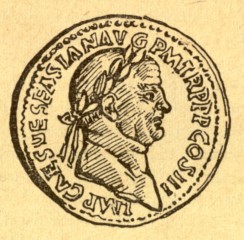

2. Vespasian was born on 17 November 9 A.D., in the hamlet of Falacrina, just beyond Reiti; during the consulship of Quintus Sulpicius Camerinus and Gaius Poppaeus Sabinus, and five years before the death of Augustus. His paternal grandmother, Tertulla, brought him up on her estate at Cosa; and as Emperor he would often revisit the house, which he kept exactly as it had always been, in an attempt to preserve his childhood memories intact. On feast days and holy days, he made a practice of drinking from a little silver cup which had once belonged to his grandmother, so dear was her memory to him.

For years he postponed his candidature for the broad purple stripe of senatorial rank, already earned by his brother, and in the end it was Vespasia Polla who drove him to take this step; not by pleading with him or commanding him as his mother, but by constant sarcastic use of the phrase 'your brother's footman'.

Vespasian served as a colonel in Thrace, and when quaestorships were being assigned by lot, drew that of Crete and Cyrenaica. His first attempt to win an aedileship came to nothing; at the second he scraped through in only the sixth place; however, as soon as he stood for the praetorship, he was one of the most popular choices. The Senate then being at odds with Gaius Caligula, Vespasian, who never missed a chance of winning favour at Court, proposed that special Games should be held to celebrate the Emperor's German victory. He also proposed that, as an additional punishment, the bodies of Lepidus and Gaetulicus, the conspirators, should be denied public burial; and, during a full session of the House, acknowledged the Emperor's graciousness in having invited him to dine at the Palace.

3. Meanwhile, Vespasian had married Flavia Domitilla, the ex-mistress of Statilius Capella, an African knight from Sabrata. Her father, Flavius Liberalis, a humble quaestor's clerk from Ferulium, had appeared before a board of arbitration and established her claim to the full Roman citizenship, in place of only a Latin one. Vespasian had three children by Flavia, namely Titus, Domitian, and Domitilla; but Domitilla died before he held a magistracy, and so did Flavia herself; he then took up with Caenis, his former mistress and one of Antonia's freedwomen secretaries, who remained his wife in all but name even when he became Emperor.

4. On Claudius's accession, Vespasian was indebted to Narcissus for the command of a legion in Germany; and proceeded to Britain, where he fought thirty battles, subjugated two warlike tribes, and captured more than twenty towns, besides the entire Isle of Wight. In these campaigns he served at times under Aulus Plautius, the Consular commander, and at times directly under Claudius, earning triumphal decorations; and soon afterwards held a couple of priest-hoods, as well as a consulship for the last two months of the year. While waiting for a proconsular appointment, however, he lived in retirement: for fear of Agrippina's power over Nero, and of the animosity which she continued to feel towards any friend of Narcissus's even after his death.

In the distribution of provinces Vespasian drew Africa, where his rule was characterized by justice and great dignity, except on a single occasion when the people of Hadrumetum rioted and pelted him with turnips. It is known that he came back no richer than he went, because his credit was so nearly exhausted that, in order to keep up his position, he had to mortgage all his estates to his brother and go into the mule-trade; which gave him the nickname 'Mule Driver'. Vespasian is also said to have earned a severe reprimand after getting a young man raised to senatorial rank, against his father's wishes, for a fee of 2,000 gold pieces.

He toured Greece in Nero's retinue but offended him deeply, by either leaving the room during his song recitals, or staying and falling asleep. In consequence he not only lost the imperial favour but was dismissed from Court, and fled. to a small out-of-the-way town-ship, where he hid in terror of his life until finally offered the military command of a province.

