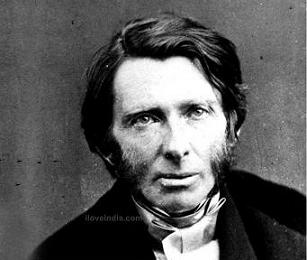

John Ruskin was born on 8 February 1819 at 54 Hunter Street, London, the only child of Margaret and John James Ruskin. His father, a prosperous, self-made man who was a founding partner of Pedro Domecq Sherries, collected art and encouraged his son's literary activities, while his mother, a devout evangelical Protestant, early dedicated her son to the service of God and devoutly wished him to become an Anglican bishop. Ruskin, who received his education at home until the age of twelve, rarely associated with other children and had few toys. During his sixth year he accompanied his parents on the first of many annual tours of the Continent. Encouraged by his father, he published his first poem, 'On Skiddaw and Derwent Water', at the age of eleven, and four years later his first prose work, an article on the waters of the Rhine.

In 1836, the year he matriculated as a gentleman-commoner at Christ Church, Oxford, he wrote a pamphlet defending the painter Turner against the periodical critics, but at the artist's request he did not publish it. While at Oxford (where his mother had accompanied him) Ruskin associated largely with a wealthy and often rowdy set but continued to publish poetry and criticism; and in 1839 he won the Oxford Newdigate Prize for poetry. The next year, however, suspected consumption led him to interrupt his studies and travel, and he did not receive his degree until 1842, when he abandoned the idea of entering the ministry. This same year he began the first volume of Modern Painters after reviewers of the annual Royal Academy exhibition had again savagely treated Turner's works, and in 1846, after making his first trip abroad without his parents, he published the second volume, which discussed his theories of beauty and imagination within the context of figural as well as landscape painting.

On 10 April 1848 Ruskin married Euphemia Chalmers Gray, and the next year he published The Seven Lamps of Architecture, after which he and Effie set out for Venice. In 1850 he published The King of the Golden River, which he had written for Effie nine years before, and a volume of poetry, and in the following year, during which Turner died and Ruskin made the acquaintance of the Pre-Raphaelites, the first volume of The Stones of Venice. The final two volumes appeared in 1853, the summer of which saw Millais, Ruskin, and Effie together in Scotland, where the artist painted Ruskin's portrait. The next year his wife left him and had their marriage annulled on grounds of non-consummation, after which she later married Millais. During this difficult year, Ruskin defended the Pre-Raphaelites, became close to Rossetti, and taught at the Working Men's College.

In 1855 Ruskin began Academy Notes, his reviews of the annual exhibition, and the following year, in the course of which he became acquainted with the man who later became his close friend, the American Charles Eliot Norton, he published the third and fourth volumes of Modem Painters and The Harbours of England. He continued his immense productivity during the next four years, producing The Elements of Drawing and The Political Economy of Art in 1857, The Elements of Perspective and The Two Paths in 1859, and the fifth volume of Modern Painters and the periodical version of Unto This Last in 1860. During 1858, in the midst of this productive period, Ruskin decisively abandoned the evangelical Protestantism which had so shaped his ideas and attitudes, and he also met Rose La Touche, a young Irish Protestant girl with whom he was later to fall deeply and tragically in love.

Throughout the 1860s Ruskin continued writing and lecturing on social and political economy, art, and myth, and during this decade he produced the Fraser's Magazine 'Essays on Political Economy' (1862-3; revised as Munera Pulveris, 1872), Sesame and Lilies (1865), The Crown of Wild Olive (1866), The Ethics of the Dust (1866), Time and Tide, and The Queen of the Air (1869), his study of Greek myth. The next decade, which begins with his delivery of the inaugural lecture at oxford as Slade Professor of Fine Art in February 1870, saw the beginning of Fors Clavigera, a series of letters to the working men of England, and various works on art and popularized science. His father had died in 1864 and his mother in 1871 at the age of ninety. In 1875 Rose la Touche died insane, and three years later Ruskin suffered his first attack of mental illness and was unable to testify during the Whistler trial when the artist sued him for libel. In 1880 Ruskin resigned his Oxford Professorship, suffering further attacks of madness in 1881 and 1882; but after his recovery he was re-elected to the Slade Professorship in 1883 and delivered the lectures later published as The Art of England (1884). In 1885 he began Praeterita, his autobiography, which appeared intermittently in parts until 1889, but he became increasingly ill, and Joanna Severn, his cousin and heir, had to bring him home from an 1888 trip to the Continent. He died of influenza on 20 January 1900 at Brantwood, his home near Coniston Water.