HE was one of those men, quos vituperate ne inimici quidem possunt, nisi ut simul laudent;... for he could never have done half that mischief without great parts of Courage, Industry, and Judgement. He must have had a wonderful understanding in the natures and humours of men, and as great a dexterity in applying them; who, from a private and obscure birth (though of a good family) without interest or estate, alliance or friendship, could raise himself to such a height, and compound and knead such opposite and contradictory tempers, humours, and interests into a consistence, that contributed to his designs, and to their own destruction; whilst himself grew insensibly powerful enough to cut off those by whom he had climbed, in the instant that they projected to demolish their own building. What was said of Cinna may very justly be said of him,

ausum eum, quae nemo auderet bonus: perfecisse, quae a nullo, nisi fortissitno perfici possunt.. .

Without doubt, no man with more wickedness ever attempted any thing, or brought to pass what he desired more wickedly, more in the face and contempt of Religion, and moral Honesty; yet wickedness as great as his could never have accomplished those designs, without the assistance of a great spirit, an admirable circumspection, and sagacity, and a most magnanimous resolution.

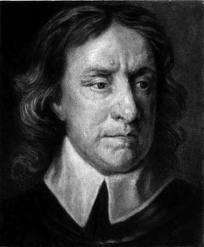

When he appeared first in the parliament, he seemed to have a person in no degree gracious, no ornament of discourse, none of those talents which use to conciliate the affections of the stander by: yet as he grew into place and authority, his parts seemed to be raised, as if he had concealed faculties, till he had occasion to use them; and when he was to act the part of a great man, he did it without any indecency, notwithstanding the want of custom.

After he was confirmed and invested Protector by the humble Petition and Advice, he consulted with very few upon any action of importance, nor communicated any enterprise he resolved upon, with more than those who were to have principal parts in the execution of it; nor with them sooner than was absolutely necessary. What he once resolved, in which he was not rash, he would not be dissuaded from, nor endure any contradiction of his power and authority; but extorted obedience from them who were not willing to yield it.

[He] was not so far a Man of blood, as to follow Machiavel's method; which prescribes upon a total alteration of Government, as a thing absolutely necessary, to cut off all the heads of those, and extirpate their families, who are friends to the old one. It was confidently reported that, in the Council of Officers, it was more than once proposed, 'that there might be a general massacre of all the Royal Party, as the only expedient to secure the government', but that Cromwell would never consent to it; it may be, out of too much contempt of his enemies. In a word, as he was guilty of many crimes against which damnation is denounced, and for which Hell-fire is prepared, so he had some good qualities which have caused the memory of some men in all ages to be celebrated; and he will be looked upon by posterity as a brave wicked man.