An ancient superstition was current in the East, that out of Judaea would come the rulers of the world. This prediction, as it later proved, referred to two Roman Emperors, Vespasian and his son Titus; but the rebellious Jews, who read it as referring to themselves, murdered their Procurator, routed the Governor-general of Syria when he came down to restore order, and captured an Eagle. To crush this uprising the Romans needed a strong army under an energetic commander, who could be trusted not to abuse his plenary powers. The choice fell on Vespasian. He had given signal proof of energy and nothing, it seemed, need be feared from a man of such modest antecedents. Two legions, with eight cavalry divisions and ten supernumerary battalions, were therefore despatched to join the forces already in Judaea; and Vespasian took his elder son, Titus, to serve on his staff. No sooner had they reached Judaea than he impressed the neighbouring provinces by his prompt tightening up of discipline and his audacious conduct in battle after battle. During the assault on one enemy city he was wounded on the knee by a stone and caught several arrows on his shield.

5. When Nero and Galba were both dead and Vitellius was disputing the purple with Otho, Vespasian began to remember his Imperial ambitions, which had originally been raised by the following omens. An ancient oak-tree, sacred to Mars, growing on the Flavian estate near Rome, put out a shoot for each of the three occasions when his mother was brought to bed; and these clearly had a bearing on the child's future. The first slim shoot withered quickly: and the eldest child, a girl, died within the year. The second shoot was long and healthy, promising good luck; but the third seemed more like a tree than a branch. Sabinus, the father, is said to have been greatly impressed by an inspection of a victim's entrails, and to have congratulated his mother on having a grandson who would become Emperor. She roared with laughter and said: 'Fancy your going soft in the head before your old mother!'

Later, during Vespasian's aedileship, the Emperor Gaius Caligula, furious because Vespasian had not kept the streets clean, as was his duty, ordered some soldiers to load him with mud; they obeyed by stuffing into the fold of his senatorial gown as much as it could hold — an omen interpreted to mean that one day the soil of Italy would be neglected and trampled upon as the result of civil war, but that Vespasian would protect it and, so to speak, take it to his bosom.

Then a stray dog picked up a human hand at the cross-roads, which it brought into the room where Vespasian was breakfasting and dropped under the table; a hand being the emblem of power. On another occasion a plough-ox shook off its yoke, burst into Vespasian's dining room, scattered the servants, and fell at his feet, where it lowered its neck as if suddenly exhausted. He also found a cypress-tree lying uprooted on his grandfather's farm, though there had been no gale to account for the accident; yet by the next day it had taken root again and was greener and stronger than ever.

In Greece, Vespasian dreamed that he and his family would begin to prosper from the moment when Nero lost a tooth; and on the following day, while he was in the Imperial quarters, a dentist entered and showed him one of Nero's teeth which he had just extracted.

In Judaea, Vespasian consulted the God of Carmel and was given a promise that he would never be disappointed in what he planned or desired, however lofty his ambitions. Also, a distinguished Jewish prisoner of Vespasian's, Josephus by name, insisted that he would soon be released by the very man who had now put him in fetters, and who would then be Emperor. Reports of further omens came from. Rome; Nero, it seemed, had been warned in a dream shortly before his death to take the sacred chariot of Jupiter Greatest and Best from the Capitol to the Circus, calling at Vespasian's house as he went. Soon after this, while Galba was on his way to the elections which gave him a second consulship, a statue of Julius Caesar turned of its own accord to face east; and at Betriacum, when the battle was about to begin, two eagles fought in full view of both armies, but a third appeared from the rising sun and drove off the victor.

6. Still Vespasian made no move, although his adherents were impatient to press his claims to the Empire; until he was suddenly stirred to action by the fortuitous support of a distant group of soldiers whom he did not even know: 2,000 men belonging to the three legions in Moesia that were reinforcing Otho. They had marched forward as far as Aquileia, despite the news of Otho's defeat and suicide which reached them on the way, and there taken advantage of a breakdown in local government to plunder at pleasure. Pausing at last to consider what the reckoning might be on their return, they hit on the idea of setting up their own Emperor. And why not? After all, the troops in Spain had appointed Galba; and the Guards, Otho; and the troops in Germany, Vitellius. So they went through the whole list of provincial governors, rejecting each name in turn for this reason or that, until finally choosing Vespasian — on the strong recommendation of some Third Legion men who had been sent to Moesia from Syria just prior to Nero's death — and marking all their standards with his name. Though they were temporarily recalled to duty at this point, and did no more in the matter, the news of their decision leaked out. Tiberius Alexander, the Prefect in Egypt, thereupon made his legions take the oath to Vespasian; this was 1 July, later celebrated as Accession Day, and on 11 July the army in Judaea swore allegiance to Vespasian in person.

