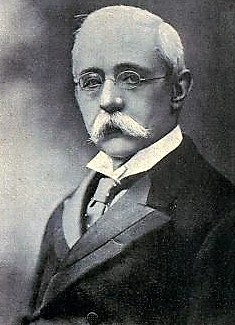

HERBERT ALLEN GILES was born in Oxford on 18th December 1845, the fourth son of John Allen Giles (1808-1884), an Anglican clergyman and Fellow of Corpus Christi College. His father had doctrinal differences with the Church and served a term in prison for a minor infraction of ecclesiastical law. As a consequence, he was obliged to make ends meet with his pen, producing a stream of publications, many of a decidedly utilitarian nature, such as a series of "cribs" of Greek and Latin texts for schoolboys. It was as a contributor to the latter that Herbert Giles made his earliest foray into the world of letters. His later agnosticism and anti-clericalism no doubt had their origins in his father's ordeal at the hands of the Church of England.

After four years at Charterhouse, Giles did not, as might have been expected, proceed to Oxford, but went instead to Peking, having passed the competitive examination for a Student Interpretership in China.

Giles' failure to rise high in the Service is to a great extent attributable to his distinctly "undiplomatic" personality. He did not "suffer fools gladly", and expressed in print views on controversial matters that were at variance with official policy and received opinion at home. He also became embroiled in a number of diplomatic contretemps, which resulted in his transferral and no doubt blighted his career. Fortunately, however, he had time and abundant energy to devote to Chinese research and publication, with the result that when he retired on health grounds (at the age of 47) after 25 years' service he had established a reputation as a sinologist which enabled him, despite his lack of formal qualifications, to advance to one of the most prestigious academic posts in Chinese studies. The Chair of Chinese at Cambridge had been vacant since the death in 1895 of its first incumbent, Giles' old chief and enemy Sir Thomas Wade, who had been appointed shortly after the gift of his collection of Chinese books to the University Library. Giles was unanimously elected on 3rd December 1897.

There were no other sinologists at Cambridge and his students were very few; indeed not until 1903 was Chinese fully recognised as a subject fit for the Tripos examination. Giles was therefore free to spend his time amongst the Chinese books presented by Wade, of which he became Honorary Keeper, publishing what he gleaned from his wide reading. He finally retired in 1932 and died, in his ninetieth year, on 13th February 1935.

Giles' published legacy may be divided into four broad categories: reference works, language textbooks, translations and miscellaneous writings. He tells us that of all his publications he was most proud of his Chinese-English Dictionary (1892; 2nd ed. 1912) and Chinese Biographical Dictionary (1898). Today the Dictionary is most often cited as the locus classicus of the so-called "Wade-Giles" romanisation system, for which the name of Giles is widely known even to non-specialists. The language textbooks are today of purely antiquarian interest.

Giles' translations are of the most catholic nature, ranging from San zi jing (1900; 2nd ed. 1910) through Fo guo ji (1877; 2nd ed. 1923) to Zhuang-zi (1889; 2nd ed. 1926) and Xi yuan lu (1924). Probably the best known today are the anthologies of prose and verse Gems of Chinese Literature (1884; 2nd ed. 1922) and Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (1878; 3rd ed. 1916), still the largest collection of stories from Liao zhai zhi yi available in English. His insistence on retaining rhyme in his verse translations, though sound in theory, gives them nowadays an antiquated flavour. In his prose translations he sometimes glosses over a difficulty by simple omission, without notifying the reader, but his style is fluent and robust, and has worn better than his verse.

Giles was notorious as a merciless critic of the work of fellow toilers in sinology, and in his journalistic writing, for which there was a ready outlet in the flourishing English-language press in China, he took delight in excoriating others for their mistranslations. Paradoxically, it is this miscellaneous and "ephemeral" writing which now seems most likely to have permanent value and interest. An example is Chinese Sketches (1876), containing observations based on nine years' residence in China on such varied topics as dentristry, etiquette, gambling, pawnbrokers, slang, superstitions and torture.

As a polemicist, Giles expressed particularly strong views on female infanticide in China (which he disbelieved), opium addiction (which he deemed preferable to alcoholism), and missionary work in China (which he considered undesirable and unnecessary). The expression of such opinions naturally made him many enemies, but once seized of a conviction he refused to change his mind. This applied to small matters as well as great; an example is his heated argument with James Legge on the authenticity of the Lao-zi, in the pages of the China Review.

Giles was a complex and contradictory personality. Ruthless with his pen, he was the soul of kindness to a friend in need. He dedicated the third edition of Strange Stories (1916) to his seven grandchildren, but at the end of his life was on speaking terms with only one of his surviving children. An ardent agnostic, he was at the same time an enthusiastic freemason. He was by all accounts a convivial companion and clubman, but never became a Fellow of his College, despite holding a Professorship for 35 years. Notwithstanding his reputation for abrasiveness, he would speak to anyone in the street "from the Vice-Chancellor to a crossing-sweeper", and was remembered by acquaintances as a man of great personal charm.