Three things helped him greatly. First, the copy of a letter (possibly forged) in which Otho begged him most earnestly to save Rome and take vengeance on Vitellius. Second, a persistent rumour that Vitellius had planned, after his victory, to re-station the legions, transferring those in Germany to the Orient, a much softer option. Lastly, the support of Lucius Mucianus, then commanding in Syria, who, swallowing his jealousy of Vespasian which he had long made no effort to hide, promised to lend him the whole Syrian army; and the support of Vologaesus, King of the Parthians, who promised him 40,000 archers.

7. So Vespasian began a new civil war: having sent troops ahead to Italy, he crossed into Africa and occupied Alexandria, the key to Egypt. There he dismissed his servants and entered the Temple of Serapis, alone, to consult the auspices and discover how long he would last as Emperor. After many propitiatory sacrifices he turned to go, but was granted a vision of his freedman Basilides handing him the customary branches, garlands, and bread — although Basilides had for a long time been nearly crippled by rheumatism and was, moreover, far away. Almost at once dispatches from Italy brought the news of Vitellius's defeat at Cremona, and his assassination at Rome.

Vespasian, still rather bewildered in his new role of Emperor, felt a certain lack of authority and of what might be called the divine spark; yet both these attributes were granted him. As he sat on the Tribunal, two labourers, one blind, the other lame, approached together, begging to be healed. Apparently the god Serapis had promised them in a dream that if Vespasian would consent to spit in the blind man's eyes, and touch the lame man's leg with his heel, both would be made well. Vespasian had so little faith in his curative powers that he showed great reluctance in doing as he was asked; but his friends persuaded him to try them, in the presence of a large audience, too — and the charm worked. At the same time, certain soothsayers were inspired to excavate a sacred site at Tegea in Arcadia, where a hoard of very ancient vases was discovered, all painted with a striking likeness of Vespasian.

8. As a man of great promise and reputation — he had now been decreed a triumph over the Jews — Vespasian found no difficulty, on his return to Rome, in adding eight more consulships to the one he had already earned. He also assumed the office of Censor, and throughout his reign made it his principal business to shore up the moral foundations of the State, which were in a state of collapse, before proceeding to its artistic embellishment. The troops, whose discipline had been weakened either by the exultation of victory or by the humiliation of defeat, had been indulging in all sorts of wild excesses; and rumbles of internal dissension could be heard in the provinces and free cities, as well as in certain of the petty kingdoms. This led Vespasian to discharge or punish a large number of Vitellius's men and, so far from showing them any special favour, he was slow in paying them even the victory bonus to which they were entitled. He missed no opportunity of tightening discipline: when a young man, reeking of perfume, came to thank him for a promotion in rank, Vespasian turned his head away in disgust and cancelled the order, saying crushingly: 'I should not have minded so much if it had been garlic.' When the marine fire brigade, detachments of which had to be constantly on the move between Ostia or Puteoli and Rome, applied for a special shoe allowance, Vespasian not only turned down the application, but instructed them in future to march barefoot; which has been their practice ever since.

He reduced the free states of Achaea, Lycia, Rhodes, Byzantium, and Samos, and the kingdom of Trachian Cilicia and Commagene, to provincial status. He garrisoned Cappadocia as a precaution against the frequent barbarian raids, and appointed a governor-general of consular rank instead of a mere knight.

In Rome, Vespasian authorized anyone who pleased to take over the sites of ruined or destroyed houses, and build on them if the original owners failed to come forward. He personally inaugurated the restoration of the burned Capitol by collecting the first basketful of rubble and carrying it away on his shoulders; and undertook to replace the 3,000 bronze tablets which had been lost in the fire, hunting high and low for copies of the inscriptions engraved on them. Those ancient, beautifully phrased records of senatorial decrees and popular ordinances dealt with such matters as alliances, treaties, and the privileges granted to individuals, and dated back almost to the foundation of Rome.

9. He also started work on several new buildings: a temple of Peace near the Forum, a temple to Claudius the God on the Caelian Hill, begun by Agrippina but almost completely destroyed by Nero; and the Colosseum, or Flavian Amphitheatre, in the centre of the City, this having been a favourite project of Augustus's.

He reformed the Senatorial and Equestrian Orders, now weakened by frequent murders and continuous neglect; replacing undesirable members with the most eligible Italian and provincial candidates available; and, to define clearly the difference between these Orders as one of status rather than of privilege, he pronounced the following judgement in a dispute between a senator and a knight: 'No abuse must be offered a senator; it may only be returned when given.'

10. Vespasian found a huge waiting list of law-suits: old ones left undecided because of interruptions in regular court proceedings, and new ones due to the recent states of emergency. So he drew lots for a board of commissioners to settle war compensation claims and make emergency decisions in the Centumviral Court, thus greatly reducing the number of cases. Most of the litigants would otherwise have been dead by the time they were summoned to appear.

11. Since nothing at all had been done to counteract the debauched and reckless style of living then in fashion, Vespasian induced the Senate to decree that any woman who had taken another person's slave as a lover should lose her freedom; and that nobody lending money to a minor should be entitled to collect the debt, even if the father died and the minor inherited the estate.

12. He was from first to last modest and restrained in his conduct of affairs, and more inclined to parade, than to cast a veil over, his humble origins. Indeed, when a group of antiquaries tried to connect his ancestors with the founders of Reiti, and with one of Hercules's comrades whose tomb is still to be seen on the Salarian Way, Vespasian burst into a roar of laughter. He had anything but a craving for outward show; on the day of his triumph the painful crawl of the procession so wearied him that he said frankly:

'What an old fool I was to demand a triumph, as though I owed this honour to my ancestors or had ever made it one of my own ambitions! It serves me right!'

Moreover, he neither claimed the tribunicial power of vetoing the Senate's acts nor adopted the title 'Father of the Country' until very late in his life; and even before the Civil War was over, discontinued the practice of having everyone who attended his morning audiences' searched for concealed weapons.

13. Vespasian showed great patience if his friends took liberties with him in conversation, or lawyers made innuendoes in their speeches, or philosophers affected to despise him; and great restraint in his dealings with Licinius Mucianus, a bumptious and immoral fellow who traded on his past services, in the matter of the Syrian legions, by treating him disrespectfully. Thus, he complained only once about Mucianus, and then in private to a common acquaintance, his concluding words being: 'I at least am a man.' When Salvius Liberalis was defending a rich client he earned a pat on the back from Vespasian by daring to ask:

'Does the Emperor really care whether Hipparchus is, or is not, worth a million in gold?'

And when Demetrius the Cynic, who had been banished from Rome, happened to meet Vespasian's travelling party, yet made no move to rise or salute him, and barked out some rude remark or other, Vespasian merely commented: 'Good dog!'

14. Not being the sort of man to bear grudges or pay off old scores, he arranged a splendid match for the daughter of his former enemy Vitellius, even providing her dowry and trousseau. Then there was the matter of the chief usher. When, long before, Vespasian had been dismissed from Nero's Court, and cried in terror: 'But what shall I do? Where on earth shall I go?' the chief usher answered: 'Oh, go to Plagueville!' and pushed him out of the Palace. He now came to beg for forgiveness, and Vespasian did no more than show him the door with an equally short and almost identically framed good-bye. He felt so little inclination to execute anyone whom he feared or suspected that, warned by his friends against Mettius Pompusianus, who was believed to have an Imperial horoscope, he saddled him with a debt of gratitude by making him Consul.

15. My researches show that no innocent party was ever punished during Vespasian's reign except behind his back or while he was absent from Rome, unless by deliberate defiance of his wishes or by misinforming him about the facts in the case. He showed great leniency towards Helvidius Priscus who, on his return from Syria, was the only man to greet him as 'Vespasian' instead of 'Caesar'; and who, throughout his praetorship, omitted all courteous mention of him from official orders. However, feeling himself, as it were, reduced to the ranks by Priscus's insufferable rudeness, Vespasian flared up at last, banished him and presently gave orders for his execution. Nevertheless, he meant to save him, and wrote out a reprieve; but this was not delivered, owing to a mistaken report that Priscus had already been executed. Vespasian never rejoiced in anyone's death, and would often weep when convicted criminals were forced to pay the extreme penalty.

16. His one serious failing was avarice. Not content with restoring the duties remitted by Galba he levied new and heavier ones; increased, and sometimes doubled, the tribute due from the provinces; and openly engaged in business dealings which would have disgraced even a private citizen — such as cornering the stocks of certain commodities and then putting them back on the market at inflated prices. He thought nothing of exacting fees from candidates for public office, or of selling pardons to the innocent and guilty alike; and is said to have deliberately raised his greediest procurators to positions in which they could fatten their purses satisfactorily before he came down hard on them for extortion. They were, at any rate, nicknamed his sponges — he put them in to soak, only to squeeze them dry later.

Some claim that greed was in Vespasian's very bones — an accusation once thrown at him by an old slave of his, a cattleman. When Vespasian became Emperor the slave begged to be freed but, finding that he was expected to buy the privilege, complained: 'So the fox has changed his fur, but not his nature!' Still, the more credible view is that the emptiness alike of the Treasury and the Privy Purse forced Vespasian into heavy taxation and unethical business dealings; he himself had declared at his accession that 400,000,000 gold pieces were needed to put the country on its feet again. Certainly he spent his income to the best possible advantage, however questionable its sources.

17. Vespasian behaved most generously to all classes: granting subventions to senators who did not possess the property qualifications of their rank; securing impoverished ex-Consuls an annual pension of 5,000 gold pieces; rebuilding on a grander scale than before the many cities throughout the Empire which had been burned or destroyed by earthquakes; and proving himself a devoted patron of the arts and sciences.

18. He first paid teachers of Latin and Greek rhetoric a regular annual salary of 1,000 gold pieces from the Privy Purse; he also awarded prizes to leading poets, and to artists as well, notably the restorers of the Venus of Cos and the Colossus. An engineer offered to haul some huge columns up to the Capitol at moderate expense by a simple mechanical contrivance, but Vespasian declined his services:

'I must always ensure,' he said, 'that the working classes earn enough money to buy themselves food.'

Nevertheless, he paid the engineer a very handsome fee.

19. When the Theatre of Marcellus opened again after Vespasian had built its new stage, he revived the former musical performances and presented Apelles the tragic actor with 4,000 gold pieces; Terpnus and Diodorus the lyre-players, with 2,000 each; and several others with 1,000. His lowest cash awards were 400. But he also distributed several gold crowns. Moreover, he ordered a great number of formal dinners on a lavish scale, to encourage the victualling trade. On 23 December, the Saturnalian Festival, he gave special gifts to his male dinner guests, and did the same for women on 1 March, which was Matrons' Day. But even this generosity could not rid him of his reputation for stinginess. Thus the people of Alexandria continued to call him 'Cybiosactes' ('a dealer in small cubes of fish'), after one of the meanest of all their kings. And when he died, the famous comedian Favor, who had been chosen to wear his funeral mask in the procession and give the customary imitations of his gestures and words, shouted to the procurators:

'Hey! how much will all this cost?' 'A hundred thousand,' they answered. 'Then I'll take a thousand down, and you can just pitch me into the Tiber.'

20. Vespasian was square-shouldered, with strong, well-formed limbs, but always wore a strained expression on his face; so that once, when he asked a well-known wit who always used to make jokes about people: 'Why not make one about me?' the answer came: 'I will, when you have at last finished relieving yourself.' He enjoyed perfect health and took no medical precautions for preserving it, except to have his throat and body massaged regularly in the ball-alley, and to fast one whole day every month.

21. Here follows a general description of his habits. After becoming Emperor he would rise early, before daylight even, to deal with his private correspondence and official reports. Next, he would invite his friends to wish him good-morning while he put on his shoes and dressed for the day. Having attended to any urgent business he would first take a drive and then return to bed for a nap — with one of the several mistresses whom he had engaged after Caenis's death. Finally, he took a bath and went to dinner, where he would be in such a cheerful mood that members of his household usually chose this time to ask favours of him.

22. Yet Vespasian was nearly always just as good-natured, cracking frequent jokes; and, though he had a low form of humour and often used obscene expressions, some of his sayings are still remembered. Taken to task by Mestrius Florus, an ex-consul, for vulgarly saying plostra instead of plaustra (waggons), he greeted him the following day as 'Flaurus'. Once a woman complained that she was desperately in love with him, and would not leave him alone until he consented to seduce her. 'How shall I enter that item in your expense ledger?' asked his accountant later, on learning that she had got 4,000 gold pieces out of him. 'Oh,' said Vespasian, 'just put it down to "love for Vespasian".'

23. With his knack of apt quotation from the Greek Classics, he once described a very tall man whose genitals were grotesquely over-developed as:

' Striding along with a lance which casts a preposterous shadow,'

— a line out of the Iliad. And when, to avoid paying death duties into the Privy Purse, a very rich freedman changed his name and announced that he had been born free, Vespasian quoted Menander's:

O, Laches, when your life is o'er,

Cerylus you will be once more.

Most of his humour, however, centred on the way he did business; he always tried to make his swindles sound less offensive by passing them off as jokes. One of his favourite servants applied for a stewardship on behalf of a man whose brother he claimed to be. 'Wait,' Vespasian told him, and had the candidate brought in for a private interview. 'How much commission would you have paid my servant?' he asked. The man mentioned a sum. 'You may pay it directly to me,' said Vespasian, giving him the stewardship. When the servant brought the matter up again, Vespasian's advice was: 'Go and find another brother. The one you mistook for your own turns out to be mine !'

Once, on a journey, his muleteer dismounted and began shoeing the mules; Vespasian suspected a ruse to hold him up, because a friend of the muleteer's had appeared and was now busily discussing a law-suit. Vespasian made the muleteer tell him just what his shoeing fee would be; and insisted on being paid half. Titus complained of the tax which Vespasian had imposed on the contents of the City urinals (used by the fullers to clean woollens). Vespasian handed him a coin which had been part of the first day's proceeds: 'Does it smell bad, my son?' he asked. 'No, Father!' 'That's odd: it comes straight from the urinal! When a deputation from the Senate reported that a huge and expensive statue had been voted him at public expense, Vespasian held out his hand, with: 'The pedestal is waiting.'

Nothing could stop this flow of humour, even the fear of imminent death. Among the many portents of his end was a yawning crevice in Augustus's Mausoleum. 'That will be for Junia Calvina,' he said, 'she is one of his descendants.' And at the fatal sight of a comet he cried: 'Look at that long hair! The King of Parthia must be going to die.' His death-bed joke was: 'Dear me! I must be turning into a god.'

24. During his ninth and last consulship Vespasian visited Campania, and caught undulant fever, though it was not a serious attack. He hurried back to Rome, then went on to Cutilae and his summer retreat near Reiti, where he made things worse by bathing in cold water and getting a stomach chill. Yet he carried on with his Imperial duties as usual, and even received deputations at his bedside; until he almost fainted after a sudden violent bout of diarrhoea, struggled to rise, muttering that an Emperor ought to die at least on his feet, and collapsed in the arms of the attendants who went to his rescue. This was 23 June 79 A.D. and he had lived sixty-nine years, seven months, and seven days.

25. All accounts agree on Vespasian's supreme confidence in his horoscopes and those of his family. Despite frequent plots to murder him, he dared tell the Senate that either his sons would succeed him or there would be no more Roman Emperors. He is said to have dreamed about a pair of scales hanging in the Hall of the Palace: Claudius and his adopted son Nero, in one pan, were exactly balanced against himself, Titus and Domitian in the other. And this proved an accurate prophecy, since the families were destined to rule for an equal length of time.